Balance is a necessity of art, as in life. Without it, we feel off-kilter.

Balance is a necessity of art, as in life. Without it, we feel off-kilter.

As we begin to consider the Principles of Art, let’s do so by first considering balance and then emphasis. Balance in art relates to how the colours, lines, textures, shapes/forms, and space are arranged within a composition to allow for visual weighting that feels equally distributed. This does not mean necessarily that there is an equal distribution of these elements just that they feel equally dispersed and stable.

In art, we can speak of symmetrical and asymmetrical balance. In the case of both, such balance is realised across a vertical or horizontal axis. The axis in a work of art is the line that runs through the center of the composition, is horizontal or vertical, and therefore, is not a diagonal line. Composition refers to the arrangement of the parts to make the whole. The word can be used interchangeably with terms to denote a work of art such as artwork, painting, or sculpture. The vertical or horizontal axis is easily recognised in paintings and other two-dimensional works, but can you see that the Shiva Nataraja is balanced in relation to the vertical axis?

A favourite representation of mine is the Shiva Nataraja (Shiva as Lord of the Dance). Indeed, there are many sculptural representations of Lord Shiva doing the dance of destruction and creation. Nonetheless, we know it is hard to keep our balance when standing on one leg. Lord Shiva appears to do so effortlessly. But not only does he stand on one leg, Lord Shiva stands with his head and torso frontal-facing with his hips pivoted to the right as he raises the left leg so his feet are high above the knee of the bent standing leg. A difficult pose. But Shiva is no mortal. As if this is not enough of a feat, Shiva maintains his balance despite three of his four hands forming mudras over the raised left leg. If you draw a line down the center of the composition the two halves are not the same across the vertical axis. Nonetheless, the image feels stable. How so?

Shiva Nataraja is asymmetrically balanced. Positioned within a halo of flames, Shiva’s visual balance is possible because of strategic points of contact between his extremities and the circle of the halo. These points reflect each other. A line parallel to the base can be drawn between the hands and another connects the head and standing foot. Therefore, on either side of the vertical axis which his body overlaps, Shiva is literally and visually anchored to the circle at these two opposing points. I simply cannot think of another image that embodies asymmetrical balance as beautifully or as meaningfully as Lord Shiva as he stands on a symbol of ignorance.

Symmetrical balance on the other hand is evident when across the vertical or horizontal axis the two halves of the whole are the same. Mirror image. Radial balance occurs at several points in a circular fashion. A sunflower is a good example of naturally occurring radial balance while a rose window, found in Christian architecture is an example of a man-made shape with radial balance

Another useful principle of art is emphasis. Emphasis occurs at the focal point and the focal point can be found at the point or area of greatest interest within the composition. It can also be found at or near the point or line around which the work is balanced. Sometimes, however, a work has more than one focal point – a primary and secondary focal point. Sometimes too, the work is a focal, meaning it lacks a focal point so that the eye moves around the composition and does not get drawn to any point or area where it may rest.

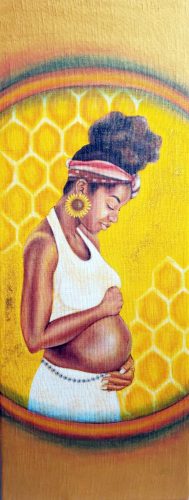

Alyce Cameron’s Oshun is a beautiful example of a work with multiple focal points. First, the curved lines at the top and bottom of the painting frame a maternal figure shown in profile. She demands that we pay attention to her. Her beautiful crown of natural hair, the scarf that adorns it, the large sunflower earrings, the serenity of the smile that caresses her lips and seems to be the source of the glow of her skin captivate our attention. Following the downward bend of her head, our eyes follow her arm to the hands that rest beneath the natural sag of her breast and under the protruding belly also requiring our attention. As the figure’s hands frame her maternal/pregnant belly, we realise here is the focal point – a mother cradling the unseen child within her womb.

Why do I suggest the main focal point is the obviously pregnant belly? In addition to the downward posture of the head that moves the eye to the belly along an invisible line, the belly is further made important by the arms which frame the belly and its condition of undress. Very significantly, this woman (presumably Oshun) is dressed with a scarf, earrings, and clothing but has raised the garment to allow the belly to be seen unencumbered by cloth.

Emphasis in a composition can be achieved by using the elements of art and the principles of design. In Cameron’s case, she has used lines, rhythm, and contrast to draw our eye to her principal area of interest.

Cameron’s painting Oshun is also very well-composed. The figure’s body overlaps the vertical axis without dissecting the body into two halves. However, while the main portion of the body is left of the vertical axis it is well placed so as not to create visual weight on the left edge of the composition. Likewise, the body is placed within the composition so the main focal point falls below the horizontal axis. Thus, the belly does not intersect with the literal (real) centre of the painting and this helps the painting to have a dynamism that would be lost if the two – the main focal point and the actual centre of the painting intersected. A fun exercise may be to imaginatively shift the figure around the canvas to see whether you agree with my analysis of Cameron’s composition.

It may enhance your formal appreciation of the Shiva Nataraja to assess it for a focal point. Is there a point of emphasis in the Shiva as Nataraja? Where is it, if it exists? While the Hindu God in the Shiva Nataraja subscribes to a centuries-old tradition, the Yoruba Orisha Oshun depicted by Cameron does not employ traditional forms. Instead, Cameron draws on symbolism associated with the Orisha, most notably the yellow colour, her embodiment of physical and inner beauty, and her association with honey.

In the next article, I will return to discussing an element of art.

Akima McPherson is a multi-media artist, art historian, and educator.