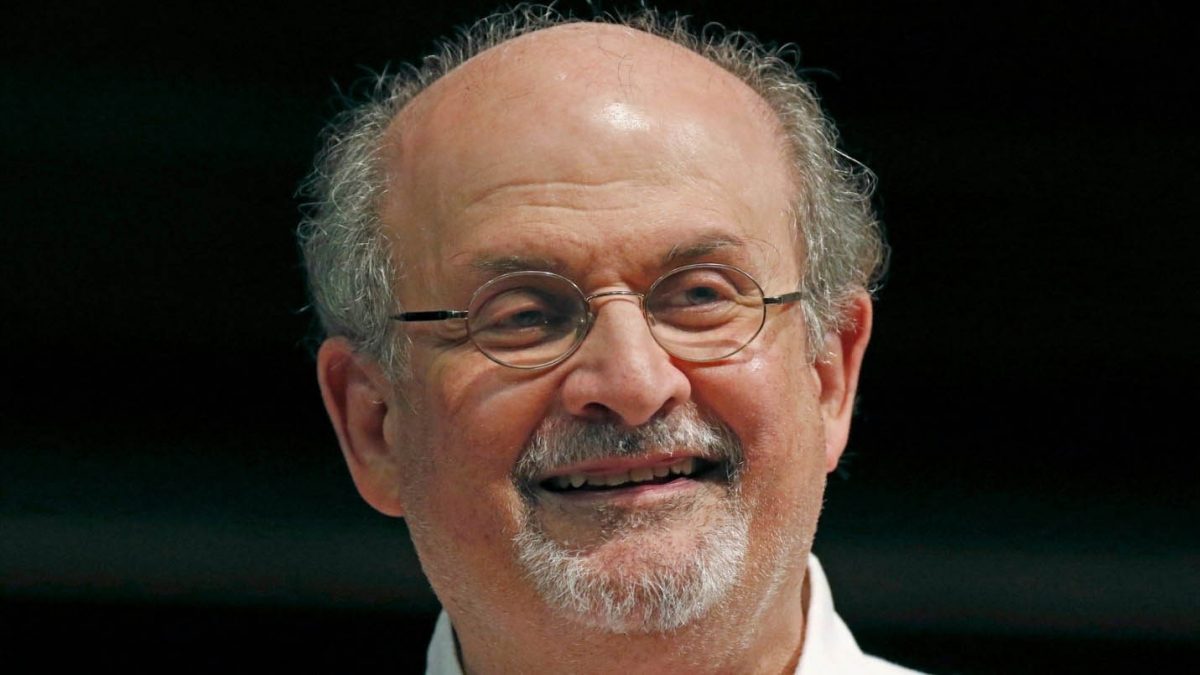

NEW YORK, (Reuters) – Salman Rushdie, the Indian-born novelist who spent years in hiding after Iran urged Muslims to kill him because of his writing, was stabbed in the neck and torso onstage at a lecture in New York state yesterday and airlifted to a hospital, police said.

After hours of surgery, Rushdie was on a ventilator and unable to speak last evening after an attack condemned by writers and politicians around the world as an assault on the freedom of expression.

“The news is not good,” Andrew Wylie, his book agent, wrote in an email. “Salman will likely lose one eye; the nerves in his arm were severed; and his liver was stabbed and damaged.”

Rushdie, 75, was being introduced to give a talk to an audience of hundreds on artistic freedom at western New York’s Chautauqua Institution when a man rushed to the stage and lunged at the novelist, who has lived with a bounty on his head since the late 1980s.

Stunned attendees helped wrest the man from Rushdie, who had fallen to the floor. A New York State Police trooper providing security at the event arrested the attacker. Police identified the suspect as Hadi Matar, a 24-year-old man from Fairview, New Jersey, who bought a pass to the event.

“A man jumped up on the stage from I don’t know where and started what looked like beating him on the chest, repeated fist strokes into his chest and neck,” said Bradley Fisher, who was in the audience. “People were screaming and crying out and gasping.”

A doctor in the audience helped tend to Rushdie while emergency services arrived, police said. Henry Reese, the event’s moderator, suffered a minor head injury. Police said they were working with federal investigators to determine a motive. They did not describe the weapon used.

White House National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan described the incident as “appalling.” “We’re thankful to good citizens and first responders for helping him so swiftly,” he wrote on Twitter.

Rushdie, who was born into a Muslim Kashmiri family in Bombay, now Mumbai, before moving to the United Kingdom, has long faced death threats for his fourth novel, “The Satanic Verses.”

Some Muslims said the book contained blasphemous passages. It was banned in many countries with large Muslim populations upon its 1988 publication.

A few months later, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, then Iran’s supreme leader, pronounced a fatwa, or religious edict, calling upon Muslims to kill the novelist and anyone involved in the book’s publication for blasphemy.

Rushdie, who called his novel “pretty mild,” went into hiding for nearly a decade. Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator of the novel, was murdered in 1991. The Iranian government said in 1998 it would no longer back the fatwa, and Rushdie has lived relatively openly in recent years.

Iranian organizations, some affiliated with the government, have raised a bounty worth millions of dollars for Rushdie’s murder. And Khomeini’s successor as supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, said as recently as 2019 that the fatwa was “irrevocable.”

Iran’s semi-official Fars News Agency and other news outlets donated money in 2016 to increase the bounty by $600,000. Fars called Rushdie an apostate who “insulted the prophet” in its report on Friday’s attack.

Rushdie published a memoir in 2012 about his cloistered, secretive life under the fatwa called “Joseph Anton,” the pseudonym he used while in British police protection. His second novel, “Midnight’s Children,” won the Booker Prize. His new novel “Victory City” is due to be published in February.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson said he was appalled that Rushdie was “stabbed while exercising a right we should never cease to defend.”

Rushdie was at the institution in western New York for a discussion about the United States giving asylum to artists in exile and “as a home for freedom of creative expression,” according to the institution’s website.

There were no obvious security checks at the Chautauqua Institution, a landmark founded in the 19th century in the small lakeside town of the same name; staff simply checked people’s passes for admission, attendees said.

“I felt like we needed to have more protection there because Salman Rushdie is not a usual writer,” said Anour Rahmani, an Algerian writer and human rights activist who was in the audience. “He’s a writer with a fatwa against him.”

Michael Hill, the institution’s president, said at a news conference they had a practice of working with state and local police to provide event security. He vowed the summer’s program would soon continue.

“Our whole purpose is to help people bridge what has been too divisive of a world,” Hill said. “The worst thing Chautauqua could do is back away from its mission in light of this tragedy, and I don’t think Mr. Rushdie would want that either.”

Rushdie became a U.S. citizen in 2016 and lives in New York City.

A self-described lapsed Muslim and “hard-line atheist,” he has been a fierce critic of religion across the spectrum and outspoken about oppression in his native India, including under the Hindu-nationalist government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

PEN America, an advocacy group for freedom of expression of which Rushdie is a former president, said it was “reeling from shock and horror” at what it called an unprecedented attack on a writer in the United States.

“Salman Rushdie has been targeted for his words for decades but has never flinched nor faltered,” Suzanne Nossel, PEN’s chief executive, said in the statement. Earlier in the morning, Rushdie had emailed her to help with relocating Ukrainian writers seeking refuge, she said.