(Reuters) – As Haiti’s gang-induced humanitarian crisis deepened in October, a group of looters ransacked a supermarket in a well-to-do suburb of the capital Port-au-Prince, leading police to arrest over a dozen people and take them to a nearby police station.

They were not there for long.

Within hours, the station in the area known as Thomassin came under a hail of bullets from gang members led by a man named Carlo Petithomme, whose brother had been among those arrested, according to two security sources.

Petithomme goes by the alias Ti Makak, and leads a gang of the same name. They overpowered officers and released the looters as well as others who had previously been arrested, the sources said.

Reuters was unable to contact Petithomme for security reasons.

The brazen Oct. 10 assault, which is reported in detail for the first time here, shocked residents of an area that had been largely shielded from Haitian gangs, a group of which have created a humanitarian crisis by blocking fuel distribution.

While Ti Makak is not directly linked to the fuel blockade, its rise is a sign of how Haitian gangs can quickly evolve from a ragtag band of thieves into powerful warlords who can subvert the rule of law even in the country’s stablest regions.

It is further evidence of how gangs have expanded their power since the shocking 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moise, and the difficulties facing Prime Minister Ariel Henry in restoring order to the country.

Most gangs first emerged in the slums near the capital, but residents and merchants left those areas in response, said James Boyard, a security expert and professor of international relations at the State University of Haiti.

“With the aim of having access to new sources of income, the gangs now seek to settle in what were once ‘green zones,’ to carry out kidnapping and extortion,” Boyard said.

Haiti is now held hostage by a gang coalition called G9 led by Jimmy “Barbecue” Cherizier, a former police officer who in September began a blockade of the Varreux fuel terminal, a move Cherizier called a protest over a plan to cut fuel subsidies.

Many Haitians, as well as a growing number of U.S. policy-makers, believe that wealthy Haitians finance the gangs to further their own economic interests.

The blockade has left Haiti without fuel, triggering shortages of food and clean water, just as the country is facing a cholera outbreak. The United Nations has discussed a possible strike force to clear the blockade and resume fuel distribution, though it remains unclear who would lead it.

The last major foreign military force in Haiti, a 13-year U.N. mission known as MINUSTAH, was deeply unpopular by the time it ended in 2017 due to credible evidence that its troops caused a 2010 cholera epidemic as well as accusations of sexual abuse of underaged girls.

Gangs are also deeply enmeshed in the civilian population, meaning a standard military assault against them would carry risks of significant civilian casualties.

Haiti’s National Police did not respond to requests for comment on the police commissary incident or about Ti Makak in general.

Ti Makak now has a strong grip on Laboule, an area of steep, verdant hillsides to the south of Port-au-Prince, according to residents and security experts.

Since the 1990s, Laboule has been populated by well-off families drawn by the fresh air and sweeping views, some of whom built mansions and luxury homes. Laboule’s sub-districts are demarcated by numbers, and Laboule 12 has suffered a significant rise in gang activity. Its streets, which for years teemed with drivers, vendors, and restaurant-goers, are increasingly empty.

In 2021, when gangs took control of the main road heading from Port-au-Prince to Haiti’s southern peninsula, drivers began taking Laboule as an alternate route.

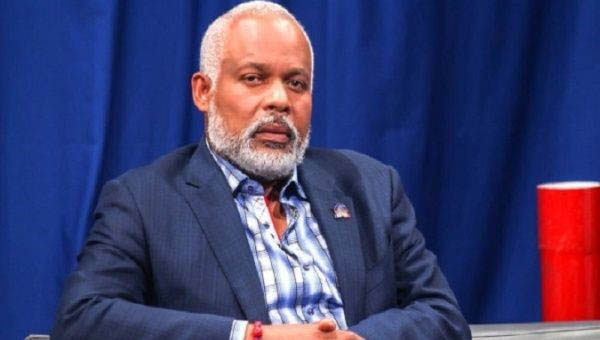

Well-known politician Eric Jean Baptiste was killed on Friday night in an apparent gang attack as he was returning to his home in Laboule 12, according to local media reports and a tweet by Prime Minister Ariel Henry on Saturday.

Ti Makak’s early activities are difficult to ascertain.

The group began getting attention when a police officer was killed in an anti-gang operation in January in Laboule 12. Local media reported that Ti Makak was responsible.

Around the middle of the year, a local entrepreneur started getting calls from unidentified men who demanded he hand over some of his shop’s merchandise at the request of a man described with grandiloquent titles such as “the commander.”

The entrepreneur, who for security reasons asked that neither he nor the specific nature of his business be identified, initially thought the calls were coming from neighborhood toughs pretending to have links to crime groups.

But the calls continued, he said, and a group later arrived in person, saying they were linked to Ti Makak. They became agitated when their requests for merchandise and cash payments were rebuffed.

The business has now sharply curtailed its activities due to months of threats as well as the overall situation of the country, said the entrepreneur.

“There’s nothing that can stop them, except for God or the angels changing their mind,” he said. “If they’re coming, they’re coming. In Haiti, threats are not empty.”

LAND CONFLICTS

Petithomme has remained relatively discreet in comparison with other gang leaders such as Cherizier, who enjoys appearing in public in tailored suits and has even invited foreign correspondents to press conferences.

In an interview broadcast by a little-known YouTube channel called RL Media Pro, a man wearing a cowboy hat and a bandana over his face who identified himself as Ti Makak was asked about the attack on the Thomassin police station.

He did not respond to direct questions about the assault, instead describing the events of that day as an effort to protect peaceful protestors from attacks by police.

“I won’t lie to you, if I wasn’t quick (to protect) my guys, the majority of my guys would have been victims,” said the man, without elaborating.

Petithomme has in the past said his family is from Laboule 12 and that farmers’ lands had been taken over by a man named Jean Mossanto Petit, a Haitian entrepreneur who for decades ran a successful lottery business and owns land in the area.

Reuters was unable to obtain comment from Petit.

Disputes over land titles, a chronic problem dating back to Haiti’s 1804 independence, erupted in bloody clashes near Laboule 12 around two years ago, according to Fenel Pelissier, a journalist who in October published research on the dispute for Haitian online media portal Ayibopost.

“(Petithomme) didn’t live in the area, but he returned when he heard that people living there had sold land to (Petit),” said Pelissier, who spoke with residents in the area but said it was unclear if any land transactions had in fact taken place.

Pelissier said that one official told him that around 60 people have been killed and 100 houses burned down as a result of the conflict.

Ricardo Germain, an independent security consultant, said Ti Makak’s rhetorical support for the poor signals that the group seeks, like many Haitian gangs, to win over a population suffering from a severe crisis.

“We can easily conclude that the Ti Makak band seeks to win the hearts of the people, particularly of those people who have been involved in acts of looting during recent protests,” Germain said.