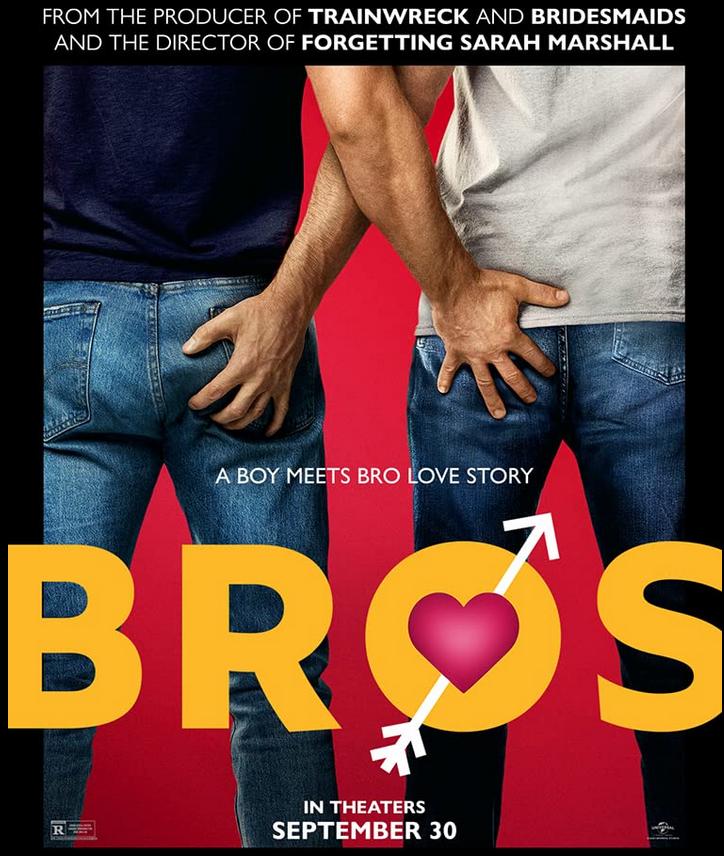

“Bros” is the first of its kind. Billy Eichner, the male lead and cowriter of the film’s script, has been telling everyone for months. The “first of its kind” plaudits are everywhere. From the film’s premiere at TIFF earlier in September, to the long press-tour for months in the run up to its theatrical release at the end of September. “Bros” is the first studio backed gay romantic comedy to be released in theatres. It is also, significantly, full of gay actors playing gay characters – a decisive rejection of the gay-for-pay mode of so many gay films in and out of Hollywood. Is it a win for representation? Undoubtedly. Is it a win for cinema? Not so much.

“Bros”, in theory, is about the relationship between its main couple, Bobby and Aaron. Bobby, played by Eichner, is the host of a podcast on gay culture and LGBTQ history, loud and opinionated and dismissive of the muscley gay culture that runs the city world. Aaron, played by Luke Macfarlane) is an office drone by day and a gay lothario by night. Both are emotionally unavailable, they confess, unready for a relationship. For Bobby this unavailability manifests in a judgemental distancing himself from the sexualised gay culture and a constant exasperation with the superficiality around him. For Aaron, and his constantly bare chest, his emotional unavailability manifests in casual sex with a string of men happy to ogle his sculpted body. When we first meet him, he’s preparing for a threesome with a happy couple. This set-up provides some potentially interesting conflict. Aaron seems nonplussed and vaguely charmed by Bobby’s opinionated demeanour. Bobby is clearly attracted to Aaron’s body if not his mind. Opposites attract, right? Perhaps. But that kind of romantic overture would depend on a film willing to really needle at both its leads. “Bros” is not that film. Not really.

Despite its overt appearance of being a romantic comedy, “Bros” is too hewn to the perspective of Bobby to feel equally yoked as a romance. Eichner’s celebrity persona is prone to vaguely comedic lectures about things. “Bros” puts that essence into practice. Bobby spends much of the film offering lectures – about the state of gay culture, about the watered-down nature of gay media, about the dynamics of queer intersectionality, and then finally about the way to create a good romance. There is a constant state of indignation that looms over the film. In one amusing motif, we see escalating versions of Hallmark movies centred on states of queerness – a polyamorous romance, a bisexual romance, etc. It’s hard to separate the film’s own indignation from Bobby, who spends the entire film sermonising on one thing or the other. And so much of the indignation feels bitter. If complaining is an art, Bobby is a savant. It’s a realistic character trait, but “Bros” struggles to distil that specific trait in a way that coheres to the film, rather than interrupts it. Even when viewed as a lecture, its ethos is muddled when Bobby feels blinkered in his vision of what should be acceptable for queer culture, while engaging in his own mixed messaging. The weight of trying to engage with too much, leaves “Bros” feeling overstuffed and indistinct rather than genuinely realised.

As an artistic work, “Bros” feels as if it is on the defence for much of its running time – bristling with a self-awareness that finds it meta-textually commenting on itself and announcing its own value, with condescension for its peers. If it had an internal monologue, it might sound like, “This gay culture is commercialised and hollow, but this is my gay culture and I know what’s best.” I can be generous and recognise the weight of “first” that Eichner and the rest of the film feel, but “Bros” feels neutered by the necessity of that weight rather than engaged in creating a story that exists beyond those expectations. Any piece of media from a disenfranchised group will have some level of scrutiny, and the large-scale nature of “Bros” amplifies that. But the fact that “Bros” only sees itself existing within that myopic scrutiny interrupts the kind of charming nuance that a film in this genre may benefit from. Although the film is directed, and cowritten, by Nicholas Stoller, Eichner’s spirit feels like the greater authorial voice. “Bros” is less a comedy, even less of a romance, and more of a lecture – however good-naturedly it thinks it may be.

Bobby and Aaron bond over the state of gay media, where straight actors perform gayness for audiences or where tidy versions of queerness become palatable to the hetero-patriarchy. These are genuine concerns for queer creators and audiences. But “Bros” struggles to thread its inclination for cultural screed to one that fits into the shape of a film that sees beyond its own sensitivity. And it becomes muddled when the film itself feels caught between its critiques and its desires. The first studio-backed gay romantic comedy, yes. But that first belies the ways that “Bros” isn’t really risky. And this would be less of an annoyance if “Bros” wasn’t convinced of its own radicalism. But it’s more than the language of Billy Eichner’s own inward-looking that feels baked into “Bros” certainty of its own radicalism. It argues for a rejection of safe and easy, and the fact that it features queer images and in-jokes, characters who are trans, bisexual and lesbians, is important. But there is a potent disingenuousness in the film’s approach to itself that feels complicated when it resists its own complicity in the palatable. Bobby is dismissive of the body obsession in gay culture but is obviously aroused by Aaron’s body. The film refuses to confront or to examine the complexities of the push and pull between desire and disgust that could make for something more thoughtful.

There is a sex scene in “Bros” that comes about a third into the film that I’ve been grappling with since I saw it. It’s the first sustained moment of sex between the two men alone. It is not erotic and the lack of eros bothered me. Yes, “Bros” is a comedy; the almost kneejerk undercutting of this moment of intimacy might be read as the film’s own willingness to laugh at itself – but in this film about this subject is that approach actually transgressive? As the audience around me roared with laughter as the sexual antics between Bobby and Aaron grew increasingly ridiculous, it felt like a way to make things more palatable. It’s easy to laugh at gay intimacy. In the hetero-patriarchal world of Hollywood media, the gay characters on the side have been used for comedy relief. When Aaron and Bobby embrace, in a vaguely kink adjacent encounter, and the camera draws back to position the act as one that is distinctly unsexy but very hilarious, I winced. Even the funniest romantic comedies find moments for the tender, and it feels telling that “Bros” never seems confident enough to be tender about sex, or to even convince us that this relationship can exist beyond the monogamous culture of straightness.

What’s more, the moments where the film allows Bobby to be critiqued feel scripted to allow him a level of autonomy that feels imbalanced in the relationship. Bobby is the authorial voice here, and the film suffers by never interrogation the worst of his impulses. In “Bringing Up Baby,” when Katharine Hepburn’s thoroughly exhausting (but wonderful) Susan Vance wears David Huxley down into something resembling love, the film is happy to laugh at her. Her strident exhausting nature is as much fodder for critique and laughter as is David’s own reservedness. “Bros” does not feel as equally yoked, its viewpoint is too shorn to Bobby and with that the lightness (and litheness) of touch to really be charmed by this dissipates.

What makes a good romantic comedy? There’s no one formula, but if there were one, I’d be convinced that contemporary Hollywood has lost it. Romantic comedies of this century often lack the nuance, the charm, the charisma that was so essential. The rare great American romantic comedies, like “Brown Sugar” and “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind”, feel like outliers. There’s a small smattering of other options, but mostly today romantic comedies lead you to a couple and announce that we must love them together without ever really articulating why this relationship matters. And so, for all the newness of its identity politics – finally, gays get to be tiresome and tedious in their own romance! Progress! “Bros” feel very much like more of the same. It would be less arduous if “Bros” wasn’t so self-reflexively and self-defensively caught up in the image of its own alleged audacity. Representation is valuable, but it can only take us so far.

In an ideal world, I’d love to be a lot more thoughtful about assessing “Bros” than engaging in just an ideological critique of it but “Bros” as a piece of cinema (allegedly) is more concerned with its ideology than its own aesthetic astuteness. And to be fair to it, this has been par the course for romantic comedies for too long. Earlier this year, the equally unfunny and unromantic “The Lost City of Z” was a reminder of this, and it’s incredibly exasperating. It’s a larger problem when major studio comedies seem unable or unwilling to engage with cinema as a form of visually communicative medium. But it congeals further in an awareness of comedy only as linguistic (or allegedly) with no real sense of the spatial. “Bros” is most confident in its comedy when it features a bit where Eichner speaks very loudly or engages in some kind of wordplay, “Bros” communicates primarily through word, rarely through images. And how could it not?

“Bros” is a sermon. And it is one I am amenable to, as a sermon. It’s hard for many gay men – even cisgendered white gay men who are the leads – to not feel the chip on the shoulder that is homophobia. This script is teeming with ideas that emerge from that awareness. But being lectured to for two hours, even when it attempts to hide itself in jokes, isn’t elegant and isn’t romantic and it’s not quite comedic. The film itself cannot step back far enough from Bobby’s perspective to interrogate those feelings of exhaustion he wears. It’s hard for such a character to stir feelings of fidelity, romance or even passion. In a word, he is exhausting. Even exhausting people deserve to be loved, though. Some of the best romantic heroes (and heroines) of Hollywood’s heyday were exhausting. Then the films would grapple with them, give them a character foil by way of romantic partner ready to spar with them. But in “Bros” that dynamic is absent. Eichner shouts, McFarlane acquiesces. It is not the stuff that movie magic is made of. But it is also not the stuff that “realism” is made of.

“Bros” is the first of its kind, and there are likely to be many pieces announcing all the queer first that it scales so well. But even in its dogged devotion to being first, that its memory of queer films is relegated to constant jokes about “Brokeback Mountain” and “The Power of the Dog” feels equally myopic. There is so much more to queer history than low hanging fruit of Oscar winning films about queer by straight filmmakers and actors. But the chip on its shoulder becomes the shape of its entire approach to itself, and so the romantic comedy is only a sleight-of-hand for sermon. The words are there, and the feelings are valid. But where’s the romance? Where’s the humour? Where’s the tenderness? While “Bros” luxuriates in being the first of its kind, maybe the second-of-its-kind that comes after will be better.

This piece was filed as part of coverage of the 2022 Toronto Film Festival.