The recent revelation that the number of people in the English-speaking Caribbean estimated to be facing moderate to severe levels of food insecurity has risen by 46 per cent over the last six months, is certainly grim news. Periodically, we have had warning shots fired across our bows, particularly those which, in recent years, have pointed to the mounting regional indifference to strengthening its agricultural base. This has come alongside concerns voiced over the desirability of reducing extra-regional food imports.

Both of these concerns were ventilated earlier this year in the wake of a high-profile initiative to step up agriculture and agro-processing in the Caribbean as part of an overarching strategy, not just to increase regional food production, but also to create a structure to ensure efficient and effective food distribution across the region.

Amidst the noise about 25 by 2025 and the various other strategies articulated as part of a commitment to enhanced regional food production and distribution, we are now being told through a recently conducted study by Caricom and the World Food Programme (WFP) that with around 57% of the region’s people facing food insecurity we are confronted with something of an emergency.

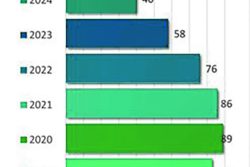

What stands out in the report is the revelation that there has been a significant increase in households that have fallen into moderate levels of food insecurity and that overall, the number of food-insecure people has increased by 1.3 million over the past six months. Deeply alarming, to say the least.

What has been a seeming continual decline in the region’s food security bona fides has been attributed in large measure to rising costs for food and other commodities, which is the same as saying that it is affordability rather than a substantive food shortage that is the main cause of the crisis. A section of the study reported that in the week leading up to the survey, almost 6% of people in the English-speaking Caribbean reported going an entire day without eating. This disclosure in itself is scarcely believable. Reportedly, a further 36 % of respondents skipped meals or ate less than usual, and 32 % ate less-preferred foods in the week leading up to the survey.

It gets worse. The recent survey, reportedly, was told of people whose circumstances had become sufficiently dire as to cause them to liquidate their assets and use the returns to meet basic material needs. This, it has to be said, is virtually unheard of in the region. Unsurprisingly, the WFP’s representative is on record as saying that the “negative coping strategies” that have been adopted to respond to the prevailing food security emergency “are unsustainable… and we fear that these short-term measures will lead to a further increase in the number of people who are unable to meet their daily food requirements.”

It is, of course, all well and good to assert that much of the problem resides in external factors which threaten livelihoods and the ability of people to meet their basic needs. What can hardly be denied is that, to a great extent, the food security profile of the region as reflected in the report, is largely self-inflicted, much of the problem reposing in the drastic reduction in food production.

Widely regarded as the breadbasket of the Caribbean, Guyana, over many months, has had to address alarming price hikes in fruit and vegetables. It has also been reduced to what most Guyanese would consider the indignity of having to import food items that include tomatoes and citrus,, which are sold on the local market at astronomical prices.

According to a senior Caricom official, what the report also says is that “for the first time in over two years, people’s inability to meet food and essential needs were top concerns, followed by unemployment.

“Caricom recognises that further support is necessary to reduce the level of need in the region and establish systems which facilitate access to nutritious food for all,” the official said. “Leaders in the region are actively engaging with decision-makers across all relevant sectors to identify solutions for increasing food production and reducing import dependency within the region in order to reduce the cost of food.”

That is just the kind of bureaucratic language that rubs Caribbean people the wrong way when there is no discernable evidence of these engagements between and among Caricom Heads of Government.

Just a few months ago, the food security status of the Caribbean had come under a region-wide microscope through widely publicised events in Guyana, Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago. There was an attendant commitment among some Caricom Heads to work together to help prepare a blueprint that would, hopefully, lay the foundation for the realisation of a 25% reduction in extra-regional imports by 2025.