In 2019, two African MFA students—Yvette Ndlovu from Zimbabwe and Shingai Kakunda from Kenya—met while studying in the United States. Appalled by the lack of resources for and about Black speculative writers in their programmes, the two would frequently dream about creating the kind of space that actively facilitated, nurtured, and validated Black science fiction and fantasy writers. When the pandemic began in 2020, and programmes began to move online, the pair, along with H.D. Hunter and L.P. Kindred, would begin the Voodoonauts Summer Workshop (now Fellowship).

Together, the four have hosted three online workshops thus far, gathering writers, artists, poets, editors and publishers together. During these workshops, they have done craft classes, genre-specific writing sessions, lessons about African story-forms and speculative literary cannons, and tutorials for navigating the science fiction, fantasy and horror sides of the publishing industry.

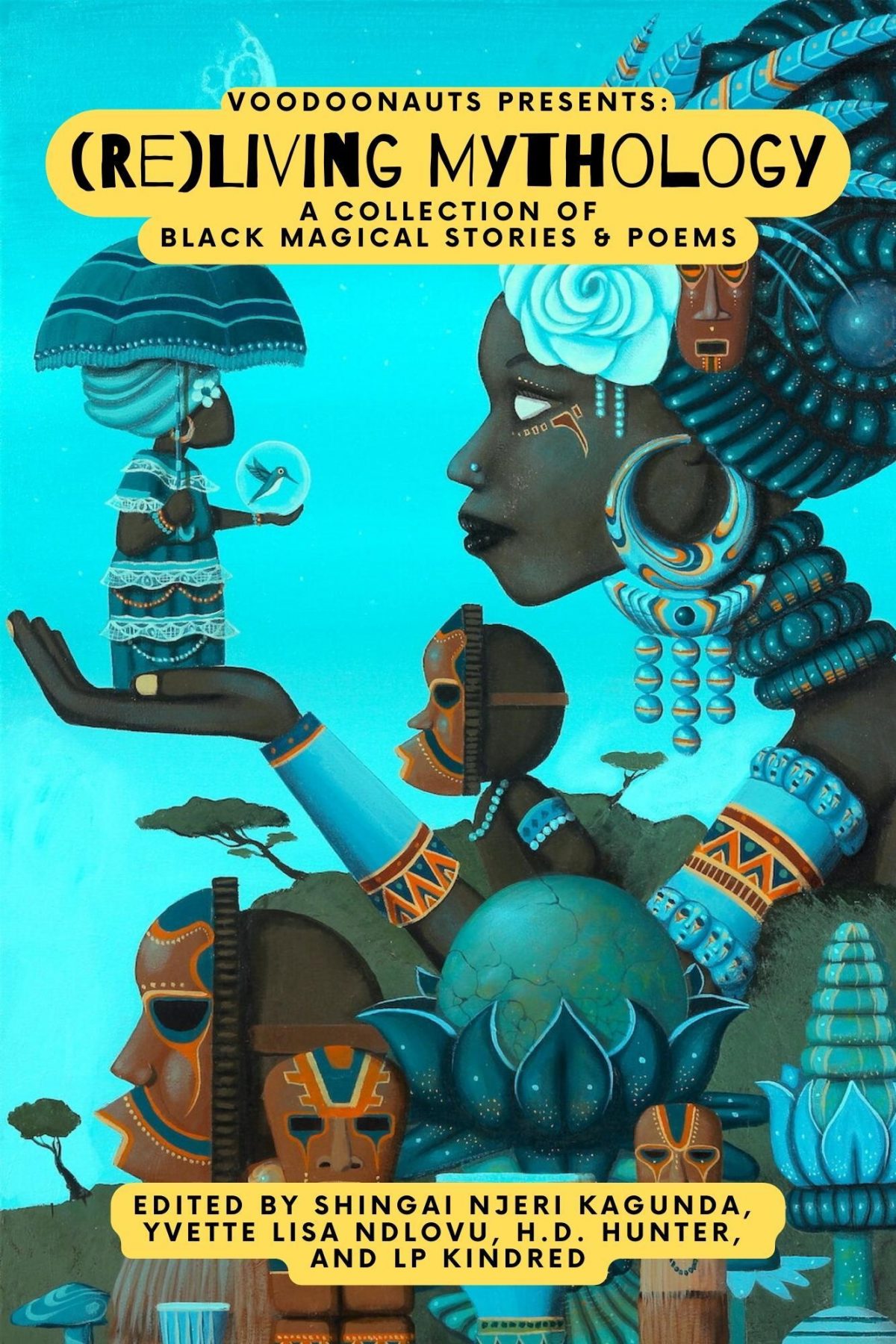

But most importantly the Voodoonauts team practice what they preach. Next week, they are publishing their first collection of student and facilitator short stories and poems through Android Press: Voodoonauts Presents: (Re)Living Mythology – A Collection of Black Magical Stories and Poems. This collection is a testament to the hard work and dedication the team puts into ensuring that their students can have work out in the world, and it serves as a display of their students’ talent. This book includes a mixture of fourteen short stories and poems, in which the writers tap into their histories, cultures and passions as they re-imagine aspects of mythologies in fresh, new and trippy ways

While I would love to review all of the entries, I have neither the space nor time, but here are three of my favourites from this delightful collection.

“The Names We Take” by S.O.F

“Born shortly after my grandfather’s death, I was designated his reincarnation and dubbed, Babátúndé. There was no money for new names, only incarnations or inherited ones. My grandfather had been called Àjàyí, and it seemed as if he had lived his entire life just as he was born, with his face down – oppressed and trampled on, seated in abject poverty and disgrace. And as his heir, I had walked the same bleak path. But no longer, I remind myself, not anymore.”

“The Names We Take” is one of the collection’s stories that explores parent-child relationships. It examines the sacrifices parents make so that their children can have long, fulfilling lives. For many parents this means ensuring that their children are clothed, fed, housed, and well educated. But what would you do if you could change your child’s destiny?

Enter Àjàyí, a poor Lagosian who only has a few hours left to change his newborn’s destiny before it is sealed at her naming ceremony. Names and naming are an important part of Yoruba culture, as a good name can shape your future. But good, new names are expensive, a luxury that can only be afforded by the rich. To ensure that his daughter can have a good name and that her sealed destiny is rich and fulfilling, he is determined to steal one.

He finds his target, the rich white General Manager of a local oil company and has gathered the materials and formulated his time down to the last dollar he needs for the bus ride home. He strikes. He steals! He hustles to the name dealer and distils his daughter’s new destiny and name down to its core. But that is the easy part. Now, he must get home and give his baby the new name and destiny before the sun sets. Unfortunately for him and his meticulous plan, Lagos itself seems determined to slow him down.

I loved the way this story explores parental anxiety, and the ways they go out of their way to ensure their children have better lives. Àjàyí battles poverty, class, and powerful exploitative systems to change the course of his daughter’s future. This story powerful statement about parental love, and the struggle for class elevation.

“The Visit” by Tina Jenkins Bell

“Senora moved from her couch toward the door, and true enough, it was Malcolm, towering over the four glass panes in her door. But the wretched thing Senora’s father called Walumbe was present, too.

“Walumbe hooked his chin over Malcolm’s shoulder and grimaced a nefarious smile. Senora grabbed her chest and gagged. He wasn’t done. He continued to toy with an oblivious Malcolm, palming Malcolm’s head with webbed bony fingers and his long nails rested like bangs on Malcolm’s forehead.”

“The Visit” also looks at parent-child dynamics, but this time looks at the relationship adult children have with their ageing and ailing parents.

Senora Glad Johnson is ill, having recently been diagnosed with a heart condition that causes her to have blood pressure spikes. These spikes, much to her son Malcolm’s horror—because Senora is determined to live alone—either cause severe chest pain or make her faint.

Malcolm wants Senora to sell her house and move in with him so that he can care for her, and his wife and children simultaneously. But Senora loves her independence and tight-knit community in Chicago and doesn’t want to be a burden on Malcolm. More importantly, she wants to keep him away from Walumbe, a wretched spirit that haunted her father, and who started targeting her since her illness began.

The pair butt heads during Malcolm’s visit, as he fusses over her health and living arrangement and she tries to hold onto her lifestyle and keep Walumbe at bay. Only when they start to talk to each other, and Senora explains their strange family history do they find a way to move forward together, and Senora gathers the strength she needs to banish Walumbe.

I spoke to Jenkins Bell about this story and what she had in mind while she was writing it. I was curious about the way she used Walumbe—a Ugandan folklore character from The Story of Kintu: the first man—in her story about an ailing woman in Chicago. She explained that Walumbe was always a meddlesome and nefarious spirit. In Kintu’s story, he is the embodiment of death and disease who came to earth uninvited and began stealing Kintu’s children away. He has a similar role in this story, as he tries to trick his victims into giving up their lives before their time.

Walumbe stands in for Senora’s fear, but also the trauma she experienced while caring for her ailing father and witnessing Walumbe’s terrible work. To defeat him, or at least keep him at bay, she needs to open up to her son about her history, trauma and current struggles. For Malcolm to help her in turn, he needs to come to terms with his mother’s needs and wants.

This requires them both to overcome their fears. Jenkins Bell noted that they are both afraid in this story, and when a parent or close relative is ill, their children or other family members are expected to step in and help. While this comes from a place of love, a fear-driven approached to caretaking often leads to a breakdown in communication: the caretaker tries to impose what they think is best for their relative without asking them about their wants and needs. This then leads to conflict, resistance and resentment.

But once the two are able to open up about their fears, concerns, wants and desires, they are able to have these tender moments that strengthens their relationship but also leads them to a better understanding of what they need from each other in the moment.

“Stars Born Blue” by L.P. Kindred

“Night came first

Her name was Nulyk

Her Black was beautiful.

Expansive, endless, eternal, the only

Nulyk remains perfect.

“Star came second.

He amused Nulyk, light tickled

For she was all and

Had never been touched

By another

She called him Hytl.”

Finally, there is L.P. Kindred’s science fiction poem “Stars Born Blue”, which is written like a creation myth for the universe by personifying stars and the blackness of space.

Nulyk, the blackness of space, was the first thing to ever exist in the universe until the first star, Hytl, materialised. They quickly fell in love, and their unions produced the many celestial bodies we know today: nebulae, asteroids, planets and more. But once Nulyk begins birthing suns, which glow blue when they are young, Hytl pushes them away from her so that they can learn to shine. These suns and other celestial bodies form clusters that make up the known universe, and crowd in the darkness.

As the heavens fill and get more crowded, Nulyk becomes lonelier. She has never produced anything that looked like her. She only sees herself, briefly, in the shadows her brilliant sons create as they shine upon their siblings. Hytl notices her suffering, but can only create a container for her pain: a thing he calls time. As time goes on, and as more stars scatter across the cosmos, she becomes their canvas, Kindred writes, but she forever connects them.

I loved this poem. I had never read a piece of science fiction poetry before, only witty poems about scientific concepts. Kindred’s ability to create myth from science was delightful to read, and it reminded me of other cosmologies, Hindu Cosmology about Rama opening Kristina’s mouth after he ate dirt and finding a whole universe inside. Astronomy has always been beautiful to me, and seeing it rendered so emotionally and richly in this collection was quite a delight.

Conclusion

There are many other stories in Voodoonauts Presents: (Re)Living Mythology. There are Mami Watas and Hags, tales of old gods and new powers. In all, this collection is an excellent display of what the future of speculative fiction can look like: a global community of authors from different cultures writing and re-examining their mythologies and making new things from them. I am excited to see what Voodoonaut’s future collections will look like, I hope to see more work by the Voodoonauts team and their students out in the world soon.

Do you want to learn more about the Voodoonauts Summer Fellowship? Check their website, https://www.voodoonauts.com/.

Want to read more work from the team? Check these out:

• Futureland: Battle for the Park by H.D. Hunter

• “And This is How To Stay Alive” by Shingai Njeri Kagunda (This short story was recently expanded into a novella)

• Reclaiming a Traditional African Genre: The AfroSurrealism of Ngano by Yvette Lisa Ndlovu

• “Your Rover is Here” by L.P. Kindred, read by LaVar Burton

You can scan the QR code below for links to these works: