WASHINGTON, (Reuters) – The U.S. economy contracted at a more moderate pace than initially thought in the second quarter as consumer spending blunted some of the drag from a sharp slowdown in inventory accumulation, dispelling fears that a recession was underway.

That was underscored by details of the report from the Commerce Department yesterday, showing the economy growing steadily last quarter when measured from the income side. The underlying economic strength fits in with recent upbeat readings on the labor market, retail sales and industrial production.

“We have had a tremendous recovery, this is a mid-cycle slowdown and not a recession,” said Brian Bethune, an economics professor at Boston College. “Employment is still growing, which means basically, production is still growing, but there are these supply chain problems.”

Gross domestic product shrank at a 0.6% annualized rate last quarter, the government said in its second estimate of GDP. That was an upward revision from the previously estimated 0.9% pace of decline. The economy contracted at a 1.6% rate in the first quarter. Economists polled by Reuters had expected GDP would be revised slightly up to show output falling at a 0.8% rate.

The two straight quarterly decreases in GDP meet the standard definition of a technical recession. But in the case of the U.S. economy, the contraction in GDP is misleading, given the large role played by inventories.

Supply chain disruptions have left unfinished products on factory floors or at shipping docks. These products cannot be included in GDP until they go into inventories.

Inventories rose at a $83.9 billion rate last quarter after increasing at a $188.5 billion pace in the first quarter. They subtracted 1.83 percentage points from GDP. Consumer spending grew at a 1.5% pace, revised up from the previously reported 1.0% rate. Shortages and the resulting higher prices have crimped spending.

An alternative measure of growth, gross domestic income, or GDI, increased at a 1.4% rate in the second quarter. GDI, which measures the economy’s performance from the income side, grew at a 1.8% pace in the first quarter. It is calculated using corporate profits, compensation and proprietors income data.

While GDI and GDP can diverge from one quarter to the other, there has been no convergence since the end of 2020, leaving a huge gap of 3.9 percentage points. Over the long run GDP tends to converge toward GDI, though that is not a golden rule.

“Hopefully at some point we will have fewer supply chain disruptions and production will catch up,” said Bethune. “Production will be higher than income, but we are a long way from that.”

The average of GDP and GDI, also referred to as gross domestic output and considered a better measure of economic activity, increased at a 0.4% rate in the April-June period, up from a 0.1% growth pace in the first quarter.

Stocks on Wall Street were trading higher. The dollar fell against a basket of currencies. U.S. Treasury prices rose.

RESILIENT LABOR MARKET

The income side of the growth ledger was boosted by strong profits as well as wage gains amid a tight labor market.

National after-tax profits without inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustments, conceptually most similar to S&P 500 profits, increased $284.9 billion, or at a 10.4% pace, accelerating from the 1.0% growth pace in the January-March period. They were boosted by gains in the energy sector as oil prices soared because of the Russia-Ukraine war.

Profits were 11.9% higher from a year ago.

The National Bureau of Economic Research, the official arbiter of recessions in the United States, defines a recession as “a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in production, employment, real income, and other indicators.”

The underlying economic strength is a double-edged sword. While it shows no recession, it gives the Federal Reserve ammunition to maintain its aggressive monetary policy tightening campaign, increasing the risk of a downturn.

The U.S. central bank has hiked its policy rate 225 basis points since March. Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s address on Friday at the annual Jackson Hole global central banking conference in Wyoming could shed more light on whether the Fed can engineer an economic slowdown without triggering a recession.

The labor market is a key piece of that puzzle. Though interest rate-sensitive industries like housing and technology are laying off workers, broad-based job cuts have yet to materialize, leaving the overall labor market tight.

A separate report from the Labor Department on Thursday showed initial claims for state unemployment benefits fell 2,000 to a seasonally adjusted 243,000 for the week ended Aug. 20. Claims have been bouncing around the 250,000 level since hitting an eight-month high of 261,000 in mid-July.

The number of people receiving benefits after an initial week of aid dropped 19,000 to 1.415 million during the week ending Aug. 13. The so-called continuing claims, a proxy for hiring, covered the week during which the government surveyed households for August’s unemployment rate.

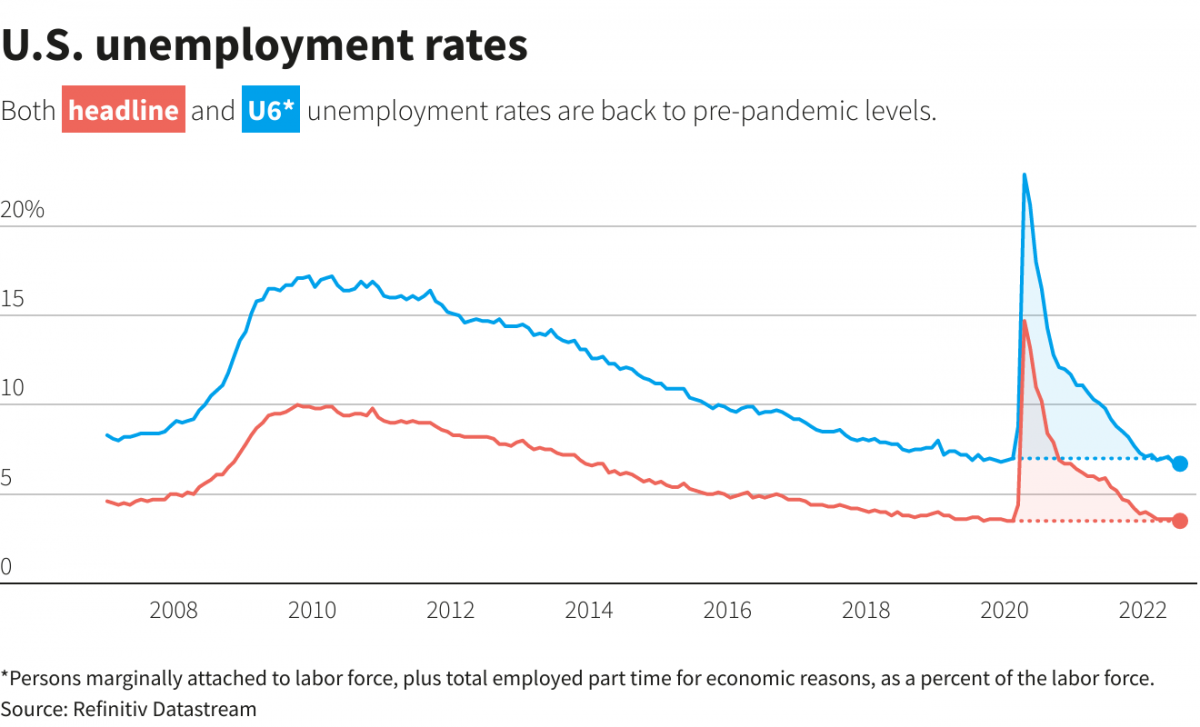

The jobless rate fell to a pre-pandemic low of 3.5% in July from 3.6% in June. There were 10.7 million job openings at the end of June, with 1.8 openings for every unemployed worker.

“The jobs machine will continue to churn, though higher costs, shakier demand and lower profitability will weigh on labor market conditions,” said Oren Klachkin, Lead US Economist at Oxford Economics in New York.

“However, persistently scant labor supply will prevent a spike in jobless claims as employers will be concerned about how long it might take to fill open positions.”