Sometimes the perfect book just happens to find you, ticking all the boxes you want for a review even before you knew those boxes needed ticking. I have been hearing the name Darcie Little Badger echoing around the literary landscape for about two years now since her first novel, Elatsoe, was listed in Time Magazine’s collection of the 100 best fantasy books of all time. Later, I read the Love After the End anthology edited by Joshua Whitehead along with Angela of the Literature Science Alliance which featured her post-climate change apocalyptic short story “Story For a Bottle”.

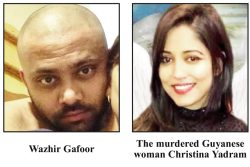

While searching for September’s book, I decided to look for Little Badger, originally intending to review Elatsoe. But then I noticed that she has since published another novel that has been rapidly racking up awards and critical acclaim. That novel was A Snake Falls to Earth.

The title alone made me curious. When I was a child, someone gave me a calendar filled with indigenous stories. The only one I can remember was about a lizard that fell to Earth from the Animal World in the sky. I approached A Snake Falls to Earth from this perspective, curious about what adventures a fallen snake may have on Earth.

What I found was a novel that perfectly encapsulates the central theme for this year’s International Day of the World’s Indigenous People, which was celebrated on August 9th this year. The theme was “The Role of Indigenous Women in the Preservation and Transmission of Traditional Knowledge”. From the first pages, A Snake Falls to Earth features women and girls passing on and preserving their people’s stories. It also centres the ways climate change affects indigenous peoples, their homelands and the animals that live on those lands, and shows how people fight for conservation during climate chaos.

“Esto es importante”

This is important

“Recureda nuestra historia.”

“Remember our history.

– p.3, great-great-grandmother Rosita to Nina, aged 9

A Snake Falls to Earth is a story about how two teenagers and their worlds intersect at the crossroads of conservation and disaster.

Nina’s story begins at her twice-great-grandmother Rosita’s hospital bedside when she’s nine years old. Rosita was once an entertainer who dedicated her life to preserving the Lipan Apache language and stories, even though she confessed to Nina that she carries the sound of their language without the meaning. When Nina visits the ailing Rosita in the hospital, the elder offers Nina one of her last stories, one that she insists is important and needs to be remembered.

But the story is almost lost in translation. Nina only speaks English, but Rosita’s story is a blend of Lipan and Spanish. While Nina does have a translation app on her phone which has helped her bridge the Spanish language barrier between them, the app fails to recognise the Lipan language and thus transcribed a mangled string of nonsense interspersed with a few Spanish phrases: “Homeland/home”, “She was in pain”, “The healer”, “The nightmare”, “Animal People.” What little Nina can understand makes little sense because so much of the context was lost in the poor translation.

After Rosita passes and Nina grows, the story and its mystery haunt her. She spends the next eight years trying to find a way to translate the story while also doing some investigations into her family history and the strangeness that seems to follow them. As soon as Nina feels like she has a grasp on the story’s meaning, a disaster that threatens to erase her hard work and harm her family looms over the horizon.

“I can’t remember when I learned about the path to anywhere-you-please. It’s one of those stories everybody seems to know, like a persistent thread of gossip. But I’ll never forget the day it found me, completely by chance, in the terror of Robin-Kept-Forest”

– p. 7, Oli the Cottonmouth.

Oli is a Cottonmouth, an animal person like those found in Rosita’s stories. He lives in the Reflecting World, a secondary world that’s like Earth but populated by animal people, spirits and monsters. While Nina is spending her time trying to uncover her family history, Oli is doing his best to survive his first days as an independent snake after his mother kicks him out of her cottage. She did do her best to prepare him, packing rations and a good blanket before sending him on his way, but Oli quickly finds himself in trouble. He gets lost on his way, chased by alligator and bird people, and hunted by a monster. Only his wits and good luck save him during that first day on his own.

While trying to retrace his steps to reach his original destination, Oli daydreams about a peaceful home with friendlier neighbours. While dreaming, he accidentally walks on the path to anywhere-you-please, which takes him to a tranquil lakeshore where he ultimately settles in and makes his home.

This bit of luck blossoms into two fruitful years for Oli. His new neighbour, a toad named Ami, is a friendly and amiable companion. He befriends coyote, hawk, bear and mockingbird people and has more pleasant adventures with his new company.

Until disaster strikes and Oli and his friends quickly find that the solution to their problem is somewhere on Earth. So they leave the Reflecting World and head to Earth, where they meet Nina. Now this rag-tag group of human and animal people have to work together to solve their mutual problems while escaping the nightmares that loom over them..

Language Loss and Preservation

I thought that the novel’s opening scene encapsulates the theme for this year’s International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples perfectly, while also raising an issue that many native communities face: language loss.

Throughout the story, we see how women and girls in Nina’s indigenous nation have been working to preserve the stories of their peoples. Rosita dedicated her life to remembering the stories of her people, even though she did not fully understand the language. Nina’s grandmother also kept stories about their family’s strange history alive and ultimately passed that down to her son and granddaughter. Nina’s mother is also a linguist, and she helped her get her translation project started.

In an interview with the Politics and Prose bookstore, Little Badger also showcased noted how young indigenous peoples are using their available technology to build community and to help preserve their stories, culture, ways of life, and fight for their rights and land. I loved this inclusion and the way that Little Badger shows that not everyone using technology to preserve their stories is in it for the views. Some are doing it quietly, the way Nina uses her St0ryt1ller app. While she keeps most of her stories private, she uses the app to record what she remembers of Rosita’s stories and document her theories about her family history. Her journey throughout the stories reminds me of the indigenous TikTokers who have been showcasing their art, culture, humour and history on the platform, thus uplifting their ancestor’s stories and contributions to their societies while also creating a sort of open-source archive for all members of their communities to access.

There are similar projects happening here in Guyana as well. For example, Athena Harding and Dr Adrian Gomes’ work to preserve and revive the Carib and Wapishana languages come to mind. The Ministry of Amerindian Affairs also dedicated a part of its 2022 budget to preserving our indigenous languages. If anything, Little Badger’s novel and her references to the Lipan Apache nation’s work show that such preservation is possible and that we should support our fellow Guyanese’s efforts in this endeavour.

Climate Change and Species Conservation

The second theme that threads throughout the story is about the consequences of colonialism and climate change on animal populations. Little Badger shows us these effects through the animal people in the story. Little Badger explained in the Politics and Prose interview that animal people are a feature of the Lipan Apache stories she heard and loved while growing up. Throughout the novel, she speculates about how the animal people in the Reflecting World are being affected by anthropogenic climate change.

Through Oli’s adventures and stories, we see that when animals are doing well on Earth, their corresponding animal people communities do well in The Reflecting World. During his journeys, he encounters many kinds of animal people, and also learns about more about them from his elders.

One of the stories he learned about from his grandmother was about the collapse of the Bison people’s civilisation. When his grandmother was a girl, the Bison people were plentiful and used to have a thriving city. A sudden plague devastated the Bison people, and very much like Oli and his friends, a group of adventurers went to Earth to find the cause of the catastrophe. There, they discovered that the Bison were going extinct because of the deliberate overhunting by American colonisers to eradicate the native populations that depended on the bison for their livelihoods.

One of the stories he learned about from his grandmother was about the collapse of the Bison people’s civilisation. When his grandmother was a girl, the Bison people were plentiful and used to have a thriving city. A sudden plague devastated the Bison people, and very much like Oli and his friends, a group of adventurers went to Earth to find the cause of the catastrophe. There, they discovered that the Bison were going extinct because of the deliberate overhunting by American colonisers to eradicate the native populations that depended on the bison for their livelihoods.

However, not all animals go extinct because of direct human action. Others struggle to stay alive because of the effects of climate change: hurricanes and droughts causing causing habitat loss or unfavourable conditions for vulnerable animals. We see how conservation efforts have been helping to keep some of the animal peoples alive, like the wolf people Oli meets on the way to Earth. But sometimes even the best conservation efforts can fail because of climate disasters, which directly affect some of the animal people Oli cares about.

Oli’s determination to battle extinction is admirable, and turns A Snake Falls to Earth into a hopeful dystopia. By the end of the novel, we see the impacts of climate change and gentrification on both Nina and her family and Oli’s rag-tag group of animal people. But we also see how small groups of young people who are passionate about making a difference in the world to save themselves and their friends can mean the difference between life and death for individuals or small groups. In that way, they can change the world, even if it’s just making it a better place for a small group.

I loved A Snake Falls to Earth. The book was funny and heart-warming and delightfully fantastical. By the end, I was deeply invested in Oli and Nina’s individual and joint stories. Little Badger admits that this novel is a near-future extrapolation of what the world will be like if our ongoing climate crisis remains unchecked, showing us a dystopia filled with violent weather phenomena.

But she also paints this dystopia with hope, showing her readers how young people can use technology and build communities around making small pockets of change that ultimately amalgamate into more significant changes.

I highly recommend this to anyone who wants to read more indigenous fiction. I also hope to see more novels like these being produced by our own indigenous communities, stories that blend their modern lives with ancestral stories. And to my readers, if you get the chance, check out the Amerindian Heritage Month schedule and support our indigenous artisans, artists, creators and scholars. They’re representing their cultures and making waves in our country, just like Nina and Oli.

Want to learn more about Darcie Little Badger? Check out her Author Website. It lists all of her stories, including Elatsoe and the dozens of short stories she has written over the decade.

Want to read more work by indigenous authors? Check out these books:

Love After the End edited by Joshua Whitehead

Robopocalypse by Daniel H. Wilson

Black Sun by Rebecca Roan Horse

The Only Good Indians by Stephan Graham Jones

A Map to the Sun by Sloane Leone