Introduction

Last week’s column used the World Bank’s systematic country diagnostic, SCD, of Guyana, to unravel the embedded obstacles to the country’s lack of inclusive development along with the grim persistence of poverty up to the advent of its windfall oil finds in 2015. Prescriptive solutions are offered in the Report, but before I address the prescriptions from the perspective of embedded poverty, I must first expand on the linkage between the SCD-type driven initiatives and the global framework of development goals. Consider that, on the World Bank’s Website, it unabashedly proclaims that, “it is committed to helping achieve the Millennium Development Goals, MDGs because, simply put, these goals are our goals.”

Millennium Development Goals, MDGs 2000-2015

On its Website the United Nations simply announces as follows; eight MDGs, ranging from halving extreme poverty rates to halting the spread of the HIV/AIDS virus and providing universal primary education by the target date of 2015 – constitute a globally agreed program of all United Nations Members as well as the world’s leading development institutions. Together they have galvanized unprecedented all-round efforts to meet the needs and hopes of the world’s poorest.

Further, the United Nations declares it is also working in tandem with governments, civil society, academia, and other partners to build on the momentum generated by the MDGs over the period 2000 to 2015; and carry on with an ambitious post-2015 development agenda. That is the Sustainable Development Goals, SDGs, 2015-30

Sustainable Development Goals, SDGs, 2015-2030

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which followed the MDGs are often abbreviated and referred to as the Global Goals after they were adopted by the United Nations in 2015 following the scheduled termination of the MDGs. In their essence the SDGs constitute a universal call by all Members of the United Nations to coordinate their actions to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that by 2030 all people enjoy peace and prosperity. In sum this is their governing rubric.

The 17 SDGs are systemically integrated based on the full recognition that action in one area will affect outcomes in others. And that development requires a balance of social, economic, as well as environmental sustainability.

Under the rubric of the SDGs countries have fully committed to prioritize progress for those who remain furthest behind. The SDGs are explicitly designed to end poverty, hunger, AIDS, and discrimination against women and girls.

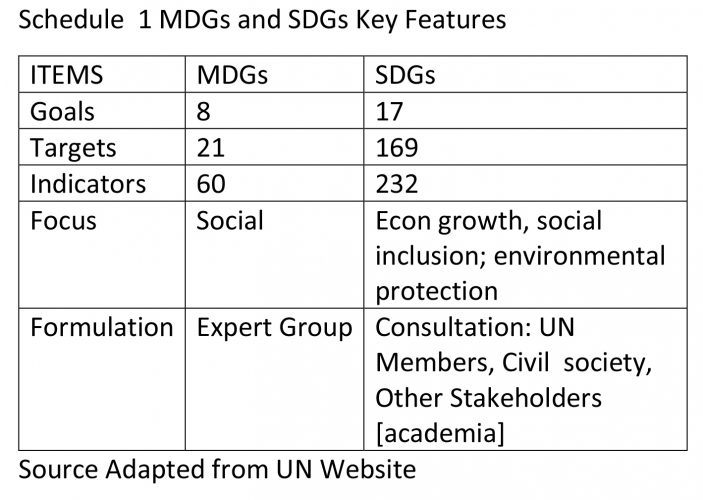

The key metrics of the SDGs are that, creativity, knowhow, technology and financial resources from all of society is necessary to achieve the SDGs in every context. An immediate query to ponder upfront is how do the MDGs and SDGs compare?

Comparators

The SDGs were designed to build on the successes of the MDGs, which embody a number of specified targets and milestones in eliminating extreme poverty and relatedly, the worst forms of human deprivation. Indeed, the SDGs expanded its scope to 17 goals from the eight (8) goals in the MDGs, which covers universal goals on fighting inequalities, increasing economic growth, providing decent jobs, sustainable cities and human settlements, industrialization, tackling ecosystems, oceans, climate change, sustainable consumption and production as well as building peace and strengthening justice and institutions. Unlike the MDGs, which only target the developing countries. More ambitiously, the SDGs apply to all countries whether rich, middle income or poor. The SDGs are also nationally-owned and country-led, wherein each country is given the freedom to establish a national framework in achieving the SDGs.

The Schedule below highlights the key elements of the above text.

The Hunan Development Report

It is important to observe an overlap in the growing understanding of poverty and development and their measurement. This is exemplified in the production of UNDP’s annual Human Development Reports (HDRs). These have been released most years since 1990 and “have explored different themes through a human development approach; thereby having had an extensive influence on development debates worldwide.”

Because the reports are produced by the Human Development Report Office for the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), on its Website the UNDP asserts this ensures its editorial independence!

Importantly, the HDR reports on a Human Development Index (HDI), which is a “summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, being knowledgeable and having a decent standard of living.” Indeed the HDI is the geometric mean of normalized indices for each of the three dimensions.

The Website admits the HDI “simplifies and captures only part of what human development entails”; acknowledging it does not capture adequately poverty, inequality, human security, empowerment, and so on. The Report provides related composite indices as broader proxies on key aspects of human development.

Conclusion

Guyana’s HDI value for the last pre-pandemic year, 2019, is 0.682— which places the country in the medium human development category; ranking 122 out of 189 countries and territories. Between 1990 and 2019, Guyana’s HDI value increased from 0.548 to 0.682, an increase of 24.5 percent. Guyana’s progress in each of the HDI indicators reveals that, between 1990 and 2019, life expectancy at birth increased by 6.6 years, mean years of schooling increased by 1.7 years and expected years of schooling increased by 1.3 years. Guyana’s GNI per capita increased by about 272.6 percent between 1990 and 2019

Next week I wrap-up by noting the Guyana SDC’s prescriptions which address cash transfers.