OSLO, (Reuters) – Jailed Belarusian activist Ales Byalyatski, Russian rights group Memorial and Ukraine’s Center for Civil Liberties won the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize yesterday, amid a war in their region that is the worst conflict in Europe since World War Two.

The award, the first peace prize since Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine, has echoes of the Cold War era, when prominent Soviet dissidents such as Andrei Sakharov and Alexander Solzhenitsyn won Nobels for peace or literature.

The prize will be seen by many as a condemnation of Russian President Vladimir Putin, who was celebrating his 70th birthday on Friday, and Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko, making it one of the most politically contentious in decades.

“We believe that it is a war that is a result of an authoritarian regime, aggressively committing an act of aggression,” Norwegian Nobel Committee chair Berit Reiss-Andersen told Reuters after the announcement.

She said the committee wanted to honour “three outstanding champions of human rights, democracy and peaceful co-existence”.

“It is not one person, one organisation, one quick fix,” she said in an interview. “It is the united efforts of what we call civil society that can stand up against authoritarian states and, or, human rights abuses.”

She called on Belarus to release Byalyatski from prison and said the prize was not aimed against Putin.

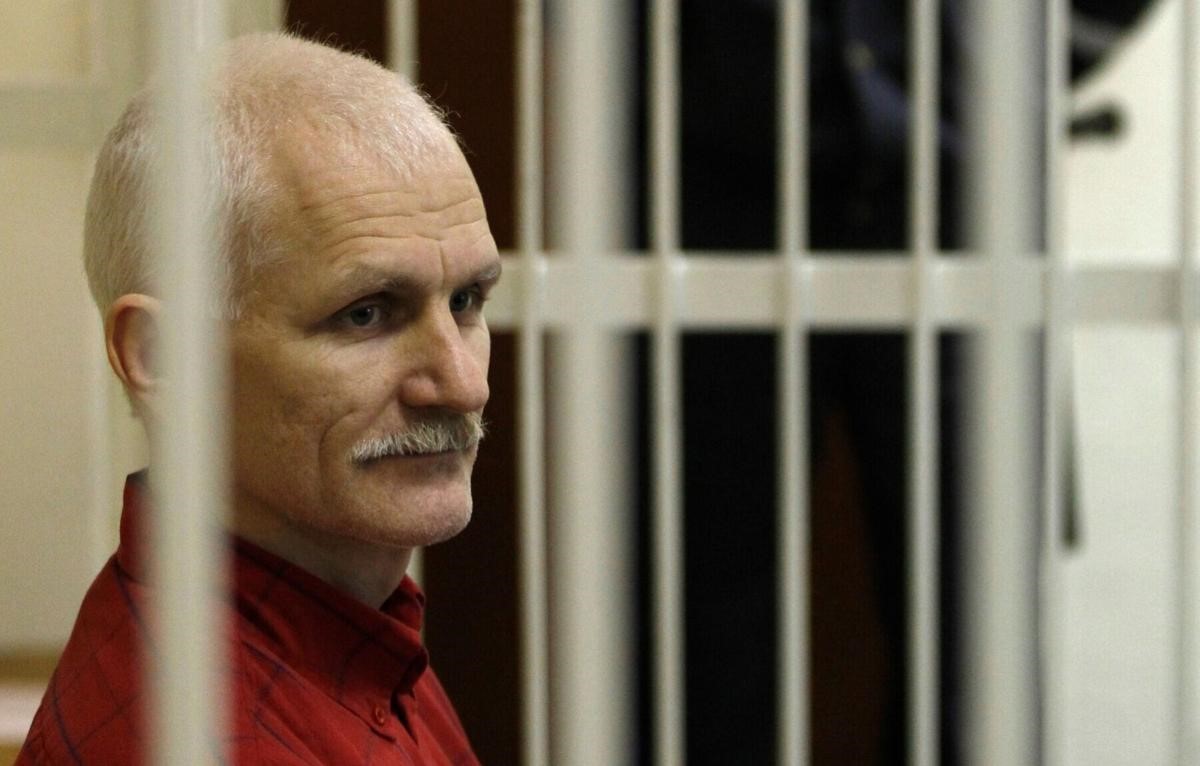

Belarusian security police in July last year detained Byalyatski, 60, and others in a new crackdown on opponents of Lukashenko.

Authorities had moved to shut down non-state media outlets and human right groups after mass protests the previous August against a presidential election that the opposition said was rigged.

“The (Nobel) Committee is sending a message that political freedoms, human rights and active civil society are part of peace,” Dan Smith, head of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, told Reuters.

He said the prize would boost morale for Byalyatski and strengthen the hand of the Center for Civil Liberties, an independent Ukrainian human rights organisation, which is also focused on fighting corruption.

“Although Memorial has been closed in Russia, it lives on as an idea that it’s right to criticize power and that facts and history matter,” Smith added.

Byalyatski’s wife told Reuters he may not even know of the news, which she tried to break to him in a telegram to a Belarusian prison.

In Geneva, the Russian ambassador to the United Nations said Moscow was not concerned about the award. “We don’t care about this,” Gennady Gatilov told Reuters.

In Belarus, the award was not reported by state media.

Founded in 1989 to help the victims of political repression during the Soviet Union and their relatives, Memorial campaigns for democracy and civil rights in Russia and former Soviet republics. Its co-founder and first leader was Sakharov, the 1975 Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

Memorial, Russia’s best-known human rights group, was ordered to be dissolved last December for breaking a law requiring certain civil society groups to register as foreign agents, capping a year of crackdowns on Kremlin critics the likes of which had not been seen since Soviet days.

Memorial board member Oleg Orlov called the prize a “moral support”, but when asked by reporters if it would help to protect his organisation or its work, he said “I fear not.”

Speaking after a Moscow court hearing to decide whether Memorial’s archives should be handed over to the state, Orlov said: “When one country crushes human rights, that country becomes a threat to the world.”

“We are continuing our work defending human rights,” he added. “It hasn’t stopped, it goes on.”

The award to Memorial is the second in a row to a Russian person or organisation, after the prize last year went to journalist Dmitry Muratov and to Maria Ressa of the Philippines.

The executive director of Ukraine’s Center for Civil Liberties, Oleksandra Romantsova, said winning the award was incredible.

“It is great, thank you,” she told the secretary of the award committee, Olav Njoelstad, during a phone call that was filmed and broadcast on Norwegian television.

The group also wrote on Twitter of how proud it was.

The award to Byalyatski could help draw attention to some 1,350 political prisoners in Belarus, exiled opposition politician Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya told Reuters.

“I am really proud to see Ales Byalyatski as the winner,” she said. “(He) has through all his life protected human rights in our country.

“He is a prisoner for the second time, this is showing how the regime is constantly persecuting those who fight for human rights in Belarus.”

When Lukashenko’s security forces cracked down after the 2020 election, Byalyatski, founder of the civil rights group Viasna, chose to stay in the country despite the high risk of arrest.

He was eventually arrested in July last year and accused of tax avoidance, to which authorities recently added a new charge of making illegal money transfers.

He is in prison awaiting trial, and faces a sentence of up to 12 years if convicted. He was previously imprisoned from 2011 to 2014.

“We don’t know what Ales is feeling now,” said Pavel Sapelko, a laywer at Viasna now living in Vilnius.

“It’s an earned reward, a recognition of the many years of his fight, and a recognition of Viasna, his main brainchild,” said Sapelko.

Byalyatski is the fourth person to win the Nobel Peace Prize while in detention, after Germany’s Carl von Ossietzky in 1935, China’s Liu Xiaobo in 2010 and Myanmar’s Aung San Suu Kyi, who was under house arrest, in 1991.

The prize will be presented in Oslo on Dec. 10.