Olivia Wilde’s new film, a “psychological thriller” about a woman in an idyllic 1950s suburb who begins to realise that something is very wrong is a far cry from her directorial debut, the teen comedy “Booksmart”, but the two have more in common than you would think. In “Booksmart” (2019), a high-school comedy about two very earnest and very liberal teen girls, Wilde’s approach to creating the world felt mired in an online awareness that made the scenarios in the film ring incredibly hollow. It was more than the generation gap that comes with adults writing for and about teenagers. So much about “Booksmart,” from its dialogue to the way the camera engages with its utopian world of high-school drama to the ostensibly (but not really) casual dynamics of its high-school cast, feels premeditated; a kind of rehearsed joke constructed from a laundry-list of important topics that would capture the zeitgeist, rather than a real messy slice of teen life. The characters were suitably engaged with the right politics, and the right hot-button talking points but the actual substantive complexity behind the ideas overlook any actual difficult complexities of things like race, or class. The same can be said about her new film.

Olivia Wilde’s new film, a “psychological thriller” about a woman in an idyllic 1950s suburb who begins to realise that something is very wrong is a far cry from her directorial debut, the teen comedy “Booksmart”, but the two have more in common than you would think. In “Booksmart” (2019), a high-school comedy about two very earnest and very liberal teen girls, Wilde’s approach to creating the world felt mired in an online awareness that made the scenarios in the film ring incredibly hollow. It was more than the generation gap that comes with adults writing for and about teenagers. So much about “Booksmart,” from its dialogue to the way the camera engages with its utopian world of high-school drama to the ostensibly (but not really) casual dynamics of its high-school cast, feels premeditated; a kind of rehearsed joke constructed from a laundry-list of important topics that would capture the zeitgeist, rather than a real messy slice of teen life. The characters were suitably engaged with the right politics, and the right hot-button talking points but the actual substantive complexity behind the ideas overlook any actual difficult complexities of things like race, or class. The same can be said about her new film.

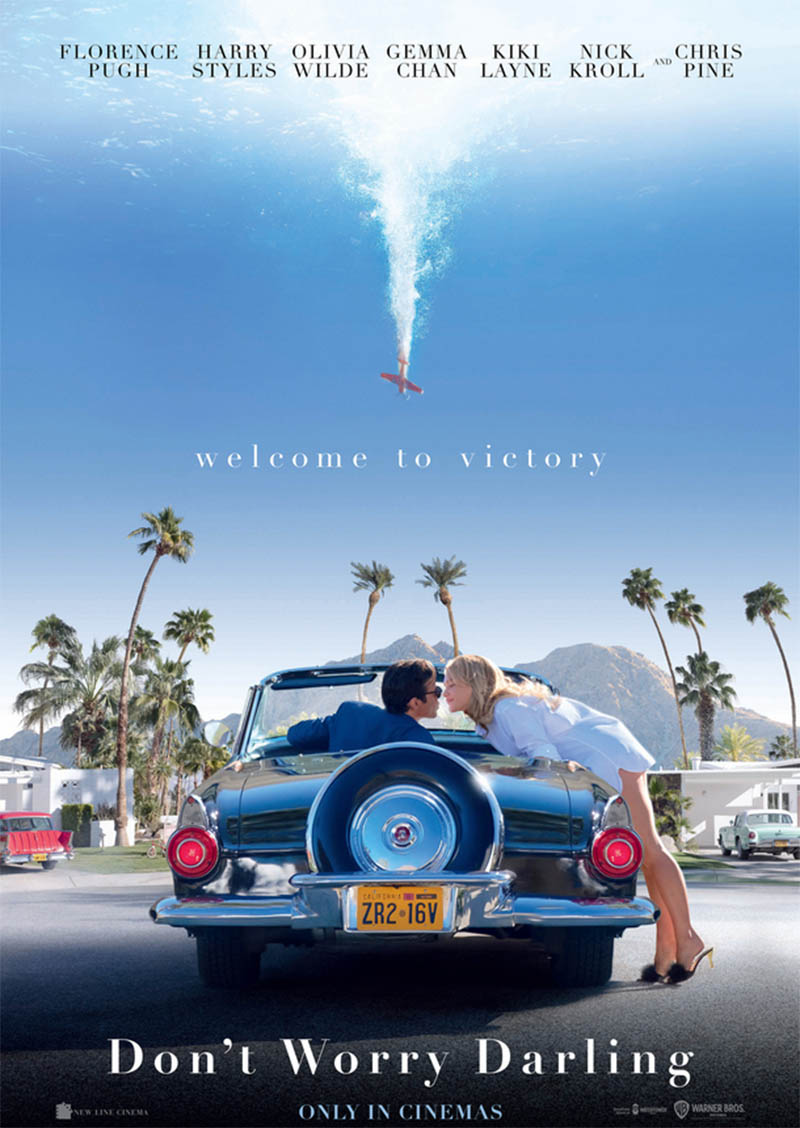

Our window into “Don’t Worry Darling” is Alice (Florence Pugh), a young housewife enamoured with her husband Jack (Harry Styles, following up his dull performance in “My Policeman” at TIFF with another dull performance in the name of consistency). The two live in a company town, Victory, California, where all the men work beyond the desert. We meet the couple at a neighbourhood party with other couples – a picture of 1950s domestic bliss. Jack and Alice are the youngest couple, and the prettiest. They are caught up in the throes of young passionate love. A friend jokingly mocks the sounds of marital bliss coming from their house every night. Alice stays home, makes breakfast and dinner, cleans the house enthusiastically, attends ballet class with the women in the neighbourhood and awaits Jack every night. The sameness and symmetry alert us early on that something is amiss. The wives all walk their husbands to the car at the same time, in varying states of dress or undress. The men all drive the same kinds of car. They are all equally vague about what their jobs are.

The film telegraphs that something is off across every frame from the get-go, so much so that it is not a question of if something is wrong but how and why. The revelations, when they come, are not especially shocking but they reveal an awareness of pop-culture that the film seems to hold as a shorthand for an actual exploration of themes. In the lead up to the film, Wilde has spoken about the Jordan Peterson inspired character played by Chris Pine, an obvious sign of the way the film exists with the kind of self-awareness that is incredibly keyed into its own referents. “Don’t Worry Darling” is very self-aware, with an unsubtle invocation of incel culture, toxic masculinity, and patriarchy. It is filled with talking points – questions about women’s complicity in the patriarchy, questions about what femininity looks like and the rupture between old and new ideas of domestication. What is absent in “Don’t Worry Darling” is anything that feels like a completely thought-out film, beyond the semblance of ideas it nods to.

We’ve seen this type of fable before. A world of ostensible perfection where something troubling lingers beneath. Cracks begin to show. Margaret (a wasted Kiki Layne, who tries her best), a housewife, seems to be losing her mind and rather than invoking sympathy from her fellow women is treated as a pariah. Alice and Jack carelessly have passionate sex in the bedroom of Frank, the leader of the town, as Frank watches on. Alice sees a plane crash while on a bus ride and after going to investigate begins to have morbid hallucinations that threaten the equilibrium and balance here. Soon Alice finds herself uncertain of her surroundings and her life and “Don’t Worry Darling” launches into its treatise on the ills of society. It’s clear that there is an idea here, however trite. A period film that excavates contemporary responses to male resentment. These ideas are stitched together, and in the gaps where each stitch loops into the other are a vacuum which “Don’t Worry Darling” forgets to fill with the muscle and sinew of what should be a movie.

Midway through the film, Alice mournfully regrets not taking Margaret’s concerns more seriously. “I was her friend,” she insists to a hapless Jack. The moment doesn’t register beyond the shape of the lines and frustrates with the superficiality the film expects us to gloss over. The film hasn’t given us anything to suggest anything resembling that. Margaret is not the only Black character we see, but she is the only one with substantial lines. Her presence promises a surprisingly diverse 1950s America, but whether before or after the film’s last act reveal, Wilde’s approach to considering race in America feels facile. Victory’s potentially diverse population feels too indistinct in what seems to be a White American space. Beyond Margaret, Frank’s wife is played by British-Chinese actress Gemma Chan, and another husband, Peter, is played by Indian actor Asif Ali. It feels strange that the film, which performs some version of social critique in its final act, seems ignorant of the racial dynamics – especially when Margaret’s pain and trauma become the catalyst for Alice’s self-actualisation. When Alice, and her cadre of other housewife friends – all White – turn their backs on Margaret, I’m not sure whether we’re meant to read the racial dynamics into this. But, like many things in “Don’t Worry Darling” we are left to infer the conclusion as well as the inciting query.

In another scene, Jack insists that things in the neighbourhood used to be so wonderful before the doubts crept in. Wilde is so engrossed in the directorial thrills of presenting Victory as unnerving, the film provides us no context to suggest that this idyllic world ever seemed enchanting. Pugh’s interpretation of Alice feels incongruous with the things the film compels her to do, she is too knowing and sentient to play the wide-eyed woman who slowly learns over time that her surroundings are rotten beneath the surface. And as directed by Wilde, this world is too obviously malevolent for us to be convinced of the characters’ own ignorance. There is not a single moment in “Don’t Worry Darling” where its veneer does not seem bathed in falsity. And this could be all well and good if the film engaged with its own falsity, but the climax where things are finally “revealed” depends on some investment that what has been built up is realistically formed. And just as the town of Victory feels hollow, “Don’t Worry Darling” feels similarly vacuous. Around the 90-minute mark, when the film begins to really go off the rails, it’s hard even for Pugh’s tenacity to make sense of the film’s own careless ambivalence. And by that point, what should feel taut, or earnest, or unsettling ends up feeling mostly very silly.

Like many things in “Don’t Worry Darling,” the film’s own emptiness feels like a self-reflexive way for it to avoid its own clarity of images; there is a constant obfuscation of intent that feels more like the film’s prevarication as praxis rather than a genuine awareness of what it wishes to articulate. Character relationships are feigned but never feel fully realised. We know a twist is coming because the film overplays its hand, and when it comes – equally muddled in presentation and intent — it feels like a broadly painted “answer” that lacks genuine complexity, but through its vagueness feels like a way to explain any previous complexity away. But it’s not so much that “Don’t Worry Darling” may be accused of having plot-holes, which is an unhelpful phrase anyhow. It’s more that “Don’t Worry Darling” doesn’t care to set the stage for any kind of nuanced relationship between these characters, any true identity to their surroundings and emotions, before they begin to self-destruct. Wilde, and her team, seem beguiled by the aesthetics of the 1950s but not with any investment as to what this place and time really means for these characters. The fact that company-towns fell out of favour in the 1930s under Roosevelt’s New Deal makes the very concept either deliberately inane or accidentally so.

It’s one thing for a movie to leave the audience to answer questions, but “Don’t Worry Darling” also leaves the audience to decide what questions are relevant, in what sequence they should be asked and then feign some idea of a response to them. It strategically teases ambiguity as a personality, while being truly bereft of any real argument about any of the themes it nods to. It feels like a movie made by and for the terminally online where merely motioning to a hot topic is confused with incisive engagement with it.

But the ambiguity which layers Wilde’s approach, Matthew Libatique’s glossy images, and Katie Byron’s oppressively tidy production design feels empty of any real point of view. What exactly is the perspective on any of this? There’s a level of care in the costumes of Arianne Phillips that feel thought-out and intentional in ways that feels very illuminating. They tell us more than the performances — and the script — as to what versions of these characters we are meant to respond to but although the costumes may sell the period illusion, “Don’t Worry Darling” itself can’t quite articulate the relationship between its concept and itself as a piece of film. Like “Booksmart”, its concepts and cultural awareness of the world we live in today feels more realised than any idea of how that works as a movie.

Wilde’s direction feels interesting enough in brief stretches, such as the sight of a sweaty Pugh walking through a desert in sweltering heat, or the revolving camera intersecting between husbands and wives, or a trippy dance sequence that emphasises the circle as a figure of despair. But the initial charm of the visuals doesn’t go anywhere and Wilde’s approach to it feels insubstantial, all superficial flourishes with little underneath that feels genuinely interrogative or revealing or thoughtful. This means that specific images or sequences thrill at first and then begin to feel pointless. An obsession with circles is initially striking but goes nowhere and becomes repetitive, while repeated sequences of coffee pouring establish a routine but to what end? Like every potentially engaging visually cue, the film seems fascinated by itself but without any sense of building momentum towards something tangible for the audience to engage with. And try as she might, Pugh’s performance – though committed – feels out place. There’s no way for her character to go, and so her committed performance feels lost in a film that can’t see out of its own limited perspective. There’s nothing to worry about here, because “Don’t Worry Darling” is empty of anything to really invest in. Great gowns, though. Beautiful gowns.