Very early in her life, Amlata Persaud distinguished herself academically, topping the country at the Secondary Schools Entrance Examinations, the Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate examinations in 1999 and later at the GCE ‘A’ Levels examinations. The former Queen’s College student is also Guyana’s first female Rhodes Scholar and, perhaps, the first Guyanese to receive several prestigious fellowships of one kind.

Now Dr Amlata Persaud, she is a global education specialist, who is spearheading the leadership and systems section of Childhood Education International (CEI), doing consultancies, developing and delivering leadership training programmes and strategic planning programmes for education leaders globally.

CEI is an international development organisation, founded in 1892, that works to strengthen and amplify solutions to education challenges by supporting leaders in education systems. It focuses on improving children’s lives, with particular attention to the most vulnerable living in challenging circumstances.

“If you really want to support the child, you have to support the framework, all the things going on around them, teachers, people in ministries, non-governmental organisations, policies,” Persaud told Stabroek Weekend in a recent interview from her Tucson, Arizona, US home.

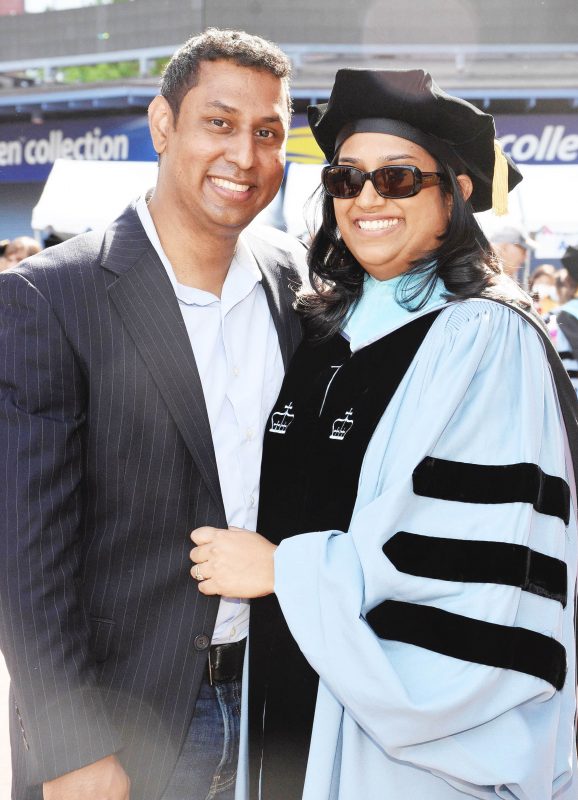

In May this year, she received the title, Doctor of Education (Ed D) in international education development from the prestigious Teachers College, Columbia University, New York. She is the holder of a Master’s in Philosophy (MPhil) in development studies, 2007, and a Bachelor of Arts (BA) graduating with honours in politics, philosophy and economics from the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Coming from a family of lawyers, Persaud, daughter of Senior Counsel Vidyanand Persaud, said, “My passion was always development, poverty reduction and helping countries to move forward. Different disciplines were more appropriate, so I started off with economics and politics. Over time those interests changed.”

At Queen’s College Persaud wrote, as one of her subjects, Law, at the General Certificate of Education (GCE) Advanced Level Examinations in 2001 to see if it interested her. “Other things were better suited to me and my family supported that.”

Family life

Now married, Persaud is the mother of a son, 5, and daughter, 3. “I have a full plate. I started my doctorate in 2013 at about the time I started my family, an extremely challenging situation. I like to think of it, not as a detour, but as a different way of life alongside academia. I took a number of leave of absences during my studies because I wanted to spend time with the children when they were younger. Then when COVID-19 hit in 2020, I was at the stage of finishing up and we kept the children at home because they were very young. They went through pre-school and I was at home with them full time, then I got back into studies. I was juggling fulltime mom, dissertation and consulting.”

She laughingly said, “It took me almost a decade working on the doctorate and starting a family. So the last ten years have been very productive in a lot of different ways.”

The doctorate was “really deep study and that was why it took me so long because I needed to have these stretches of time where I could think as I was developing my dissertation models and different things. With the two young children and these other competing things, it was difficult to find those spaces of quiet to work. That is what made this graduation so incredible.”

Of her husband, Malcolm Sears, Persaud said, “He is my intellectual equal, a great support and my number one fan. In my dissertation’s acknowledgements, I thanked him the most. When I was working on my stuff, I explained to him what I was trying to do. He helped me to think through by sketching diagrams and together we worked it out. He is a systems engineer and I am studying systems of a different kind so I was able to benefit from his expertise. We have been great partners for a very long time.”

Persaud and Sears were classmates at QC together. Sears migrated as a teenager but the two subsequently reconnected.

Politics, education

When Persaud topped the country at the Secondary Schools Entrance Examinations in 1994 at 11 years, she had told Stabroek News she was interested in politics and wanted to see a better and united Guyana. “I still remain committed to that ideal.”

In 2003, while reading for her BA, she received the Oxford Prize for the best essay in politics. Some years after obtaining her MPhil, she returned to Guyana to work and gained a better understanding of the political landscape. “Guyana is at such an interesting point in its history. Obviously given the developments in the oil sector and the opportunities and challenges that those bring, I feel like I felt when I was 11, that there is just tremendous potential in our people and our resources. The challenge continues to be how do we use those effectively and what are the best levers for change. I am trying to understand how best we can create change and what is the best way for me to work on that.”

Having completed her BA in philosophy, politics and economics, she became more interested in economics. She was trained and functioned as an economist to understand the way economies work, thinking that economics was the solution to development.

“Then I realised that was only one part of the equation of development. A lot of purely economic solutions fail. The reason is that we do not look at all the other elements that make up society. When you design a programme for intervention in a community or country, you need to look at its history, its social structure, all different things. Context matters.”

Her MPhil in development studies was a broader approach than just economics.

Since the Rhodes Scholarship in 2005, Persaud was awarded an Overseas Development Institute (ODI) Fellowship, 2007-2009; Columbia University Teachers College, Doctoral Fellowship, 2013-2016; Education Pioneers Fellowship, 2014; Columbia University Teachers College, Education Policy Dissertation Fellowship, 2017; and Columbia University Teachers College, Education Policy Dissertation Fellowship, 2022. Persaud has authored and co-authored several research papers and publications

Of her accomplishments, she said, “They are collective. Wherever I go I represent Guyana. That is one of the reasons I am sharing what I have done so far. When I think of the journey, I talk about my family and friends who were so important and supported me but there is a group of people, teachers, who have moulded me. We don’t accomplish these things on our own. Everything we are, is because of them. Very often, I think of my teachers in Guyana, some are still here and some have regrettably passed on. On my dissertation I worked with a committee of advisors, experts who were giving me their time, expertise and knowledge, helping me to grow as a scholar and as a practitioner. I have great respect and admiration for them all.”

The Malawi experience

After obtaining her MPhil, Persaud moved to Malawi, Africa in 2007, under the ODI fellowship and was placed in Malawi’s Ministry of Education. The London-based ODI sends trained economists to developing countries to work in line ministries to support the civil service.

“I was in a unique position because I was working in the civil service as a ministry’s employee in the planning department. I focused on budgeting and planning. Essentially we were responsible for putting together the ministry’s national education budget, a huge undertaking. We also developed the national plans for education and because of the nature of our work we had to consult.”

She was based in Lilongwe, the capital but frequently travelled throughout the country to meet with officials of the different school districts and found a lot of similarities and differences between Guyana and Malawi.

“From that perspective, it was a completely fascinating experience to see another country at work and to understand the challenges,” she said

“For me, working with Malawians and getting to know them have enriched me. Some who are my closest friends, are still a part of my life and they continue to shape me as I go forward. I have learned so much from them. I loved the food. Malawi is called, ‘The Warm Heart of Africa’, that much is true. In some ways they are very similar to Guyanese in terms of patriotism – at least those of us who are. I felt like I was a part of their community, a part of them. Malawi has many languages but the national languages are English and Chichewa. I learnt enough Chichewa to converse. It was important to be able to assimilate a bit, to connect and talk to people.”

She added, I was always interested in education and I had specialized in it in my Master’s Degree. Working in Malawi in education fortified my belief that in all of the things we can do to move a country forward, education is the cornerstone of development. I don’t think you can find anyone who can dispute that. If we do not create the foundation in education for our children, our countries will never prosper.”

Collaboration and systems

Back in Guyana from 2010 to 2013 Persaud worked as a senior economist and consultant with the Ministry of Finance while working closely with the Ministry of Education. “I wanted to understand education more fully. Between Malawi and Guyana, I started understanding those linkages between education and development.”

In 2013, she moved to the US and started the doctoral degree.

“I basically spent the past ten years studying education, education policy, education analysis, all the different facets of education. At the University of Columbia, I became really interested in early childhood education/early childhood development. If we think of education as the cornerstone of development, within the education sector the earliest years matter the most. Much scientific evidence, even economic evidence, is found to support this when you look at the returns of investment in young children. I have taken every course you can think about how young children learn, how they develop and how we need to support that in a country.”

In her dissertation, ‘Exploring collaboration in early national childhood systems’, she compared early childhood development between Guyana and Jamaica, which were trying to build early childhood systems. In 2017, she went to Jamaica.

She selected Jamaica because it stands out, not just in the Caribbean, but globally as a country that has understood the need for investment in the early years and the need for a holistic system looking at the child in a holistic way. “Jamaica is quite advanced in their efforts,” she said.

Persaud specialises in collaboration and systems in early childhood development.

“I have studied that extensively. I am passionate about the systems that support children, that support what we are trying to do and understanding both the people in the systems and the processes. I did extensive research with people to understand what really allows you to work well with someone else and what is challenging. We need to understand these things and address them if we are ever going to move forward.

“When you think about a child it is not just education that matters. It is education, health, social protection, nutrition and all the different elements, the people who are working on these things to support children. They are all located in different ministries, different agencies, everywhere and they need to come together to create a cohesive system. That is what I was studying because there are a lot of challenges with how do we work together.”

Jamaica created an Early Childhood Commission with an integrated strategy to support their children. “They are very advanced in terms of how they were thinking about and operationalizing early childhood development. They were a strong case for collaboration.”

She chose Guyana because it is her home country. “Guyana presented me with what I term was a pre-collaboration, pre-emergent case because we are not as formally connected in our efforts to support early childhood as Jamaica. In my research, I looked at what accounts for those differences.”

She continued, “My work draws the generalities of how one country gets to the stage of creating a commission and having an integrated approach and one country does not. I wanted to shed some light on this. You have to understand why all those things happened. History matters, politics, leadership, using the evidence, advocacy, all these things. I came up with a framework to explain it. Just because you have a formal collaboration system doesn’t mean that collaboration is not occurring in other little spaces and places. I found some good examples in Guyana.”

One advantage Guyana has, she said, is that it falls within a small-island developing state context where people know each other and have built relationships. “You can leverage these relationships to work together but other things have to be in place.”

In her role, Persaud travels extensively to many countries, including more recently, Vietnam where CEI delivered 2,000 early childhood leaders.

“They wanted to learn more about early childhood and strategic planning and so on. That is what we are doing. So anytime Guyana is interested, I would be as well. I’m working internationally but home is where I would also like to make a difference.”

In a researcher context, she knows many people who have contributed or continue to do “an incredible job” in early childhood development in Guyana. “I have not been involved as a practitioner in early education development in Guyana but I am willing to [be].”

Going forward, Persaud said, academia is a role she is also considering. “I love to teach and to mentor. That could also be a path for me in the future.”