Today’s column re-visits my original advisement on local content requirements. Five years ago, I had offered the view that three broad policy priorities were seemingly leading Government’s preparations for impending oil and gas-based extraction. These priorities were: 1) establishing a sovereign wealth fund (SWF) and, relatedly, designing a fiscal regime for the sector; 2) providing a best practices governance framework, alongside a stand-alone regulatory commission for the extractive sector; and seeking membership of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI); and, 3) creating a local content requirements (LCRs) regime, the latter being today’s topic

What is “local content?”

Readers might recall my earlier observation that the notion of “local content” has been rapidly evolving since the 2000s. At the beginning it simply meant “that a producer ensures a certain percentage of inputs in the production process comes from local sources.” (S. Lester, International Economic Law and Policy Blog, 2013) Nowadays, the notion embodies emphasis on the localization of production, growth, and development potential. This outcome has occasioned strong debates around whether “state policies promoting localization create barriers to trade”? And, if they do, are these legally consistent with free trade provisions of the World Trade Organization (WTO)?

Thus, Silva (2013) has bluntly asserted: “The aim of LCRs is to create rent-based investment and import substitution incentives.” He elaborates and claims LCRs direct foreign investors/companies to ensure a minimum threshold of goods and services is procured locally. This directive is, effectively, the creation of import quotas by Government fiat! Such development is simply a policy shift from protected export platforms in developing countries (which thrived in the 1960s and 1970s) to welcoming foreign direct investment (FDI) and then imposing LCRs. Such a policy shift, reduces the investment risk in poor countries.

LCRs origins

The development rationale for LCRs in Guyana is rooted in the country’s historical dependence on the fortunes and misfortunes of extractive industries sales in world markets. While the goals/aims of LCRs are many, I have concentrated these to seven: 1) to secure growth and development offsets for when oil and gas revenues peak because depletion rates have also peaked; 2) to leverage oil and gas revenues for downstream value-added products; 3) consequent to 2, to promote economic diversification through non-extractive sectors growth; 4) to strengthen inter-industry linkages (backward and forward); 5) to place R & D and innovation centrally in Guyana’s productivity, growth and development; 6) to combat environmental challenges (degradation, destruction, pollution) to our biodiversity, and 7) to foster economic, political and social stability.

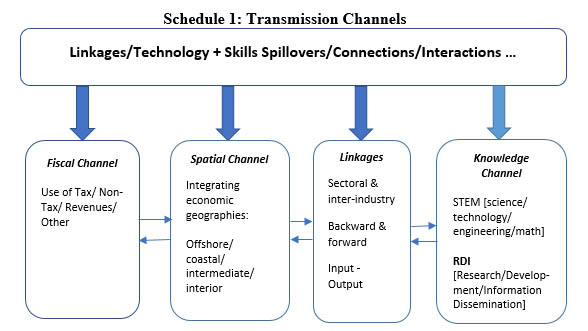

Forms of Linkages

Researchers who have studied these phenomena have identified four major forms of linkages, based on global practices aimed at breaking down enclave features through LRCs. These are: first the use of fiscal transfers. This entails mobilizing revenues through taxes and non-tax sources (sale of assets – land) from the oil and gas value chain. It also includes capital spending by the state on beneficial activities, which the oil and gas sector qualifies for (a good example being spending on infrastructure).

Second, there are spatial linkages. In Guyana, these include government spending on items like infrastructure, transport, communications, and ports. These enhance the geographic (spatial) integration of Guyana’s off-shore, coastal, intermediate, and interior geographies and their economic cohesion.

Third, there are linkages through knowledge development; for example, training in STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) and public spending dedicated to Research & Development, as well as Innovation (RDI).

Finally, inter-sectoral and inter-industry linkages are also advanced. There are both forward linkages (downstream value-added activities, like processing, services) and backward linkages (supplies of inputs to the sector, like consumables, services (accommodation, business-related), as well as other goods and services.

If this occurs, the enclave sector could be integrated, through those channels, with the non-enclave sectors, rather than crowd them out.

LCRs and Protectionism

Consequent to the above, as anticipated the notion of LCRs having evolved from the view that it was referring simply to the percentage share of local inputs that must be embodied in a domestic producer’s output to now where it is deemed to encompass constructs of localization and indigenous control/ownership, has generated debates as to whether CRs conflict with WTO principles. However, I noted also that, empirically, most countries, large and small, rich and poor, industrialized and non-industrialized and located on every continent and region of the globe have implemented and continue to implement LCRs. This contrast between WTO trade principles and global practices creates hidden pitfalls, which local Authorities, and the broader public should be aware.

I had suggested then that the best defense of the view, which most Guyanese intuitively hold – that is, LCRs for Guyana are fair and just – is indeed rooted in economic theory. I tried, therefore to indicate in those columns “the development rationale for LCRs in Guyana is rooted in the country’s historical experiences of extensive and intensive dependence on the vicissitudes of extractive industries operating in global markets and the peculiar characteristics of the petroleum sector.”

Indeed, I elaborated on this with specific discussions on: 1) the enclave economy; 2) the infant industry notion; 3) economic linkages and spillovers; and, 4) Caricom as a production platform for Guyana. I was careful to insist that the reputed case for LCRs as a form of “backward backdoor protectionism” should not be dismissed lightly. If the Authorities do this, they risk great legal peril.

Conclusion

Next week I conclude discussion of this topic.