By Dr Bertrand Ramcharan

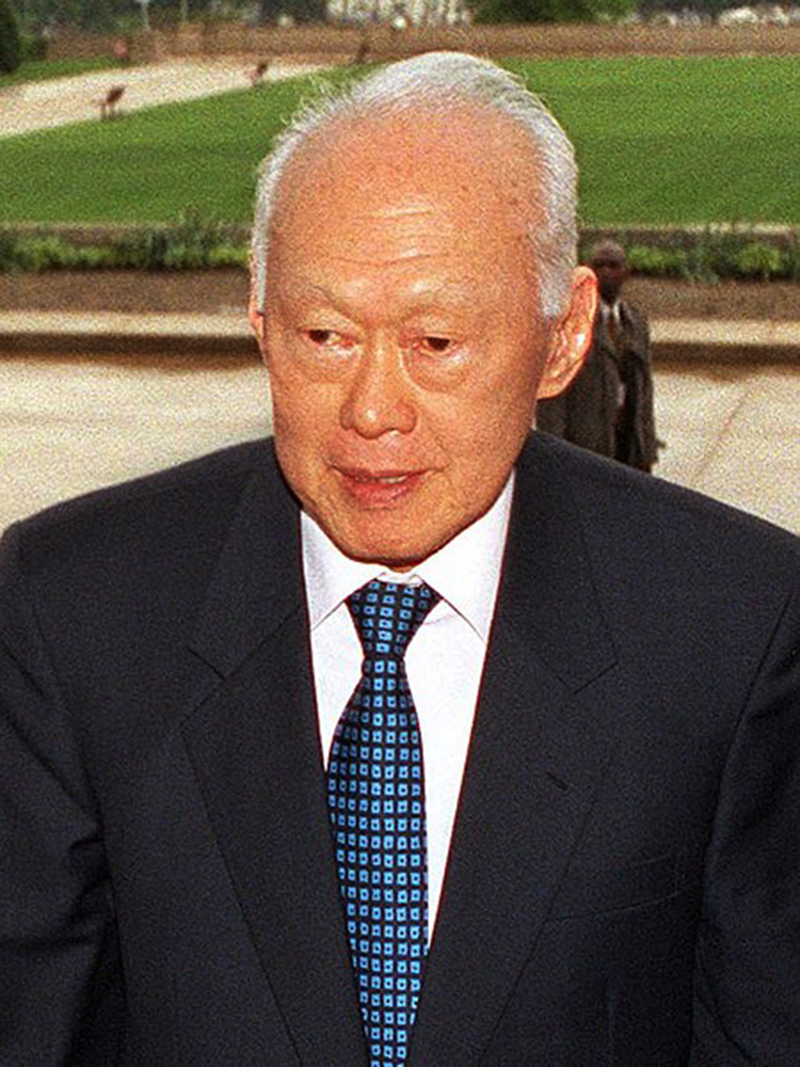

Lee Kuan Yew and Forbes Burnham became Premiers in their respective countries around the same time in the early-1960s. They were both gifted men, both national scholars, both graduates from prestigious universities, and both eloquent lawyer-statesmen. Lee had to build a nation with three ethnicities. Forbes Burnham needed to build his nation from four, African, Amerindian, Indian, Mixed, with pockets of Chinese and Portuguese.

Today, Singapore is a stable nation and an economic powerhouse. Guyana, for its part, remains a fractured society that, until the recent arrival of energy resources, was among the poorest countries in the Western hemisphere. Are there insights that might be gained from Lee Kuan Yew’s strategies of nation-building that Guyanese would do well to ponder? We think there are.

Henry Kissinger has just published six studies in world strategy in a book entitled Leadership. Lee Kuan Yew features prominently as a nation-building as well as an international strategist. The chapter on Lee is riveting, as is characteristic of Kissinger the strategist.

The first thing to note about Lee Kuan Yew is that he was a man of deep intellect who reasoned issues practically and developed policies through this process. He was no saint, and he himself admits that he did some harsh things like locking up some opponents. But he saw it as his challenge to build up a Singaporean nation and to give it the means of survival and prosperity – even if it lacked resources except for its strategic location and its port. And he succeeded brilliantly in these objectives. How did he do it?

Lee would write, at one stage: “There are books to teach you how to build a house etc. But I have not seen a book on how to build a nation out of a disparate collection of immigrants from China, British India, the Dutch East Indies, or how to make a living for its people when its former economic role as the entrepot of the region is becoming defunct.” Lee would build his nation block by block – and its stability and prosperity.

Early on, in 1965, Lee declared: “We are going to have a multi-racial nation in Singapore. We will set this example. This is not a Malay nation; this is not a Chinese nation; this is not an Indian nation. Everybody will have his place…Let us unite, regardless of race, language, religion, culture.” Early on, Lee brought in a system of racial and income quotas in Singapore’s housing districts which first put a limit on ethnic segregation and then progressively eliminated it. By living and working together, Singaporeans from disparate ethnicities and religions began to develop a national consciousness.

Kissinger notes that, unlike many other post-colonial leaders, Lee did not seek to strengthen his position by pitting the country’s diverse communities against each other. To the contrary, he relied on Singapore’s ability to foster a sense of national unity out of its conflicting ethnic groups. As Lee put it in 1967: “It is only when you offer a man – without distinctions based on ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and other differences – a chance of belonging to this great human community, that you offer him a peaceful way forward to progress and to a higher level of human life.” Lee’s approach was neither to repress Singapore’s diversity nor to discount it, but to channel and manage it. Any other course, he thought, would make governance impossible.

Lee’s signature strategy was to build on education for his people. Between 1960 and 1963, Singapore’s educational expenditure rose nearly seventeen-fold, while the school population increased by fifty percent. In his first nine years in power, Lee set aside nearly one-third of Singapore’s budget for education. He was determined to build up a meritocracy as the basis for Singapore’s growth and development.

Lee strenuously combatted corruption. Within a year of taking office, his government passed the Prevention of Corruption Act, which imposed severe penalties for corruption at every level of government. Under Lee’s leadership, corruption was swiftly and ruthlessly suppressed.

Corruption in Singapore is understood not only as a moral failing of the individuals involved but also as a transgression against the ethical code of the community, which emphasizes meritocratic excellence, fair play and honourable conduct. Lee declared at one stage: “You want men with good character, good mind, strong convictions. Without that, Singapore won’t make it.” Singapore has regularly been ranked as one of the least corrupt countries in the world.

To achieve his objectives, Lee relied on penalizing civil servants for failure rather than encouraging them by raising their salaries. Only in 1984, when Singapore had become wealthier, did Lee adopt his policy of pegging civil servants’ salaries at 80 percent of comparable private-sector rates. As a result, government officials in Singapore became some of the best compensated in the world.

Lee’s emphasis on the quality of life turned into a defining aspect of Singapore’s ethos. Beginning with a 1960 campaign against tuberculosis, Singapore made public health a major priority. Protection of the environment was another of Lee’s early priorities.

Lee was passionately concerned about public order and about public participation in governance. To orchestrate a revolution in governance, he established a network of ‘parapolitical institutions’ to serve as a transmission belt between the state and its citizens. Community centres, citizen’s consultative communities, residents’ committees and town councils provided recreation, settled small grievances, offered such services as kindergartens and disseminated information about government policies. Lee considered that one source of Singapore’s continuing strength was its first-past-the-post electoral system.

Lee once summarised his life’s work as such: We didn’t have the ingredients of a nation, the elementary factors: a homogenous population, common language, common culture and common destiny. To will the Singaporean nation into being, he acted as if it already existed and reinforced it with public policy. And he succeeded magisterially.

Guyanese can learn many lessons from the nation-building strategies of Lee Kuan Yew. One of them is the role of intellect and public policy in governance.