“What’s life if we don’t repeat our stories?”

– Boubacar from “Liquid Twilight” by Ytasha Wowack

I am always mindful about what I want to review for Emancipation Day. It’s important to continually re-examine the history of slavery and colonisation, and to identify and challenge the ways its insidious legacy lingers in our present, shaping our systems, societies, and cultures.

But stories of darkness are not the only ones out there. There is a trail of lights leading from the past to the present, lights sparked by the resistance and resilience that have brought African people and the African diaspora to this point in history. These lights are a collective of our art, literature, political activism, grass-roots movements: everything that we have done — however great or small — to make our today better than yesterday. The lights do not just stop here. Our actions in the present ignite more of them which overtake us to spread like wildfires into an uncertain future.

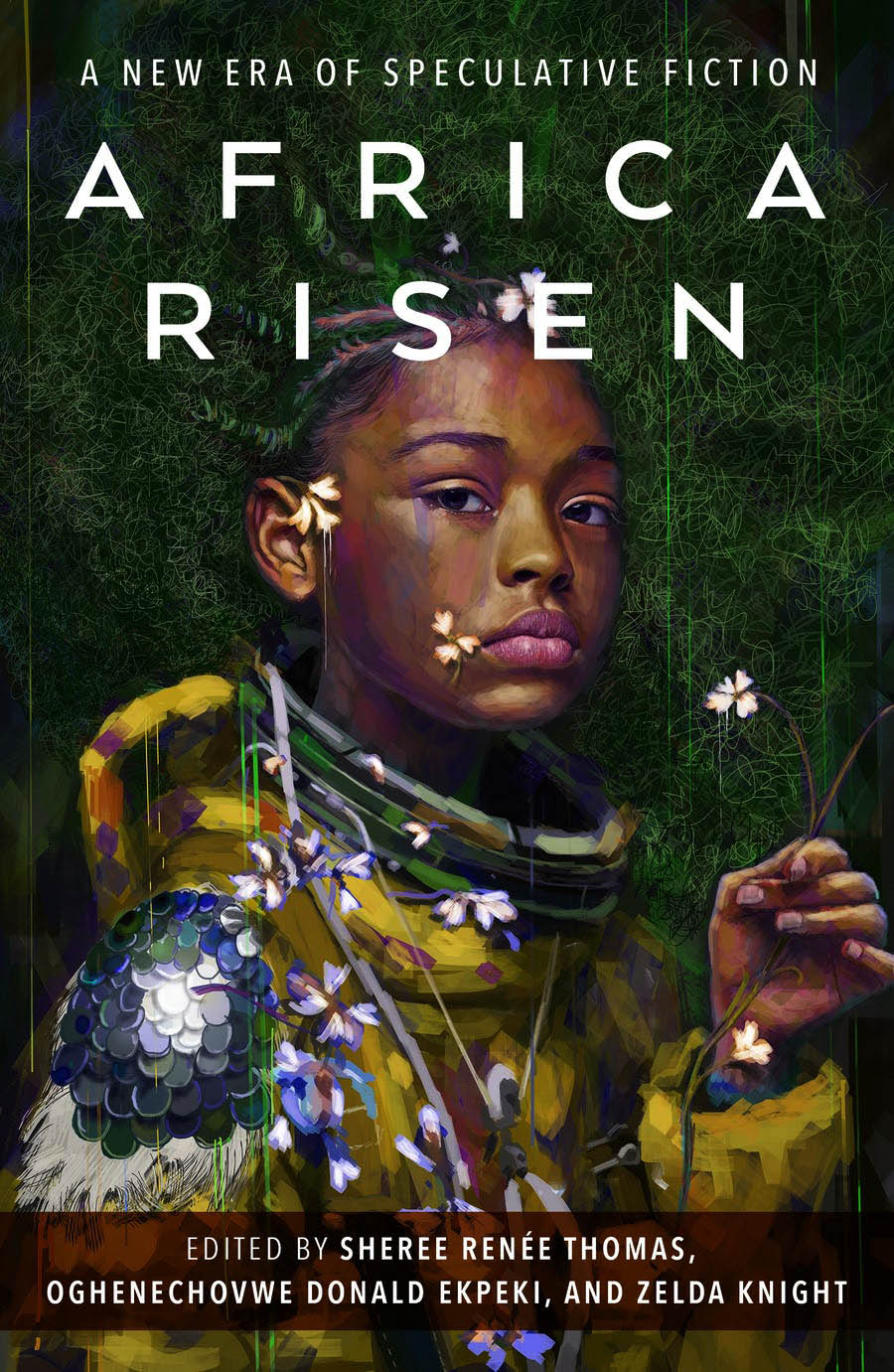

Africa Risen: A New Era of Speculative Fiction, edited by Sheree Renée Thomas, Oghenechovewe Donald Ekpeki and Zelda Knight, is a collection that sees, acknowledges, embraces, and explores this trail of lights. The introduction of this collection promises that the anthology celebrates the growing population of African and Afro-diasporic speculative fiction authors by offering a sample of their stories and their contributions to the genre.

It also firmly asserts that Africa Risen is not a collection that stands alone. As the editors mention in the opening lines of the introduction: “As the origin of humanity and home to the world’s oldest civilisations, Africa is the origin story of storytelling.” Therefore, by that logic, Africa and its storytellers have always been around, making work and making change. This collection is only one light along the trail that extends toward our future. It is a part of an ongoing movement, rather than a single moment.

Collectively, the 32 stories in this anthology follows the path I identified. The authors —both continental and diasporic, and at different stages of their writing careers — explore the past and present, and make speculations about our future through horror, science fiction, fantasy, surrealist fiction and fabulist tales. This careful curation by the editors displays the diversity, wealth and power of African literary tradition.

While I wish that I could cover all 32 stories in this anthology, I have neither the time nor the space. But I can talk about the ones that affected me at different points along the trail of lights.

Reconnecting with our Past

There are several stories in this collection that examine the past. But what delighted me the most was that they offered opportunities for me to learn about histories and legends I’ve never heard about before.

“Housewarming for a Lion Goddess” by Aline-Mwezi Niyonsenga is one of those stories. In it, Niyonsenga tells the tale of the lion goddess Nyavirezi, as she settles into a new house in the modern era and prepares a housewarming feast. While she cooks and prepares and tries to push her new young lover away, snippets of her past as the wife of a great warrior in the service of the Kingdom of Rwanda filter back to her. Slowly, she learns to accept her shortcomings, forgive herself, and make the best of her present.

“The Soul Would Have No Rainbow” by Yvette Lisa Ndlovu begins with Langa attending her grandmother Gogo’s funeral. Her relatives have already divided up her grandmother’s belongings for themselves and only left two things behind: her grandmother’s battered cookbook and the locked door to her basement. Within the cookbook she finds a note, a key, and an unfamiliar word, “Nomkhubulwane”, and the drawing of a praying mantis. Little by little, as Langa pages through her Gogo’s cookbook, she begins to put together a timeline of her grandmother’s past, find clues about her true identity, and her unique and instrumental role as a freedom fighter in the Zimbabwe War of Liberation.

“A Girl Crawls in a Dark Corner” by Alexis Brooks De Vita is one of only three stories in the collection that explicitly deals with slavery. In it, a nameless woman is given a gnarly task by her owner: to perform a female genital mutilation surgery on a young girl. Ever since purchasing her, her master has been fascinated by the scar between her legs, and as the story begins, he’s eager to see her replicate the surgery on others. Her first subject does not survive the procedure and thereafter haunts the shadows of her hut, demanding blood. But the man keeps bringing women to her, hoping to recreate the procedure at the expense of other young women and girls. Eventually, his morbid curiosity comes back to bite him.

Confronting the Present

There are several stories in the collection that feel set in the present day, even if they explore futuristic or abstract concepts.

One great example is Tobias S. Buckell’s “The Sugar Mill”, in which a white-passing (looks light enough to pass for white) real-estate agent is trying to sell an old Sugar Mill to a white couple trying to settle on the Caribbean island he calls home. While he does so, the ghosts who haunt the sugar mill’s grounds — all of whom died from mill-related dismemberment accidents — haunt him, begging him not to sell another monument of his island’s history to white expats who want to turn it into a luxury house. But he’s in a conundrum: he’s already homeless because his own house was destroyed by a hurricane some years ago. Selling the sugar mill would give him enough money to turn his life around, but also force him to betray his ancestors for cash. Buckell’s story explores the intersection of post-hurricane gentrification in the islands and the predatory capitalism that drives it, as well as the current disturbing trend of white people turning slave cabins, plantation houses and, in this story’s case, sugar mills into Airbnbs and luxury rentals.

“Air to Shape Lungs” by Shingai Njeri Kagunda is a surrealist piece written from the perspective of a group of migrants or refugees as they float anxiously somewhere in the atmosphere. It’s the year of deportation, they say, and this sudden and brutal untethering from safe ground gives them the ability to fly. As they wander the world, gravity begins to pull them down. Some find new places to settle down, while others remain in suspended, in limbo, unable to find a place for themselves on the ground. Throughout this short, poetic story, Kagunda explores the reality faced by migrants, who are forced to be nomadic, and directly challenges the double-standards of travel for global north vs global south citizens.

Lastly, there is Ada Nnadi’s comedic story “Hanfo Driver” which centres this terrifying premise: what if minibuses could fly? This is the predicament that Fidelis must confront when his Oga Dayo calls him in for work in the morning. His “uncle”/caretaker/employer is known throughout their part of town as an adventurous entrepreneur who sinks his money into well-meaning but disastrous ventures. His latest idea, the hoverdanfo, aims to revolutionise Nigeria’s public transportation system and he wants Fidelis to drive it. The thought alone is enough to make Fidelis’ stomach churn. But he needs the money, so he reluctantly participates in Oga Dayo’s sketchy plan and drives the patchwork floating danfo around town for him, not knowing that this is all a part of Oga Dayo’s wholesome, albeit risky, plans for Fidelis.

Dreaming of Stranger Futures

Stories that talk about the future take up the most space in this anthology. I loved reading these writers’ imaginations for the world going forward, both the wholesome ones and the terrifying ones.

“The Blue House” by Dilman Dila, “Mami Waterworks” by Russel Nichols and “Cloud Mine” by Timi Oduseso are all set in the aftermath of a climate-change apocalypse.

“The Blue House” is the outlier among these three. Its protagonist is a bicycling android who has been salvaging materials and parts to keep her body and bicycle in their best condition she peddles across the desolate wasteland. It seems like she has survived for years this way, but it all comes crashing down when she sees The Blue House on a distant plateau. The sight of The Blue House triggers a memory systems reboot, which then sparks an internal conflict between it and her organic security systems. Her memory system is determined to investigate The Blue House, and her security system tries to override this impulse because of the risks it poses to the organic system. Memory wins each time, and she struggles to make her way to The Blue House, overclocking her last CPU and overheating several times along the way, all while beginning to piece together snippets of who she was before the devastating climate crisis ended her world.

“Cloud Mine” and “Mami Waterworks” are so similar that they almost feel like they are in conversation with each other, possibly even in the same universe, talking about similar communities in similar problems. Both stories are set in countries devastated by drought and explore the ways the communities are trying to survive.

In “Cloud Mine”, Salim’s people once mined for water to overcome the drought, first digging into the earth and then trying to capture and siphon clouds using their cloud mines. But ground water ran out and the sky is cloudless. Their only hope now rests on the back of Salim’s uncle, who went out weeks ago to procure a rainmaker from a neighbouring community. As they wait and ration water, Salim dreams of the day he, his best friend Hyelni and the rainmaker can play together in newly created pools and reservoirs. When his uncle returns with the rainmaker in tow, Salim and his people are saved, but the boy is devastated as his fantasies about the rainmaker are shattered.

“Mami Waterworks” proffers a different drought solution: people-centred technology. Amaya is a tinkerer who believes that remnants of old technology is the solution to her community’s struggles with perpetual drought. There’s only one problem: technology is the reason the world has crumbled and led to the drought in the first place, and she runs the risk for being burned at the stake for her heretical solutions. But Amaya is determined to make a change with her newest invention, the Mami Waterworks, which she believes will supplement her people’s limited supply of water and offer them emotional release while they wait for the next rains to come.

“Ruler of the Rear Guard” by Maurice Broaddus and “Ghost Ship” by Tananarive Due are two additional stories that also seem to be in conversation with each other. Both are about a fascist collapse of the United States and its effect on the people of colour forced to flee the country for their own safety.

In Broaddus’s story, Sylvonne Butcher has taken refuge in Ghana, where she’s being accommodated by representatives of the Pan-African Coordination Committee. She hopes to integrate into Ghanian society and become a member of the broader Pan-African movement. However, she quickly learns that she has a lot of unlearning and reconditioning to do if she wishes to assimilate into the continent and break the trauma bonds that still tie her to America.

Tananarive Due’s “Ghost Ship” goes in the opposite direction. Florida’s mothers were from America once, having fled from the country as it grew increasingly antagonistic toward people of colour. Instead of being welcomed with open arms into a continental bosom, however, they end up in South Africa, where they are forced into indentured labour and debt bondage. After their passing, Florida inherited their debt and was raised by the woman they owed in the past. Now, that woman is sending her back to America with a box of something that she wants delivered to the United States. Florida is excited for the trip to her homeland, for the opportunity to be away from the South Africa that hurt her and her parents so much, even if she feels unwelcomed just on the ship. The smuggling operation goes well at first…until the thing in the box gets away and slowly causes havoc of the ship.

Finally, the last story I want to touch on is “A Dream of Electric Mothers” by Wole Talabi. This is one of my favourite stories in the anthology. Brigadier-General Dolapo Balogun is the Défense Minister of the Odua Republic. After she and her fellow ministers fail to come to an agreement over their border dispute with the Kingdom of Dahomey, they agree to seek the dream counsel of their Electric Mother: a superconsciousness created as an ancestral collective which can serve as a government consultant when needed. But the border dispute is not her only reason for wanting to consult the Electric Mother. She believes it holds the answers to her mother’s death as well as a connection to her ancestor who created the Electric Mother. Thankfully, the digital entity is happy to tell her and her ministerial cohort exactly what she needs to hear.

Conclusion

I wish that I had more space and time to write about this collection. Each of its 32 stories in it touched me differently. Some amused me and others creeped me out, but most delighted and educated me. Africa Risen is a raging fire, it’s crackling, a joyful chorus to excellence in African and Afro-diasporic writing. It introduced me to new writers just starting in their careers, and to established writers whose work I am now even more eager to explore.

Most importantly, it drew my attention to countries and cultures I was completely unaware of. “Housewarming for a Lion Goddess” was an introduction to Central Africa’s pre-colonial history and cosmology. “The Soul Would Have No Rainbow” taught me about Zimbabwe’s colonial history and anti-colonial struggles. “Hanfo Driver” taught me that Guyanese and Nigerian minibus culture are not so different. And the list goes on. The book as a whole is both entertaining and educational, piquing my curiosity enough to want to read more non-fiction about the places, times, and ideas represented within its pages.

I’m excited to see how this book will be received after its official release, and I look forward to seeing what projects the editors and included authors will be tackling in the future. I thoroughly enjoyed this reading.

Thanks to Tor.com for sending me an Advanced Reader Copy (ARC) of Africa Risen in exchange for an honest review. Africa Risen will be wildly available from November 15, 2022. Also special thanks to Alex Brown and Chloe of Thistle & Verse for helping me figure out how to get my first arc, and Desirae Friesen of Tor.com for helping me through the process of getting this arc. This review would not exist without you.

Want to read more African Speculative Fiction? Here is a list of some of the anthologies and collections mentioned with in the introduction of Africa Risen:

Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora edited by Sheree Renée Thomas

Whispers from the Cotton Tree Root edited by Nalo Hopkinson

Dark Faith edited by Maurice Broaddus and Jerry Gordon

Dark Thirst edited by Omar Tyree, Donna Hill and Monica Jackson

Voices from the other side edited by Brandon Massey

Griots: A Sword and Soul Anthology edited by Milton J. Davis and Charles R. Saunders

Slay: Stories of Vampire Noire edited by Nicole Givens Kurtz

A Phoenix First Must Burn edited by Patrice Caldwell

Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora edited by Zelda Knight and Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki

New Suns edited by Nisi Shawl