By Ronald M Austin

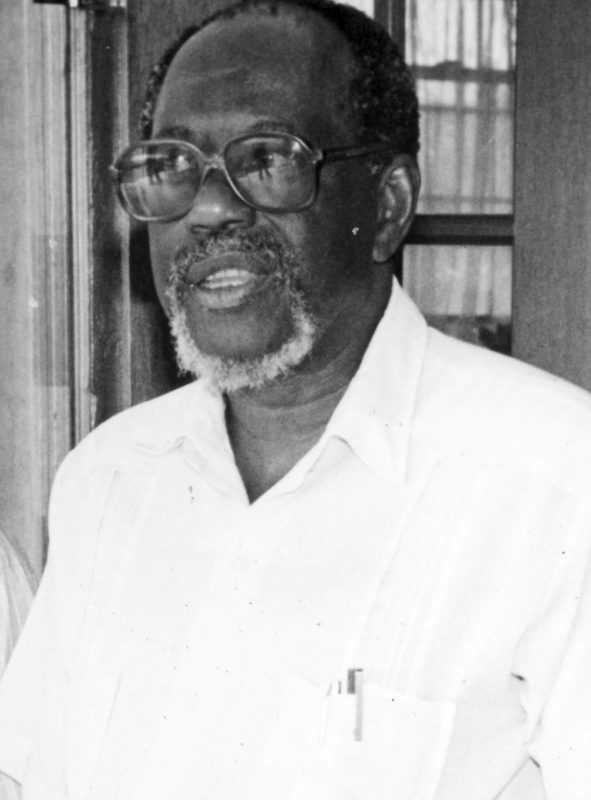

The man who died on September 1, 2022, at the age of 92, was an exceptional human being. Rashleigh Esmond Jackson was a well-educated, articulate man, who had a puckish sense of humour, an infectious sense of fun and an unfailing interest in anything which improved the mind. He was interested in jazz and classical music, literature, art, the varieties of education and the importance of sports in society. It was not surprising, therefore, that when he turned his mind to diplomacy he not only mastered this art but ensured that its strengths and possibilities were pressed into service to ensure the survival of the country he loved. His belief in the need for an equitable international system as well his commitment to Caribbean and Regional integration, his diplomatic network spanning several continents were marshaled in defence of his country. By the time Rashleigh Jackson resigned as Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1990, after a tenure of approximately twelve years, he had helped bring the state of Guyana safely to port, having helped to protect it from the aggressive wiles of Venezuela and Suriname and those who initially opposed its ideological direction. Incidentally, his tenure was the second longest in the Western hemisphere after that of Malmierca of Cuba.

The American Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, a man with no pretense to modesty, entitled his memoirs “Present at the Creation.” But he did not actually put in place the building blocks of American diplomacy. Rashleigh Jackson, a more modest man, if ever he had intended to write his memoirs, would have had a greater claim to have been present at the creation of Guyana’s Foreign Policy.

Jackson joined the newly created Department of External Affairs in 1964 from Queen’s College. This department became a fully-fledged Ministry of External Affairs and subsequently the Ministry of Foreign Affairs when Guyana became independent in 1966. Jackson replaced Neville Selman as the Permanent Secretary in 1968, when the latter departed for duties as High Commissioner to Canada. It may be of historical interest to know that this Selman played a role in the recognition of Cuba in 1972. The then Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Linden Forbes Samson Burnham, for reasons which he has taken to the grave, conducted the negotiations to recognize the Republic of Cuba through our High Commission in Ottawa.

This was a time of creating a diplomatic institution for which there was no model in Guyana, as the colonial authority exercised complete control over the conduct of the country’s external relations. The first order of business was the training of a corps of recruits and the devising of an appropriate structure to reflect Guyana’s foreign policy interests. Jackson, as Sir Shridath Ramphal has recently recorded, was a vital part of this exercise, even as he himself attended programmes of diplomatic training in the United States and the Caribbean. With assistance from countries such as Canada (our early diplomats were attached to Canadian Missions for training) and Britain, which held several training programmes here, the recently independent Guyana was able to create a group of outstanding young diplomats in a very short period of time. There was an important innovation which must be noted. Mr. Burnham, in his capacity of Minister of Foreign Affairs, in 1968, instructed that at regular intervals Heads of Mission must meet to assess, analyse and review information within their purview with a view to refining and improving the nation’s foreign policy. This mechanism for foreign policy analysis and implementation has lasted.

An important point must be made here as it is of vital national interest. In the creation of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, adherence to the social beliefs and ideals of nation was not overlooked. It was in this environment that Officers such as Willie Jugdeo, George Fraser, Ralph Chandisingh, Harold Sahadeo, Rita Ramlall, Vic Persaud, Jamolodeen, Patrick Pahalan, and Altaf Mohammed and many others were given the opportunity to participate in the implementation of Guyana’s foreign policy.

But the structural building and training had to be tethered to a foreign policy. Rashleigh Jackson has told me that he had initially submitted a Paper (he shared a copy with me) to the requisite authorities recommending that Guyana adopt a policy of non-Alignment. There was skepticism except from Forbes Burnham and Eusi Kwayana. Rashleigh Jackson, Forbes Burnham and later Sonny Ramphal, and others, then set about making Non-Alignment the foundation of the nation’s foreign policy. Also, the concept of multilateralism was added to the foundational principle of non-alignment. As a consequence, Guyana became a Non-Aligned state by 1970 when it joined the Movement in Lusaka, Zambia. Previously, it had entered the UN and the Commonwealth. The success of the training received and the organizational skills and sense of purpose of our fledgling diplomats ensured that Guyana hosted the first Foreign Minister’s conference of Non-Aligned states in the Western hemisphere. The success of this conference is beyond dispute. Of its many decisions those which focused on the need for a national liberation, especially in Africa, the imperative for a more just international system, and the fight for an equitable economic system stood out. Jackson was the Secretary General of the Secretariat, which prepared and planned for this conference.

The decade of the seventies was a tumultuous one. It was characterized by the fierce ideological rivalry between the super powers, the intensification of the African liberation struggles, major eruptions in the Middle East in 1973, including the oil embargo, the assertion of the rights of small states and the transformational issues of women’s rights and the environment. This was a hostile environment for small and emerging states. Jackson’s appointment as Permanent Representative to the UN was therefore a felicitous one.This was a fulfillment of a lifelong ambition and he proceeded to acquire an intimate understanding of the United Nations and its system and it released its creative energies. Eventually, he was able to use the institutional and political strengths of the United Nations as a protective shield for his country.

I first met him in 1973 when I was fortunate to be selected to be a member of the Guyana delegation to the world body. He was friendly, articulate, and in full command of the Permanent Mission, which he ran efficiently along with Miles Stoby, his Deputy. What immediately struck me was how Jackson’s training in mathematics aided his diplomatic skills. I was fascinated by his analytical ability at staff meetings. There he would sum up a discussion by resolving pressing international issues into their individual elements and then reach impressive and well-thought-out conclusions. We therefore all went to our several committees with clear ideas as to how we could pursue the nation’s business. I also saw Jackson in his intellectual pomp. Cigar in hand, he would edit a draft speech with consummate ease. I picked up the Jacksonian locutions: “inbetweenities”, “chapeau paragraphs”, “internal consistencies” and many more which now escape my memory. And he was not afraid to allow a young diplomatic to grow. Although I was at a very young age and inexperienced in the wiles of diplomacy, Jackson made it possible for me to be present when Foreign Minister, SS Ramphal, drafted his General Assembly speeches or when he met such celebrated diplomats as Francois Poncet of France or some of the Latin American heavyweights. More than this, he appeared to be a strategist, deploying the considerable talents of Dr Denis Benn, Joe Saunders, Dr Barton Scotland, and Lloyd Searwar to important UN committees in successful pursuit of Guyana’s foreign policy goals.

There was definite and measurable success: the adoption of the 1981 resolution by the UN on the inadmissibility of the use of force; the passage of the resolution on Economic Cooperation Among Developing Countries; Guyana’s election to the Security Council on two occasions ( on the second, possibly a diplomatic first, Guyana was not even a candidate); the nation’s election to ECOSOC; and the many resolutions which Guyana co-sponsored on a variety of subjects. For Jackson there were some personal and particular triumph: he chaired the Security Council and he was instrumental in getting vital resolutions passed affecting the destinies of such countries as Namibia and Belize. He also became the President of the Council for Namibia, effectively becoming a Head of State. His respected standing as an admired diplomat was unquestioned.

But what were the last lessons I learnt from my time with Jackson at the UN? A diplomatic network is essential for diplomats. He gave expression to his own advice. In mastering multilateral diplomacy, he had acquired a vast diplomatic network which included Kofi Anan, Malimierca and Ricardo Alarcon of Cuba, Salim Abdul Salim of Tanzania, Perez de Cuellar, Abdelaziz Bouteflika and Rahal of Algeria, and a tall, elegant diplomat with an equally elegant beard called Fall of Senegal. The latter fascinated me by his dignity and regal manners. Then, too there was Ricky Jaipal of India. He was soft spoken and refined. He drew cartoons while garrulous diplomats prosed on. He shared some of these drawings with Jackson. On several occasions, Jackson used this network to get resolutions through the General Assembly and more particularly when our foreign policy needed a nudge after he left office. But the most important fact I learnt is that small nations do have influence and diplomatic power. No nation, large or small, could proceed with a resolution or an important matter without knowing the disposition of Jackson and the network that supported him. I learnt, too, the importance of negotiations, of which Jackson was an acknowledged master. I found out that negotiations could only be successful if some effort is made to understand the motivations of one’s opponent. Additionally, Jackson would tell you that diplomacy was hard work that sometimes did not bear immediate results. Also, the foreign policy of the nation was an extension of its national policy. I doubt whether I could have learnt these things in any Academy.

Rashleigh Jackson became Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1978, after the dismissal of Fred Wills. I have always been intrigued by this development. No other country that I know of has been fortunate enough to have had such a succession of brilliant minds as Foreign Ministers as Ramphal, Wills and Jackson. And each came from the same form at Queen’s College. Each Foreign Minister also handed his successor an adequate machinery and corps of officers who could effectively continue the pursuit of the nation’s foreign policy. Jackson’s tenure has been partly recorded in his book, Guyana’s Diplomacy (2003), and in the extended interview he conducted with Dr Sue Onslow of the Institute of Commonwealth studies in 2015. I can only attempt to add to what he has already described.

On becoming Foreign Minister Rashleigh Jackson faced a slew of critical problems, both internal and external. I will not burden the text with a surfeit of details of these critical problems but will focus on what I consider to be the most important of them. These threatened the foundation of the state.

At the beginning of the eighties the world was in ideological transition. As a result, Guyana faced an aggressive western world and their international financial institutions. Their clear intent was to reverse the ideological aspect of the Guyanese state. Only those present will know the resulting anxiety and exhaustion as the Ministry sought to buttress the efforts of then government to combat this nefarious exercise. As if this were not enough, the invasion of Grenada in 1983 was as shocking as it was shattering. Its ideological dimension was not lost on any of us. Jackson, stoical as he was, was clearly shocked by this development and the destruction of the doctrine of ideological pluralism, which he so earnestly embraced.

Yet the greatest challenge resulted from Venezuela’s repudiation of the Protocol of Port of Spain in 1981. It fell to Jackson to formulate, along with his other colleagues in Government, the plan to work towards the establishment of the Good Officer process, which stabilized relations with Venezuela, and which lasted until 2015. The very patience which Jackson counseled, and a careful reading and understanding of the prevailing international environment, paid off when the international situation was transformed after the fall of the Berlin and new opportunities were presented for Guyana to adjust, and realign its foreign policy in its national interest.

Ronald M Austin is a former Guyana Ambassador to the People’s Republic of China