Even as it reels from United States sanctions that have limited its revenue from oil exports, Venezuela, believed to have the world’s largest oil reserves, is beginning to send signals that it is taking halting steps towards resuming its place in the global oil and gas industry pecking order.

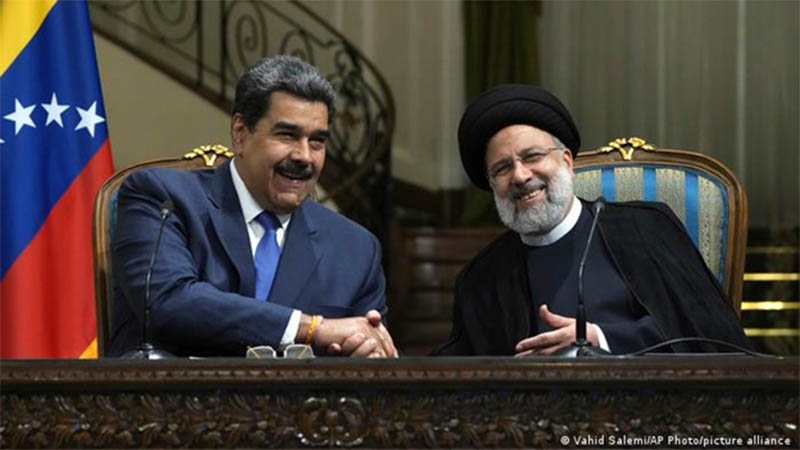

“Venezuela is ready and willing to fulfil its role and supply, in a stable and secure manner, the oil and gas market that the world economy needs,” its President Nicholas Maduro was quoted as saying earlier this month. His administration had announced that it was in the process of striking a deal with Iran to step up its oil refining capacity.

There are two significant things about President Maduro’s declaration. First, it appears to ignore the fact that the United States is yet to call off its protracted sanctions squeeze that has seriously staunched the flow of Venezuelan oil exports. Second, the timing of Maduro’s declaration coincides with global oil supply jitters linked to the current hostilities between Russia and Ukraine. There are signs that Russian President Vladimir Putin is prepared to use his country’s enormous oil reserves as a weapon in its extended war with the west which has come down on the side of Ukraine in the conflict.

In a September 19 oilprice.com article, Felicity Bradstock amplified Maduro’s claim that while hopes have been dashed that the US sanctions might have, by now, been lifted, a global shift in circumstances arising out of the Russia-Ukraine war better positions Venezuela to begin to make a meaningful mark again on the global oil and gas industry. “Venezuela’s statement to the world is clear – it is ready to pump and export huge amounts of its crude whenever given the chance,” Bradstock wrote. The extant circumstances, specifically the oil supply jitters deriving from the Russia-Ukraine conflict, means that (in cricketing parlance) Venezuela is batting on a decidedly better wicket.

Having seen the rejection of its sustained lobby for the US to allow Venezuelan oil to fill the gap created by the widespread global sanctions on Russian energy, it now appears that Caracas is prepared to go over the head of Washington in an effort to get back into the global oil supply game big time. The view that Venezuela’s oil sector might be so rundown as to cause it not to possess the capacity to keep its president’s promise, can be afforded a two-fold response. First, Venezuela can point to the support for its oil recovery and its refining capability that has been forthcoming from Iran. The second point, a much more obvious one, is that the oil supply crisis arising out of the situation in the Ukraine, means that Venezuela, with its enormous reserves, is more than well-positioned to fill such breaches as might arise, going forward.

That said, as Bradstock pointed out, Venezuela’s claim must be weighed against concerns that its oil industry was still “far from recovering, after years of low production and underinvestment”. Nevertheless, Maduro evidently sees the prevailing threat to global supply as a golden opportunity to salvage his country’s oil industry that had previously contributed all but around 4% of the country’s income. Simultaneously, there were circumstances that would appear to have had the effect of loosening the grip that the US had on Venezuelan oil exports under the Trump administration. According to Bradstock, back in May this year, President Biden had “made some concessions to the sanctions” that allowed for Venezuela to export oil to Europe for debt, “The Italian firm Eni and the Spanish oil major, Repsol, were allowed to ship Venezuelan crude to Europe in an oil-for-debt swap,” she wrote. If this amounted to a proverbial drop in the ocean when set against the reality of the economic crisis facing Venezuela, the Maduro administration no doubt regarded the development as a modest but, nonetheless, welcome loosening of the stranglehold the US had imposed on the country. As Bradstock put it, the Eni and Repsol developments served to provide “greater optimism for more concessions to be made in the coming months.” In August, Maduro decided to suspend oil-for-debt shipments to Europe, stating, as Bradstock wrote, that he wanted “refined fuels from Eni and Repsol in exchange for crude in place of the current deal.” Given the recent difficulty it encountered in securing refined oil, its trade in crude oil for condensate with Iran notwithstanding, the simple truth, Bradstock wrote was that “if Venezuela can import more refined oils, it could better support its oil industry’s recovery,” since much of its oil production operations require diluents to continue.

It is the sheer size of Venezuela’s oil reserves that keeps the country in the game and holds out hope that its position will become stronger as long as the Russia-Ukraine conflict and its knock-on consequences for global oil supplies persist. What cannot be ruled out, Bradstock wrote, is the “political uncertainty,” that has “deterred many oil companies from investing in the region, despite the abundance of reserves.” Still, the continued perceived viability of Venezuela’s oil industry is reflected in the fact that “currently, US oil major Chevron, Italy’s Eni, and Spain’s Repsol continue to operate in the country, with others” even as other companies, including ExxonMobil, appear to have called it a day as far as Venezuela’s oil industry is concerned.

As Bradstock correctly pointed out, the issue of the yawning ideological gap between the Maduro administration in Caracas and Washington does not help. All too frequently, one gets the impression that ideology trumps pragmatism and that it is this, as much as anything else, that has kept the US sanctions in place.

Unsurprisingly, as implications for future global oil supplies arise, pragmatists are beginning to look at what was described by Bradstock as the lesser of two evils, which revolves around whether sanctions on Venezuela should be eased to reduce the burden Europe and North America felt due to the loss of Russian oil supplies. However, she noted, “Venezuela’s close political connection with Cuba, China, and Russia has led many to be more critical of this option.” In effect, both the question of the normalisation of Venezuela’s petroleum relations with the west as well as the overarching issue of the immediate-term future of global oil supplies are stuck in the realm of important but still unanswered questions.