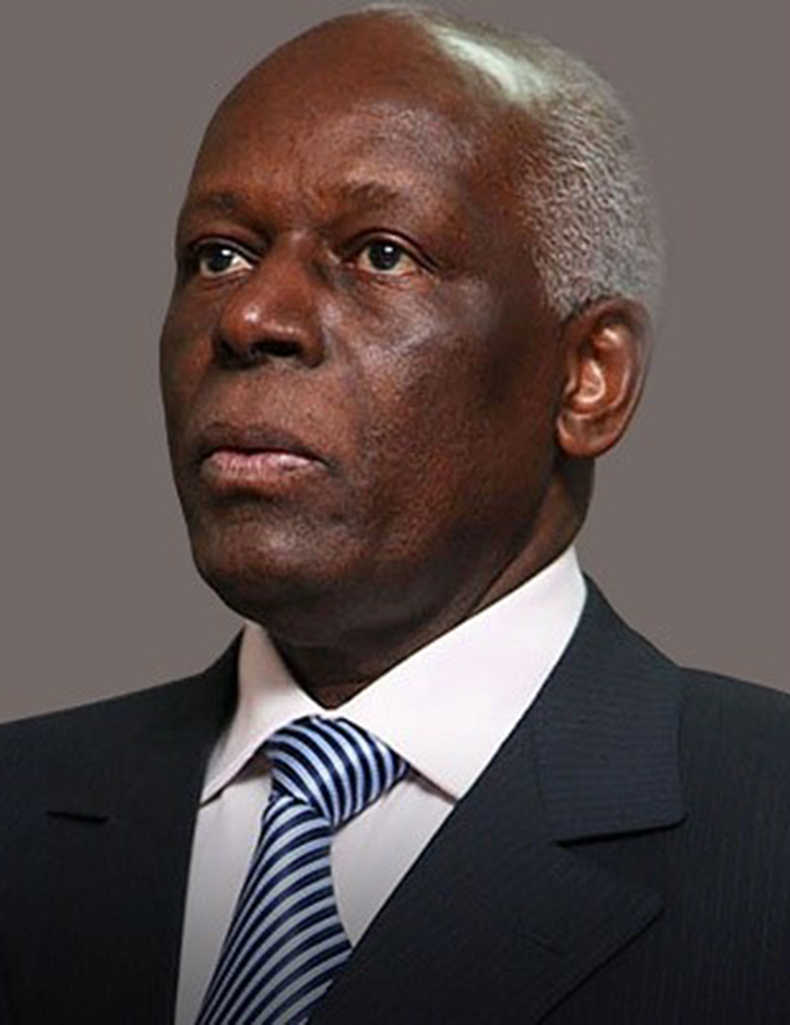

LUANDA, (Reuters) – The body of Angola’s former President José Eduardo dos Santos, who died in Spain in July, arrived in the Angolan capital Luanda last evening, casting a new element into a tense election campaign.

“The remains of José Eduardo dos Santos have arrived in Angola after a long waiting period,” Marcy Lopes, a government minister, told reporters shortly after the casket, draped in the Angolan flag, was taken off the airplane.

Critics of the ruling MPLA party worried that with a tight election due to take place on Wednesday, the party could seek to politicise the repatriation, diverting attention from the main opposition party UNITA’s campaign and from the electoral process.

The funeral is likely to take place on Aug. 28, Dos Santos’ birthday, MPLA spokesperson Rui Falcao said.

There have been weeks of uncertainty over the former president’s final resting place. Dos Santos, who stepped down in 2017 after 38 years in power, died on July 8 at the age of 79 at a clinic in Barcelona, where he was being treated following a long illness.

Lawyers representing dos Santos’s daughter, Tchize dos Santos, had successfully requested a full autopsy citing alleged “suspicious circumstances” of his death, without providing evidence, and had asked for him to be buried in Barcelona.

A Spanish judge ruled on Wednesday that the death was from natural causes, ruling out foul play, and allowed the release and repatriation of his body.

Outside the airport, a small crowd clapped as the funeral car transporting Dos Santos’ body drove off to Miramar, his former official residence in Luanda.

Angola is gearing up for an election that is likely to be the tightest since the first multi-party election there in 1992. The MPLA, which was dos Santos’ party and is that of President Joao Lourenço, has governed Angola since it won independence from Portugal in 1975.

UNITA is stronger than ever and anger is growing at government failures to convert vast oil wealth – Angola is Africa’s second-biggest oil producer – into better living conditions for all.

Launching his party’s campaign last month, Lourenço urged people to vote for the MPLA to honour Dos Santos’ legacy. Voters will elect a new parliament and president.

“It seems like a very transparent manoeuvre to monopolise the media, as usual,” Jon Schubert, a political anthropologist and Angola expert at the University of Basel, told Reuters, referring to the repatriation of Dos Santos’ body. Most Angolan media is controlled by the state.

Some critics of the government have also voiced concern the election may be tainted. The government did not reply to a request for comment about election transparency and fraud. The electoral commission, which is mostly controlled by the MPLA, said the election will be fair and transparent.

Some MPLA supporters said the return of the ex-president’s body to Angola was important to them.

Sónia, 41, an MPLA supporter at a big rally in the outskirts of Luanda on Saturday, said: “For us him coming back to Angola before the election shows the importance he had to create peace in our country.”

Justin Pearce, senior lecturer in history at South Africa’s Stellenbosch University, said that while Lourenço was battling to retain support he did not believe there was “any deep nostalgia for dos Santos in Angolan society”.

Although handpicked by dos Santos, Lourenço swiftly moved to investigate allegations of multi-billion dollar corruption during the former president’s era. Pearce said this was aimed at gaining “some popular legitimacy”.

Dos Santos never specifically responded to the allegations that he had allowed corruption to become rampant.

At Saturday’s rally, Lourenço told a cheering crowd the MPLA “broke” the corruption taboo and “really started the fight against” it.