Marti Fernando De Souza, 39, Deputy Chief Education Officer with responsibility for Amerindian and Hinterland Education Development, is working to eliminate the disparity that exists in the education system between the hinterland and the coastland, create opportunities for trained and qualified teachers to teach, and to improve pass rates in examinations in hinterland areas.

At the end of 2020, the Ministry of Education (MoE) saw the need for someone who can relate to the hinterland and work on policies at the ministry level to bring the standard of education in the hinterland to a level that is on par with the coastland. As a result, the ministry created the post of DCEO for Amerindian and Hinterland Education Development and offered it to De Souza.

“It is challenging but that is what I am made for, to overcome the challenges. What really resonates with me is when I visit hinterland communities and I see the needs out there. I know I can make a difference and I know if I can’t do it, I can advocate. I can speak to people and together we can make a difference.”

De Souza who comes from Santa Rosa Village, Moruca, Region One, told Stabroek Weekend, “It doesn’t matter which secondary school you attend. If a child from Queen’s College in Georgetown can do it, any child attending secondary schools in the hinterland, whether it is Annai, Mahdia or Port Kaituma, can do it. It is just a matter of putting yourself to the task and working hard. Working hard is an integral part of success.”

He attended Santa Rosa Primary School, where he learned to love reading, which he credits for his quest for knowledge and knowledge-sharing. Prior to writing the Secondary School Entrance Examination, he suffered from ill health and missed classes in the run up to the assessments. After a period of post-surgery hospitalization, he recovered but according to him he stayed away from sports and physical activities but made up for those in the arts.

He paints, sings, and plays the guitar, ukulele, harmonica and recorder. His father, uncle and paternal grandfather were all versatile on the guitar. “My grandfather also played the violin. So it is in our DNA.”

As a child, he fished on weekends and would often paddle for hours in the creeks. “Mix it with swimming and being with nature, it was really enjoyable. I think that is what got me so involved in the environment. Preserving the environment was something that was engrained in me from a very young age.”

From his early teens, De Souza was very active in youth development and organizing social activities, like summer camps, for his peers. While he was a student at Santa Rosa Secondary School (SRSS), he was also the president of the Santa Rosa Environmental Club. In 1998, he was a youth parliamentarian and he called it “an important time” in his life.

His father, former PPP/C MP Joseph Marco De Souza, was a parliamentarian and was in the chamber and he credits him with influencing him in activism. “I admired how he carried himself in his world of politics. That influenced me. It might not have influenced me in heading down the political road but what stuck with me was his attitude in wanting to make a change and I wanted to make a change. He wasn’t afraid to speak. I looked at him on the political platform and the way he articulated. What I wanted to do was not to represent one set of people but to serve everyone, regardless of their political background.”

Because of his youth activism, when he was 14 years he was recognised with an award by the Regional Democratic Council, Region One. “That was a motivation for me as a youth activist. As a youth ambassador, many of the conferences focused on teens and what was happening at the time. For example, in the preparation for the Commonwealth Heads of Government meetings we looked at the issues such as youth unemployment, scholarships and including young people in decision-making. “These were issues we shared with the heads.”

A teenage teaching career

In 1999, at just 15 years, after writing the Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate (CSEC) at SRSS, he took on the job of integrated science teacher to teach children who were sometimes older than himself.

“I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do career wise. I taught for a year. After that year when I got the CSEC results and my class achieved 100 per cent passes at integrated science, I was motivated. I wanted to be a trained teacher. In 2000 I started the three-year secondary training programme at Cyril Potter College of Education (CPCE).

During his first year at CPCE, he was nominated Guyana’s Regional Youth Caucus (RYC) representative to the Commonwealth Caribbean.

“In that position, I met with fellow Caribbean and Commonwealth youth ambassadors. I attended many international forums in different countries. I met with some heads of states, including Jamaica’s then Prime Minister PJ Patterson and Suriname’s then President Ronald Venetiaan.

He represented Guyana in 2001 at a UNESCO-sponsored conference for young men in Rio De Janeiro, which he said opened his eyes to a number of gender equality issues, including young men regressing in society by dropping out of school and engaging in antisocial activity. He represented Guyana at several youth forums in Australia, Malta, Mexico and in the Caribbean. “All this happened while I was at CPCE so I had to balance being a youth ambassador with my studies.”

After graduating from CPCE in 2003, he taught for a year at Lusignan Primary as he was still Guyana’s RYC representative. In 2004, he returned to teach at SRSS. In 2006, he became head of the science department.

In 2007, he was named Guyana’s Caricom Youth Ambassador for a year. “All the while I was in Moruca trying to balance my duties as a youth ambassador and my career as a teacher.” That same year, he entered the University of Guyana (UG) to read for a bachelor’s degree in education administration. “In my early days at UG, on my way to classes, I occasionally met some of my former SRSS students at UG. It was good knowing that I contributed to their entry to university and we were there together.”

At UG he passed the certificate of education with distinction, he made the Dean’s Honour Roll for academic performance during his pursuit of his bachelor’s degree and in 2011 graduated with distinction.

In his final year at UG, his mother died. “That was a blow to me. When she passed I was preparing for my final exams. However, I channeled all the negative energies, the grief and sorrow to doing what I knew she wanted me to do. I wrote my final exams a few weeks after my her funeral.”

After graduation he returned once more to SRSS. In 2012, at age 28, he took on the role as headmaster, which was initially a challenge to him because many of the teachers at the school were much older than him.

“I wanted to make a difference but I had to convince teachers who were older than me that we had to do things differently. I knew that I was not going to be there forever and I wanted to leave the school better than I found it. With a lot of planning, organizing and motivating, I was able to incrementally see progress. I had a very vibrant parent teachers’ association. I had the support of the community and we did many things for the school.”

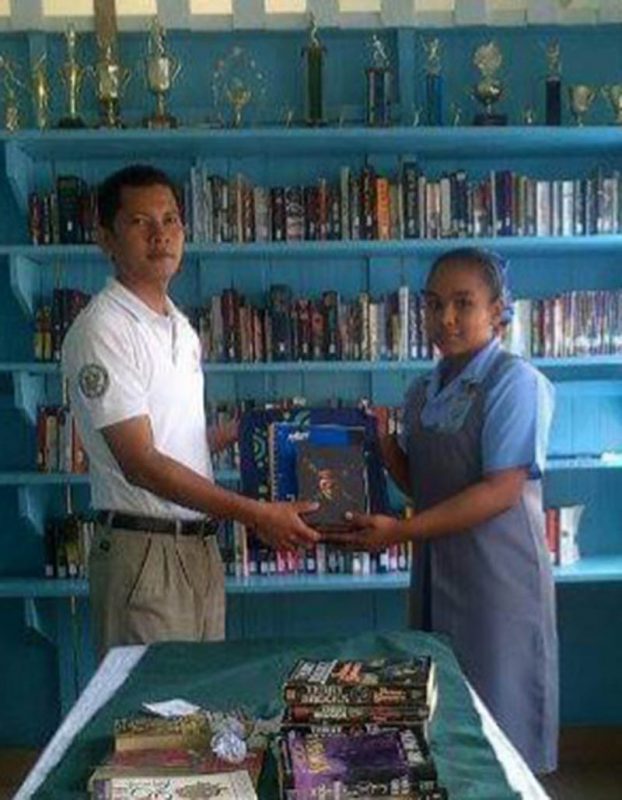

He also reached beyond the community by networking with interest groups in Canada to start a library. The school had the space for the library. He shared his idea of the library on Facebook and the response was networking with groups out of Canada who assisted in stocking the library.

He also promoted staff development sessions, including using staff members who were adept at information technology to share their knowledge with their colleagues. “That was a way I tried to get them to grow professionally.”

The biggest reward

In 2015, the Region One Department of Education recommended that De Souza join the MoE’s two-year cadet programme that trains people within the education stream to become education officers.

“When I was leaving the school on the cadet programme, I told my students my biggest reward would be their results. That same year, a number of students did really well. Three of them, each achieved ten grades ones. It was a first for SRSS. There was my reward. Even though it was a team effort, I think my leadership counted. I can look back with pride on those results.”

In 2017, on completion of the cadet programme, De Souza was appointed an education officer in Region One and was based at Mabaruma. “I was working with Nigel Richards, who was headmaster of SRSS when I was a student there and he was a mentor to me as a teacher. “I was serving with my mentor.”

In 2017, he also represented Guyana in China on a one-month programme for education officers in developing countries at the University of Jilin in China.

“During my tenure as education officer I worked with the head teachers in the Mabaruma sub-region to see how we could improve and get things moving. I was working quite well with the head teachers when the Covid-19 pandemic struck. At the end of 2019 and into 2020, we knew we were going to go into a lockdown. As education officers we started working with schools to produce worksheets and to connect them through the local radio station in Mabaruma. The pandemic was compounded with the 2020 elections’ fiasco. Not much was happening. We produced work sheets at our level and we tried as best as possible to broadcast education programmes on the radio.”

De Souza was coordinator and a radio broadcaster for Radio Mabaruma from 2017 to 2019 “merging education with entertainment into ‘edutainment, a popular morning broadcast.”

With the help of the regional administration, he got a radio for every home that had a school child in Powaikuro, a small Warrau settlement off the Kaituma River. “We broadcasted our educational content on Radio Mabaruma. That was one of the initiatives I tried to keep children engaged at that time.”

As education officer in 2017, he said, “We were toying with the idea of virtual learning in the hinterland. We had a teacher do a class online and we had an audience. We knew that virtual learning was possible. So even before the pandemic and this drive to virtual learning, I knew to myself that in the hinterland, once we have connectivity and there is good internet we can actually bring specialist teachers into the classroom and the children wherever they are, and wherever there is connectivity, can benefit from it.”

In his capacity as DCEO, he brought together 12 hinterland schools and a number of primary tops for online classes. Internet connectivity remains a problem.

Looking back at his tenure as an administrator, he said, “I hadn’t much resistance because I had faith in my leadership style. I think I can empathise and relate to people so no matter the circumstance I found myself in, there were not many conflicts.”

He recalled when he was at Mabaruma, there was one senior administrator who thought De Souza was not fit for the position of education officer because of his age. “Even then I did what I had to do and to the best of my ability. Even though the individual might not have liked me personally, that did not come between my line of work and at no time did I compromise my work because someone felt I was not good enough for the job. I continued to be me. I survived and today I am who I am.”