By Neville J. Bissember

In February 1999, as the second round of negotiations on a successor Agreement to the Lome Convention advanced – the name Cotonou had not as yet been determined – the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) Group and the European Union (EU) travelled to Senegal to hold those discussions, honoring the tradition of an ACP Member State playing host to a session. Besides the EU’s intention to “balkanise” the grouping into six regional trade blocks and to dispense European Development Fund assistance differently, a priority area for them in the political dimension of the cooperation arrangement was on introducing good governance, which included addressing bribery and corruption, as an essential element.

In Dakar, the EU made a substantive presentation on how they perceived bribery and corruption impeding economic development, especially where it involved the fraudulent conversion or embezzlement of development finance. The ACP’s response was led by Mme. Marie-Elise Gbedo, the charming new Minister of Commerce from Benin who, in the presence of senior representatives from EU Member States, railed against foreign investors who came into ACP countries and committed acts of bribery of local officials in order to get their way. This had become a persistent modus operandi for many foreign businessmen.

As Minister Gbedo was slated to assume the Presidency of the ACP Council of Ministers a few months after, she took the unprecedented step of flying up to Brussels from Dakar, to meet with ACP Secretariat staff and acquaint herself with her imminent duties as President. In the end she never did, as shortly after her return home, her outspokenness got her fired!

In resisting this position of the EU to expand the political dimension of the cooperation arrangement, the ACP Group, led by some recalcitrants, raised all manner of red herrings against the inclusion of good governance, bribery and corruption within the text of the successor Agreement. In what was decidedly a foot-dragging exercise, the Group set up a Working Group on the Definition of Good Governance, which I was tasked to service, in my capacity at the time as Legal Counsel at the ACP Secretariat.

I distinctly remember the frustration of the Caribbean representative, having to attend the meetings of the Working Group, especially since the United Nations and the International Financial Institutions in Washington had already churned out internationally-accepted definitions on this concept. After dutifully recording the various positions advanced in the Working Group, in the end, I tinkered with some of the existing definitions, tweaked them a bit, and – voila! – produced a Report in which the ACP Group had crafted its own definition of Good Governance.

This exercise in futility was fortuitously for me an educative excursion into the culture of both Continental Europe and Francophone Africa as, in grappling with the ACP rule of producing official texts in the English and French languages, I discovered that there is no word in the French language which is equivalent to “bribery” in English (a bribe is often translated as un pot-de-vin, literally a pot of wine). To my shock and surprise, the concept of “bribery” in common law is subsumed under the rubric of “corruption”, and the French legal system must make do with references to “la corruption active et la corruption passive”, depending on whether the bribe or inducement is offered, or solicited. No wonder the dear lady Minister was sent packing, for she was a vocal critic of a concept not readily comprehended by her government, nor its colonial master, which is of course a powerhouse in the EU.

Thus, in what eventuated as Article 9 of the Cotonou Agreement, on political dialogue, while the word ‘bribery’ appears in the English text in paragraph 3, the reference in the French text is to ‘corruption, active et passive’. Similarly, as regards the UN Convention against Corruption, in the title of Articles 15,16, and 21, on Bribery of national public officials, Bribery of foreign public officials and officials of public international organisations, and Bribery in the private sector, the titles in the French text merely refer to ‘Corruption…’.

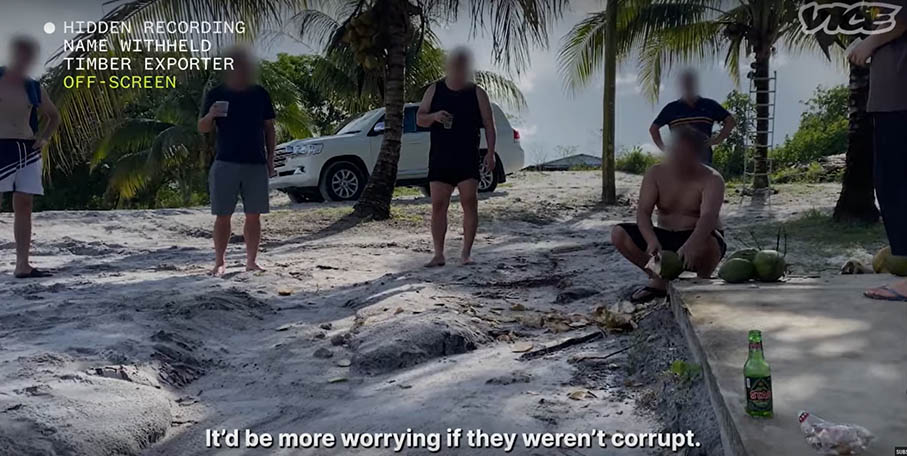

I say all of this to make the point that closer to home, there is a frenzied excitement in some quarters arising from the well-publicised Vice News story on Guyana. The response from officialdom has not been wanting: we are told ‘if people break our law and they admit to breaking our laws they should face the consequences’. Or, the administration will go ‘after investors who utilize middlemen to conduct their business in Guyana’ and will ‘…deal with these types of people, not only the people who operate like that but also the people who engage them’. For his part, the Minister responsible for law and order has referred to investigations of ‘allegations of corruption and money laundering involving Chinese nationals operating here’, although he is unsure which agency will take the lead.

Thus based on the aforesaid responses it would seem that the scope of these investigations, whenever an agency is identified, will scrutinise people who admit to breaking the law here, who utilize middlemen to conduct their business and such types of people. The scope of activity will cover Chinese nationals operating within this jurisdiction, and the subject matter will be corruption and money laundering.

So what is it that has been presented in the Vice News programme, other than reported speech and hearsay (not heresy). The programme reports on events past, without dates and specifics. Of primordial importance is the fact that while there is reference to a “bribor”, there is no credibly established “bribee”, that is to say, a recipient of any payment as an inducement, no quid pro quo, as we had learnt from Presidents Trump and Zelinski a few years ago. In the absence of a paper trail, bank deposit, or video/photo evidence – we are told of cash payments, which are usually difficult to trace – this would be an investigation going nowhere in a hurry. It may therefore seem to be the case that Stabroek News might well have been ahead of the curve in reporting on ‘allegations of money laundering and bribery schemes’. Thankfully, the French are clear on what constitutes money laundering: blanchiment d’argent.

A bribe is an inducement to do or not do something. Payment of a bribe does not necessarily amount to its receipt, in the absence of verification/corroboration. By analogy, a former superior of mine used to admonish the secretarial staff regarding email correspondence by saying, “Sending is not Receiving”. As I used to counsel my public service colleagues in the bad old days of gas shortages, you cannot bribe somebody after the fact, so a gratuity paid to a pliant pump attendant after he has afforded you preferential treatment did not constitute a bribe.

The smoking gun that is the Vice News story has left a foul odour lingering in the air, and could have a negative impact on potential investors. The administration needs therefore to find the right mix of cleansing agents to correct the situation and restore investor confidence wherever this may have been dislocated. Or could it be, perchance, that we have some francophones among us?