In today’s column I wrap- up last week’s presentation dealing with the economic rationale behind the creation of a state-owned NRF or SWF to be used for effective regulation of the anticipated medium-term boom in oil revenues and the efficient spending of same revenues. Afterwards I offer brief comments on the repeal of the NRF Act 2019 and its replacement with NRF Act 2021. Next week I conclude my revisit of this topic and offer my updated recommendation on it.

Wrap-up

Five and one-half years ago, back in very early 2017, in my initial discussion of SWFs, I had advocated that, global experiences suggest Guyana should only consider a SWF designed with two basic considerations at the forefront: namely, 1) avoiding/controlling inevitable threats and risks accompanying rapid expansion of oil exports pose; and, 2) seek to propel the economy along a path that efficiently seizes development opportunities as they emerge.

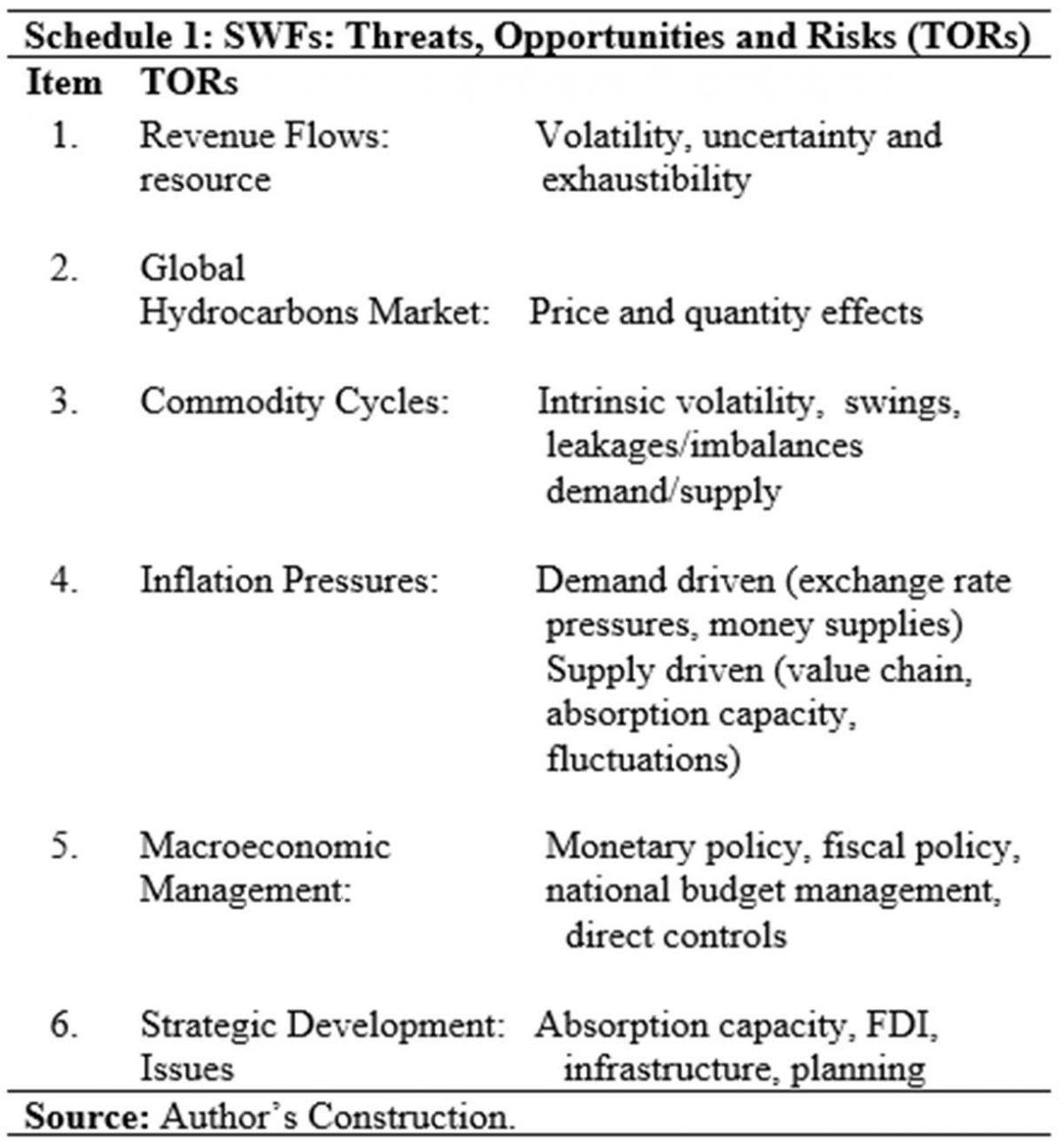

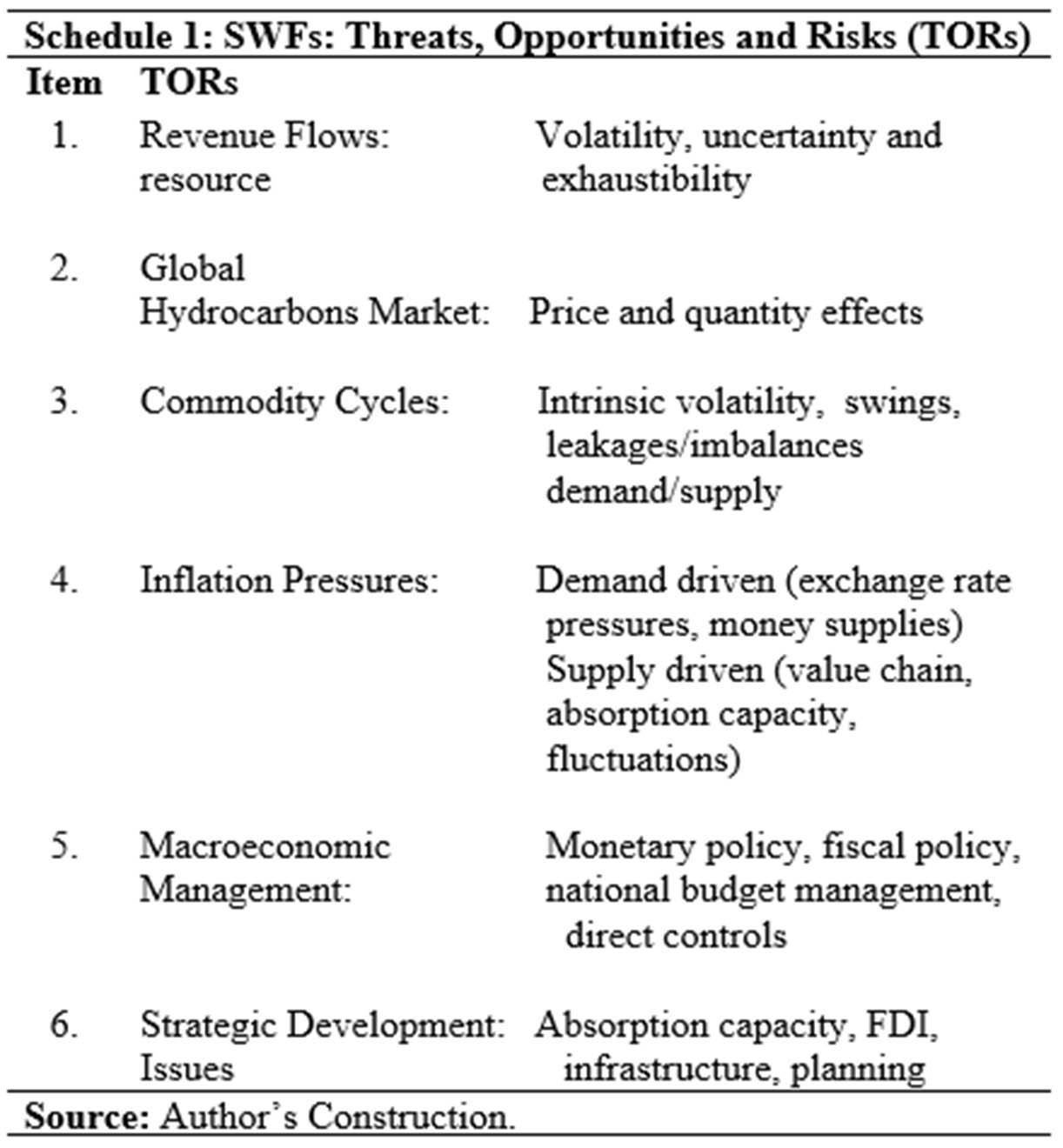

In such circumstances, five risks/threats typically appear, along with two opportunities, which must be seized. A key risk is the disruption effects of volatile, uncertain and consequently unpredictable revenue flows. Typically, these disruptions are readily compounded by the opportunity time-horizon the country faces, given its petroleum resource depletion/exhaustion rate. Such risks are universally observed in the global hydrocarbons market, where price and quantity effects are manifest; and discernible, in the form of repeated oil and natural gas “commodity cycles”.

Experiences show that such occurrences create inflationary pressures on both the demand (expenditure) and supply (cost) sides of the market. Prudent macroeconomic management offers scope for containing these threats/risks, particularly through the mechanisms of sensible national budget management. These mechanisms however, require strategic focus on situating development priorities correctly. Here experience again suggests that focus on 1) the absorption capacity of the non-oil sectors, 2) the facilitation of synergetic foreign direct investment (through institutional and policy changes), 3) the build-up of infrastructure, and 4) careful development planning and policy formulation are all central to the country’s ability to convert threats/risks into opportunities. I had constructed Schedule 1 below to show this for the benefit of readers.

As readers are aware, a state-owned special purpose investment vehicle was established in 2019 under the NRF Act, 2019 by the then David Granger Administration designed to 1) receive revenues from all Guyana’s natural resources sales, 2) invest these in financial instruments and 3) to disperse these as permitted/authorized to the Annual National Budgets of the Government of Guyana, GoG. With the highly contentious change in political Administration in August 2020, the 2019 Act was doomed to be repealed. Indeed, it was and the present NRF Act 2021 replaced it in December of that year.

I use the term “doomed to be repealed” advisedly. This is because the 2019 Act was caught in the cross-hairs of a tumultuous political target; that is the 2019 Act was passed by a political administration in office, after having been defeated in a no-confidence motion brought against it in the previous year. Other concerns were publicly raised but the political passions prevailing then would not have allowed an “all party consensus” on NRF legislation for Guyana, an essential for its success!

It is worth noting that, other critiques with merit were widely circulated. Thus 1) the NRF Act was turgid, dense, and opaque, which defeated the aim of broad-based enthusiastic public buy-in; 2) more specifically, the formula governing the sources, uses, limits, and ceilings was unnecessarily complicated and 3) political control of resources too burdensome.

Replacement NRF Act 2021

Changes to the 2019 Act were clearly more than simply Amendments; reflecting the deep controversy behind the political opposition to it. To take a couple of significant examples. First, the 2021 Act focused on hydrocarbons revenues exclusively, while the 2019 Act was based on revenues from all mineral extractives. Second the 2021 Act created a Board of Directors to share responsibility for the administration of sources and uses of the requisite hydrocarbon revenues. This was represented as diluting excessive concentration of authority in the hands of the Minister of Finance.

In response to an editorial by Stabroek News the Ministry of Finance put out an official Statement on the new 2021 Act on December 17, 2021. It pronounced bluntly that, the new Act “dismantles APNU/AFFC’s architecture for Ministerial involvement and interference” in the NRF, which goes to the gravamen of their differences; allegation of a “one man show” or Ministerial domination.

With these comments I turn to a critique of the extant NRF Act 2021 and revisit of my recommendation of a NRF for Guyana at this stage of the emergence of its infant oil and gas sector.

Critique and Recommendation

A serious critique of Guyana’s NRF operates at two levels of abstraction. One is the interrogation of its processes as fixed in law, regulation and practice [Level 1]. The second is focused on its properties as a social construct, abstraction and theoretical idea/notion. I’ll proceed on the sequence indicated here. My recommendation will follow the critique

Conclusion

Next week’s column addresses the two topics. .