Assassins of conversation

they bury the voice

they assassinate, in the beloved

grave of the voice, never to be silent.

I sit in the presence of rain

in the sky’s wild noise

of the feet of some who

not only, but also, kill

the origin of rain, the ankle

of the whore, as fastidious

as the great fight, the wife

of water. Risker, risk.

I intend to turn a sky

of tears, for you

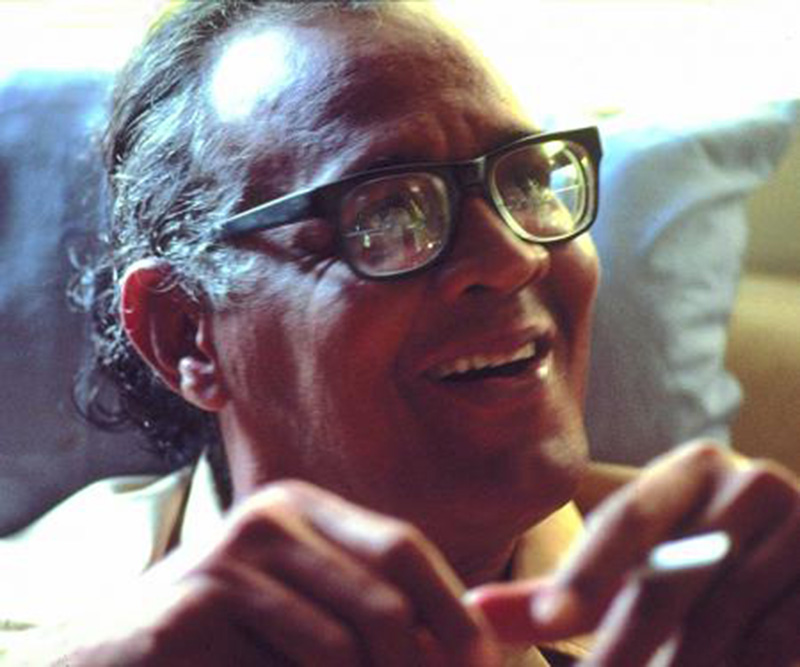

– Martin Carter

Martin Carter’s Diaries

28/10/63

“The alchemists sought to find the philosopher’s stone which would transmute base metals into gold. Guyanese society contains that which transmutes anything of value into base matter.

I say that to be a writer is to have a profession: to be a poet is to have a way of life. What, now, is the poet’s way of life? I think it consists of always continuously making use of the raw material of experience to sponsor the essential human truth. But what is human truth? That which is perceived in a dialectical instant? That stage is a process when time is abolished and birth or rebirth can take place.

Thus, the way of life of a poet is always to be ready, always prepared to be available at, and for a dialectical instant. Here, of course since all experience is subjective, dialectical instances occur privately. Further at a dialectical instant there must occur a leap: from becoming this state of being consisting of what I call the dialectical instant. Thus from becoming to being to becoming ad infinitum.”

Extracts selected by Phyllis Carter and Sonia Carter-Dolphin

Pablo Neruda

“On the back page of this issue is a poem by Pablo Neruda (I want the Earth). Pablo Neruda is one of the greatest living poets in the world. He is Chilean and his poems are originally written in Spanish. The version printed here is therefore a translation.

Two years ago Pablo was awarded a Stalin Prize for outstanding work in the cause of the maintenance of world peace. The award of such a prize is a tribute to Neruda’s poetic power, a tribute to his unflinching stance in defence of human culture and civilisation. It is also a tribute to the Chilean people without whom there could be no Pablo Neruda.

In his early life the poet travelled widely in the world for he worked for the diplomatic service of Chile. He served from time to time in India, Burma and other Eastern and European countries. At the time he was still dominated by the anxieties of decaying bourgeois society and his poetry was permeated by death wishes and full of all the obscurantism now so fashionable in certain literary circles in Europe and America.

It was during his period of service in Spain that he really came alive. The Spanish Civil War opened his eyes to the truth. The inhuman activities of the Fascists assisted by Hitler and Mussolini revolted him. He saw how ordinary men and women could become heroes in the fight for liberty, how down there in the thoroughfares of reality that history was being made. And from then on he heard among the marching sounds of men going forward to the dawn.

Back in Chile, Neruda joined forces with the liberation movement of the people and was elected by the tin miners to represent them in the National Assembly. But this did not last too long. Soon the police were at him like a pack of mad dogs and he was forced to flee as he himself has written ‘through the tall night, through all our life’.

Having escaped from the hands of the butchers who ruled Chile at the time, Neruda went from country to country, attending conferences, reading his poems to the world, and inspiring men with hope and courage. Today Neruda is back in Chile, or back at home once again doing his job, the job of a poet, which is to stand proudly on the side of truth and hope in a world full of ugliness and tumult and struggle.

Thunder is proud to print a poem by such a man and poet.”

– Martin Carter

Thunder Editorial, 15 January, 1955

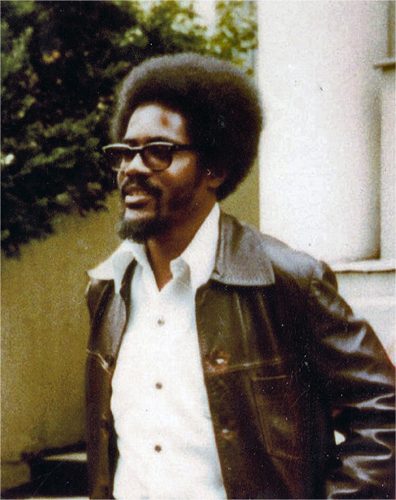

In the month of June we pay tribute to poet Martin Carter and acclaimed historian and political revolutionary Walter Rodney. Carter was born on June 7, and Rodney was assassinated on June 13. In the selections printed above, the poet offers verses in honour of the historian and a prose statement in honour of another kindred spirit – the poet, diplomat and political advocate Pablo Neruda.

The poem “For Walter Rodney” was written in 1980 following his murder, and is to be found in the collection Poems of Affinity (1981). The first prose excerpt was taken from Carter’s diaries by his wife Phyllis Carter and daughter Sonia Carter-Dolphin and published in Kyk-Over-Al 49/50, a special double issue titled “Martin Carter Tribute”, which appeared in June, 2000. The piece on Pablo Neruda is an editorial published in Thunder Vol 5 No 42, January, 1955 while Carter served as editor of that periodical.

The poem is an eloquent representative of Carter’s work, the careful precision, the delicate balance of words, yet the enigmatic subtext and the paradox that divides each line. He confronts contradictions in assassinations such as the killing of Rodney, interpreted here as an attempt to silence his voice. But the voice is impossible to bury, it is something “never to be silent” and Carter approaches it with a statement of defiance. He invokes the metaphor of rain and the natural environment, but an environment disturbed. “The sky’s wild noise” is the almost thunderous sound of falling rain, but may also be the sound of loudly squawking birds. Yet it is pathetic fallacy in the sense of a noisy protest from the sky at the violation of the natural order caused by the assassination of such a one as Rodney.

It is to that image of rain that the poem returns in its last two lines – “I intend to turn a sky/ of tears for you.” The poet will turn himself into the sky – he will become the sky in the production of rain. Interestingly, Carter falls back on the old Petrarchan conceit of “tears like rain” to express his grief; in the way he will produce tears. But he will also produce the wild noises of protest at the major disruption of the natural order when Rodney was killed. He will dispute the contrary concept of assassination.

A number of things come out in his tribute to Neruda. The organ Thunder that he edited in the 1950s was notable in its attention to poetry; several poems were published in its pages. Here it expresses pride in publishing Neruda. The editorial serves as quite a comprehensive introduction to the poem “I Want the Earth” with its instructive critical and biographical background of the poet. Prominent in this introduction are the references to politics. Neruda’s life was a liberation struggle on behalf of people, and that can be quite closely compared to the efforts of both Carter and Rodney.

Neither is this unrelated to the diary entry. Carter refers to alchemy, a mediaeval pursuit often found in literature. It is at the core of Chaucer’s “The Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale” (1387 – 1400), as well as among the Elizabethans, eg Ben Jonson’s play The Alchemist (1610) and the poetry of John Donne. Carter invokes it as a damning criticism of Guyanese society and the task facing the writer. He is consistent in his contention that poetry is a profession and poetry is a way of life, which he certainly lived.

Of interest, as well, is the (in)famous metaphor used by Rodney in his political speeches in criticism of Forbes Burnham, whose touch, he joked, turned gold into base material. And of further interest is another study of Carter which interrogates the role of the poet in his “use of the raw material to sponsor . . . human truth”. It is precisely this struggle that concerns Tessa McWatt in her writing of the libretto for “The Knife of Dawn” performed in London at the Roundhouse (2016) and the Royal Opera House (2020). It investigates Carter’s role as poet and revolutionary in the occupation of British Guiana in 1953. That was a subject often revisited by the poet himself in his poetry, and certainly in the entry from his diaries extracted and reprinted here.