In a previous analysis of the Caribbean Festival of the Arts (Carifesta) reasons were elucidated as to why on the 50th anniversary of this grand historic event, instead of celebratory glory, there were so many critical questions. It is important to focus on the artistic progress of Carifesta since its inauguration in Guyana in 1972, and the state of the festival as an exhibition of the arts of the Caribbean. How has it served the territories? How has it served the advancement of the arts?

In a previous analysis of the Caribbean Festival of the Arts (Carifesta) reasons were elucidated as to why on the 50th anniversary of this grand historic event, instead of celebratory glory, there were so many critical questions. It is important to focus on the artistic progress of Carifesta since its inauguration in Guyana in 1972, and the state of the festival as an exhibition of the arts of the Caribbean. How has it served the territories? How has it served the advancement of the arts?

Jamaican novelist Andrew Salkey has provided the most comprehensive coverage of the conferences in Georgetown, Guyana (1966 and 1970) during which Carifesta was created in Georgetown Journal: A Caribbean Writer’s Journey from London via Port of Spain to Georgetown Guyana 1970 (London, 1971). He was able to capture the intentions, concepts and collective mind of the artists who outlined what the festival should look like, what it should represent and what it should do for the regional arts. We can, therefore, measure Carifesta’s accomplishments against that blueprint and see whether it has made any impact on the arts in the West Indies.

Salkey focused on most of the major players in the meetings, including Martin Carter, who was Guyana’s minister of culture at the time, and poet A J Seymour who was the main rapporteur and a major architect in defining the arts. Interactions with many of the visiting participants such as Jamaican painter Karl Parboosingh, and Trinidadian writers Sam Selvon and John La Rose, pointed in the direction of what they thought a regional festival ought to achieve. Salkey, and other invitees to those meetings, were able to bring to the table the kind of work already in progress in the Caribbean Artist Movement (CAM) that flourished in London between 1966 and 1972. It was founded by Kamau Brathwaite and included Salkey, La Rose and a number of others.

CAM is regarded as a forerunner to Carifesta and described as “the first organised collaboration of artists from the Caribbean with the aim of celebrating a new sense of shared Caribbean ‘nationhood’, exchanging ideas and attempting to forge a new Caribbean aesthetic in the arts”. There were previous efforts such as a smaller, similar movement in London which was responsible for the premiere production of the historical play about the Haitian revolution, The Black Jacobins, in 1953; and the opening of the West Indian Federation in 1960 which produced a similar historical drama Drums and Colours by Derek Walcott.

These efforts were eventually realised in literature, according to the specifications outlined for the first Carifesta. Each festival was to produce an anthology of writing from participating territories in order to keep pace with Caribbean literature over the years, and it was a particular ideological statement that the literature of the Dutch, French and Hispanic Caribbean should be included. These anthologies would serve as permanent records of an otherwise fleeting event and enhance publication of West Indian literature.

The most substantial record of the literature was the first – New Writing in the Caribbean: Carifesta 1972, a collection edited by Seymour which effectively introduced Surinamese and other literature from non-English territories to a wider Anglophone audience. But Guyana produced two volumes because in 1973, Volume 11 of Kaie, the journal of the national History and Arts Council, which was turned into the Department of Culture, published “The Literary Vision of Carifesta 1972” edited by Lynette Dolphin. This was appropriately titled because it reflected exactly what the framers of Carifesta had in mind as far as their promotion of the literature of the wider multi-lingual region is concerned.

This continued in Carifesta II in Kingston, which also produced two substantial literary volumes. The only one dedicated exclusively to prose writing was itself a formidable collection of 248 pages – Carifesta Forum: An Anthology of 20 Caribbean Voices, edited by Jamaican novelist John Hearne. This, too, fit very well the criterion of a permanent record of sundry pieces of prose writing all in one volume as an exhibition of the writing up to 1976. Its companion anthology was a collection of plays – A Time and A Season: 8 Caribbean Plays (1972) edited by West Indian dramatist Errol Hill of Trinidad. This was a timely anthology which included some of the new plays yet unpublished in print such as The Banjo Man by Roderick Walcott (St Lucia) and The Tramping Man by Ian McDonald (Guyana) along with James’ classic Black Jacobins and others that advanced the documentation of regional drama.

The fifth and last publication was an Anthology of Carifesta Poetry edited by Petamber Persaud for Carifesta X in Guyana in 2008. This does not strictly reflect the poetry presented in the festival itself, but can give an indication of the work of poets from the territories that participated. The sum total of these suggest that Carifesta has fallen short in this promise of a continuing series that could track the literature from year to year. They are valuable documents, but for the intended purpose, insufficient.

One could argue that literature was also to be well served by the Carifesta Symposia – statutory presentations on the festival agenda. These attracted leading critics and literary personalities in the past, but seem to have changed track and diminished. The power of conference-type discourse on West Indian literature that took place in Jamaica at Carifesta II was evident in such contributions as Edward Baugh’s “The West Indian Novelist and His Quarrel With History” and Martin Carter’s position on “Exile” was not often repeated. There was similar richness in Trinidad in both 1992 and 1995, Guyana in 2008, and Barbados in 2017. Barbados covered good ground, including a few of the high-flying Caribbean writers, while Guyana had a thoroughly designed series on literature as well as the fine arts, testimonies of writers and Caribbean philosophical thought. Derek Walcott was the main guest writer and it was at that symposium that he had his famous debate with then president Bharrat Jagdeo of Guyana. Other prominent guests included David Dabydeen, Earl Lovelace, Austin Clarke and Baugh.

But the symposia waned or became redeployed and those foregoing examples now stand as pockets of power in a diluted series. One of the reasons for the decline of literary Carifesta Symposia could perhaps be the sporadic nature of the festival, coupled with the development of new conferences that began to command the attention of academics.

One can claim that the Caricom Secretariat sometimes commandeered the symposia for good reason. One such was in 2003 in Suriname when it was turned over to introspection; the state of the festival was examined and found wanting and it was in that forum that it was decided to “Reinvent Carifesta”. Another occasion was in 2013 in Suriname again, when the symposium was diverted into a Youth Forum which put into effect a Carifesta focus on youth and the creation of opportunities for youth development. In 2013, attention was paid to professional music and the exposure of talented youth to international scouts from Europe. Since then each country has been asked to include youth in their delegations.

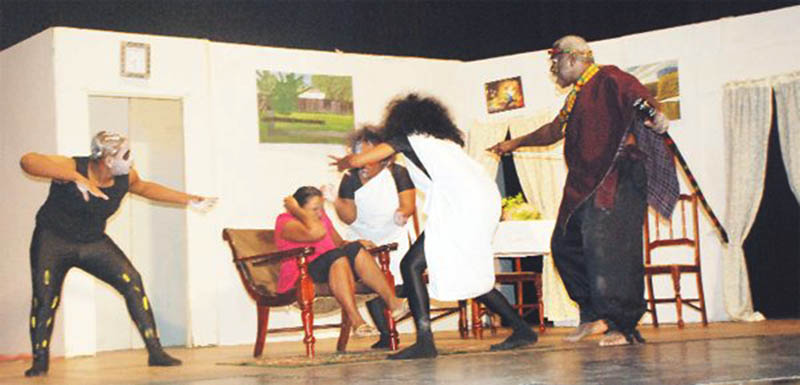

One important area that experienced not so much fluctuation as the symposia, but declined, is drama. The first attempts at regional collaboration seemed to have had drama at their centre, as in London 1953 and in Trinidad in 1960. Famous plays were premiered in Guyana in 1972, such as Couvade – A Dream Play of Guyana by Michael Gilkes. Carifesta was held as the place to see the major and best West Indian plays. That was the case in Jamaica which featured Walcott’s Oh Babylon (1976) and the fascinating rise of the Guyanese performing act “Dem Two”. There were also major plays like Maskarade (1979) by Sylvia Wynter and Jim Nelson and Dennis Scott’s An Echo in the Bone (1974). But the last appearance of a leading national play as a routine in Carifesta for 13 years was David Heron’s Ecstasy, directed by Trevor Nairne, which represented Jamaica in the festival in Trinidad in 1995.

Ecstasy marked a new brand of popular theatre developed in Jamaica with the rise of the professional theatre there, and was worth seeing as a representative of the best of the region. This was followed by a period of drought. However, plays were performed at the same time as Carifesta, including Mary Could Dance by Richard Raghubansie, in Trinidad in 2006. This play could be seen on the fringe in Port-of-Spain but it was an unofficial performance and not part of Carifesta. In 2008, Artistic Director of Carifesta X Paloma Mohamed, herself a dramatist with a vision for theatre in the festival, deliberately invited major full-length plays and quite a few territories responded. These included Trinidad and Tobago that premiered Rawle Gibbons’ Ogun Iyan–As in Pan, an important brand of Caribbean theatre. This was matched by Guyana’s Legend of the Silk Cotton Tree, a story and concept by Barry Braithwaite and play script by myself; and from Jamaica River Bottom by Oliver Samuels and Love Games by Patrick Brown. Among other countries sending top plays were the Cayman Islands and St Lucia.

Such plays disappeared again until 2019. A number of factors were responsible for this decline. One has to do with the entrenchment of professional theatre in the West Indies, which made it more complicated for a country to send professional plays to represent it in Carifesta. Conditions would be vastly different from the case of an amateur play. Besides, restrictions began to appear in Carifesta because of programme overload. Countries were restricting the length of plays. Participating territories were told plays had to fit within a maximum playing time of one hour. Interestingly, while Trinidad issued that restriction in 2019, Carifesta still benefited from the performance of Efebo Wilkinson’s full-length drama Bitter Cassava. The festival was much richer for including that play, but it seemed Trinidadian drama was exempt from the stifling restrictions.

Complementary to those restrictions was the introduction of “Country Night” in which each country presents a kind of composite theatre performance representing its performing arts. Gradually these seem to have replaced full length plays totally in Carifesta. In 2015 (Haiti), countries were advised not to bring plays (performed in English) because of the language barrier.

In a number of ways, therefore, Carifesta waned as a place where the best of the arts in the various territories of the Caribbean could be seen.

There are other reasons why this opportunity has ceased in the festival, and why the best acts no longer see it as important. But these, as well as Carifesta for the middle class and the popularisation of the festival; overcrowding of performances and the breakdown of artistic exchanges; the state of fine arts, dance, music and the cultural industries, including crafts, the culinary arts and the popularity of the “Grand Market” will need to be analysed in a separate instalment.