Wole Soyinka’s Nigerian play “Death and the King’s Horseman” is easily remembered as one of the essential works of late 20th century African drama. Soyinka’s play is a scathing postcolonial critique and a great example of contemporary approaches to tragedy. Yet, in the decades since its 1975 premiere the acclaim for Soyinka’s play – like with many of his contemporaries – has not translated to other artistic forms.

In American and European cinema, celebrated contemporary works – whether that of 20th century maestros of drama like August Wilson, Tennessee Williams or the novels of Toni Morrison or Ernest Hemingway (or venturing further back a century earlier to the likes of Jane Austen, Henry James, and Oscar Wilde) – film has been a ferocious and valuable consecrator of literary traditions. With adaptations, whether feature films, extended miniseries or tv-movies, literary works have attained new significant value. But it has not been so with the African tradition as so many great African works remain confined to the literary form. Western cinema ignores them, and African cinema struggles to retain the funding for them.

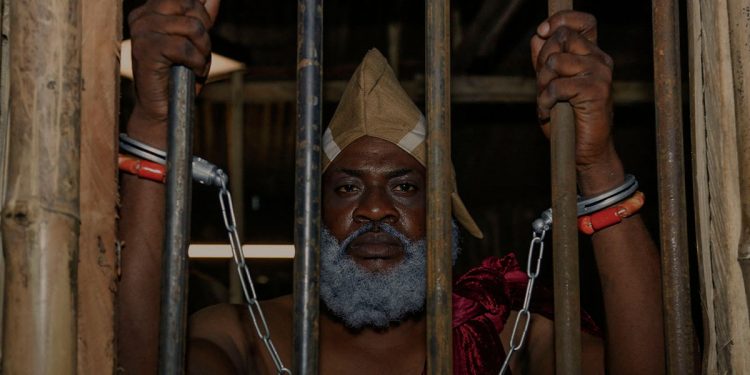

Nigerian director Biyi Bandele’s new film, an adaptation of Soyinka’s play now merely titled, “The King’s Horseman”, comes to the screen slightly weighed by that reality. It is a rare work of African cinema that looks back to the literary traditions of the region. The rights for the play were acquired a decade ago, and at its world-premiere at the Toronto International Festival (TIFF) producer Mo Abudu spoke of the elapsing time as the rights were set to expire. It is as if Bandale felt this urgency in the film, which is retained throughout its proceedings, running at a brief 96 minutes. The film’s set-up is simple: in Yoruba tradition, a few weeks after a King’s death should see the horseman who survived him committing ritual suicide. The horseman’s spirit, as well as those of the king’s horse and dog (also killed in the ceremony), must accompany the dead king’s spirit to the afterlife, otherwise, tradition is ruptured and chaos looms. Elisin Oba, the celebrated horseman, is enjoying his final day on earth when he wavers from his duty to lasciviously allow himself a sexual dalliance with a new bride on his last day on earth. The community allows him his final wish, but the brief dalliance sets a chain of calamity in motion. And, suddenly, the certainty of tradition becomes exposed and vulnerable. There is a lot at stake here.

But, even as Bandale feels acutely aware of the stakes, “The King’s Horseman” announces its commitment to forging its own path. Soyinka’s play was written while he was stationed in Cambridge during a political exile from Nigeria. Like with many African works, its availability in English has been central to its ability to transcend geographical lines – offering a wealth of Yoruba metaphor and context in an English language-text. However, this adaptation retains the original Yoruba language of the community. Only the English denizens, and their clan, speak English in brief stretches. With this decision, Bandale’s film became the first Yoruba film to premiere at TIFF, which in itself is significant for a festival that’s been run for 46-years. And language has been a concern for many clashes of culture featured at TIFF this year.

In “The King’s Horseman,” the Oyo people speak in Yoruba to the colonisers; neither side has a translator to interrupt the drama. It’s an intriguing choice, either suggesting bilingualism or a shrewd case of movie-magic. The characters merely understand each other, even as their words speak of the linguistic rift between the subjects. This kind of rupture in language on film has been present for several films, such as the completely in English “The Woman King,” where characters argue about which language is supreme although the Yoruba language is not as centre as it is in “Horseman.” Elsewhere, in something like the biopic “Chevalier,” set in France, the narrative is primarily in English although it is meant to be understood that the characters speak French. The Yoruba at work in “The King’s Horseman” feels significant and what’s more it’s with the linguistic dexterity that the music and rhythm of the film is best felt. To read a Soyinka play is not to really retain the fulsome way that cultural music complements it. To watch this adaptation is to enjoy the full rhythm of language in action.

As Elisin enjoys his wedding night even as the preparation for the rituals begin, Thomas Adetunji’s editing earns much from the quick intercutting between the sacredness and a society ball for the colonial elite across town. Although the weight of the colonial spirt hangs over the film, they are only briefly onscreen – foils to tradition more than anything else. “The King’s Horseman” does not condescend to explain to them, or to contemporary audiences, why a defence of the ritual suicide is necessary. And the fact that the film premiered amidst Elizabeth II’s own death, where peculiar British customs, also came into view, made a tense moment where Olunde (Elesin’s son) urges a white sceptic to allow that each tradition knows how best to preserve their own legacy all the more resonant.

And legacy means much here. “The King’s Horseman” is carrying the weight of Soyinka’s legacy on its back, but this is confident and engaging work. Bandele is an expert director of actors. The standout here is Shaffy Bello, as Iyaloja, the mother-figure of the community, who is giving a masterful performance that commands the screen. Her work is key to ensuring that the nuance is not lost here, and in her – she luckily gets the film’s last key moment – the film finds its strongest asset.

There’s still a note of something studied at work here, a familiar tone of respect for Soyinka’s words and a slight predilection for what feels like a desperate need to get to the ending where the story reveals what it’s about. Bandale might have benefitted from something a bit more languorous in his approach and one may wonder, for example, what a radical adaptation may look like. But, then, the deference to Soyinka is a sign of his legacy. Adetunji’s editing favours swiftness in a way that doesn’t always support the themes here, which require some pondering. One benefit of their swiftness is the way it exacerbates the temporal urgency, though. Events feel accelerated so that the film covers a single evening in a way that makes the hurtled trajectory from inciting action to tragic reality even more startling. In other moments, an actual arrest of a tribe member and the questions of what is happening who it is happening to and why it’s being allowed to happen, all feel slightly too rushed. But, as an artistic unit, “The King’s Horseman” feels confident in its assertions and itself. The ending is one moment that feels wonderfully sustained. Rather than leaving us where tragedy rips through it, we stay a while longer. As the community mournfully makes their walk back home, underscored by tribal singing, it feels like a thoughtful moment to turn our gaze to the community rather than a single figure – one of the story’s essential themes.

The film’s lack of languor becomes understandable because “The King’s Horseman” does not have the luxury of insouciance. When the new version of Jane Austen’s “Persuasion” came out this year, it was the first feature-film adaptation, but it had been adapted four-times for television already. For all the novelty of this being a feature film, Austen lovers could shrug and look forward to the next televisual “Persuasion”. And there will be a next and a next and a next. There’s no such blind certainty for Soyinka’s play or any other great play or novel from the African tradition. Even the relative success of “The Woman King”, and its celebration of the Oyo people in the 19th century is not really a signal of success for African stories but American iterations of them. It makes the premiere of “The King’s Horseman” feel burdened, adding a note of elegy that only deepened as the film premiered in the wake of Biyi Bandele’s untimely death at 54, a few weeks before this – his third film – had its world-premiere. What legacies are left to be passed down? Who is preserving them?

“The King’s Horseman” is preoccupied with the questions and the film retains the same ambiguity borne out of exhaustion that the original tale provokes us to think of. Its existence is credit enough but how lucky too that it bears that weight and manages to present its own singular approach. Shaffy Bello’s performance is the highlight, but the entire film is expertly performed, offering various ideas of the many stories contemporary and colonial Africa have so to offer.

The King’s Horseman will premiere for audiences on Netflix later this year.

This piece was filed as part of coverage of the 2022 Toronto Film Festival.