On Sunday, Aramco, the national energy company of Saudi Arabia, reported a profit of US$48B for the second quarter of 2022. It is a staggering amount from the largest corporation by market cap in the world.

Like many oil companies, 2022 has been good for Aramco following the catastrophic circumstances caused by Covid-19. This two-year period reflects both the historic volatility of crude markets (going from a low of US$21 per barrel of Brent Crude in April 2020 to a high of US$120 in April 2022) and how integral the commodity still is to the world economy. The recent high prices have also made many Middle Eastern countries who are low cost and high volume producers, immensely wealthy. If the status quo continues it will likely mean changing power dynamics in the geopolitical sphere. Bulging with cash they have made investments worldwide, some wise some not so. Most high-profile but mere baubles for them has been in the area of sports including the takeover of Manchester City by the Abu Dhabi United Group in 2008; Qatar Sports Investments buying Paris Saint-Germain in 2011; the purchase of UK premier league side Newcastle United by a Saudi fund in 2020; and most recently the creation of the LIV Golf Tour with extravagant signing fees for players who defect from rival tours.

Middle Eastern money and its insatiable spending on military hardware, has always complicated Western foreign policy with its veneer of promoting democracy and human rights. We have had a taste of this in recent weeks with US President’s Joe Biden’s trip to Saudi Arabia and other countries. He met with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman despite, during his bid for the presidency in 2019, vowing to make Saudi Arabia “the pariah that they are” for the gruesome killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

The two limited themselves to a public fist bump while Biden was deliberately reticent in his body language towards the Prince. Incidentally, choosing to shake or not shake hands is never a trivial matter. The First British/China Opium War (1839 to 1842) was precipitated in part by the refusal of Lord Macartney to perform the elaborate prostration or “kowtow” before Emperor Qianlong.

This turnaround by Biden was stark but he is simply following a continuation of US foreign policy that is highly malleable depending on the country and circumstances. A similar shift can be seen vis a vis Venezuela. After years of sanctioning and undermining the Chavez/Maduro regimes it is now softening as America looks towards its energy security rather than what has been utterly futile attempts at regime change.

In the end Biden’s Saudi visit only underlined America’s waning influence, since its primary purpose was to persuade OPEC to increase oil production. In the event when OPEC Plus met a few days later the 100k barrel per day increase was the smallest ever announced – almost an insult. What seems increasingly clear is that the grouping along with Russia is probably more cohesive than at any time in its history. This is partly because many in the group are pumping at maximum volumes and not even meeting their quotas, after years of under-investment. That means they are not squabbling over who gets to pump more. The only factor keeping prices in check is China’s long emergence from Covid-19 and concerns about the resilience of its economy including in its real estate sector. Long term, OPEC must be thinking that with the world said to be transitioning to renewables they should maximise profits while they can. The present day effect has been high prices at the pump for Western motorists. Add to this a natural gas crunch in Europe, caused by the war in Ukraine and uncertainty over adequate supplies for the winter, and inflation is on the march, creating a cost of living crisis and destroying savings. Inflation in the UK hit 10.1% in July – a 40-year high. Price increases are in turn fueling industrial action by unions across Europe, and to some extent the USA where an accelerating house price decline is perhaps of more concern.

It all means the West is entering a period of high political and economic instability that has already seen the ouster of Mario Draghi as Italian Prime Minister and UK PM Boris Johnson. Such periods inevitably boost populist movements both on the left and right (see Germany pre-World War II) and in the current context the United States faces the previously unimaginable return of Donald Trump in 2024.

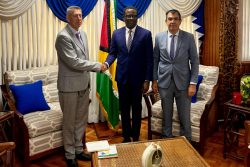

Even a little country like Guyana is feeling the influence of Middle Eastern wealth. Indeed it is actively encouraging investments although none has come to fruition yet despite numerous delegations back and forth since August 2020. Last month’s visit of a 50-member delegation from Saudi Arabia was the most significant and the most controversial. Just like handshakes, in diplomacy, what one wears matters. Many have defended the President’s decision to wear the traditional thawb, ghutrah and iqal, as being a gesture of religious kinship but the outfit is actually secular and unique to the region with its hot weather. As such It was not appropriate, and reflected the more serious obeisance towards the delegation with its demands for a desk at the Minis-try of Finance and custom-made concessions.

The question should be what exactly do these countries want? The investments being talked about for Guyana require what they would consider to be pocket money, so it does not appear this interest is being driven primarily by economics. Another view is that these countries might be viewing our President as an ally who could help them get a toe-hold on a continent that has for centuries been off limits to Islam.

With a brand of Islam being highly political, indeed radical, in nature, will the US administration look the other way as it has largely done to China’s infiltration of Latin America? For its part the US administration rolled out the red carpet for President Ali in his recent visit, contrary to some interpretations, and this should be seen as a signal that America now wants a level of control in who gets to invest here.

For our own sake do these countries’ values meet our own constitutional aspirations to be a secular, religiously tolerant and gender equal society? Presi-dent Ali claims this is all part of a smart diplomatic strategy but it looks from the outside more like an ad hoc muddle, especially when one recalls the embarrassing Taiwan U-Turn. The government is desperate for investment as part of its purported infrastructure transformation but this is a country with no credit rating and a level of political discretion that is anathema to serious investors.

The larger picture is that while Chinese power and influence will threaten American hegemony, if the massive flow of money to oil producing states continues through this decade, we may need to add another actor to the geopolitical three-ring circus.