By Stanley Greaves

To celebrate my 88th birthday on the 23rd of last month, I felt it would be good to share this history of the tenement yard, a cooperative environment that contributed much to my formative and subsequent years.

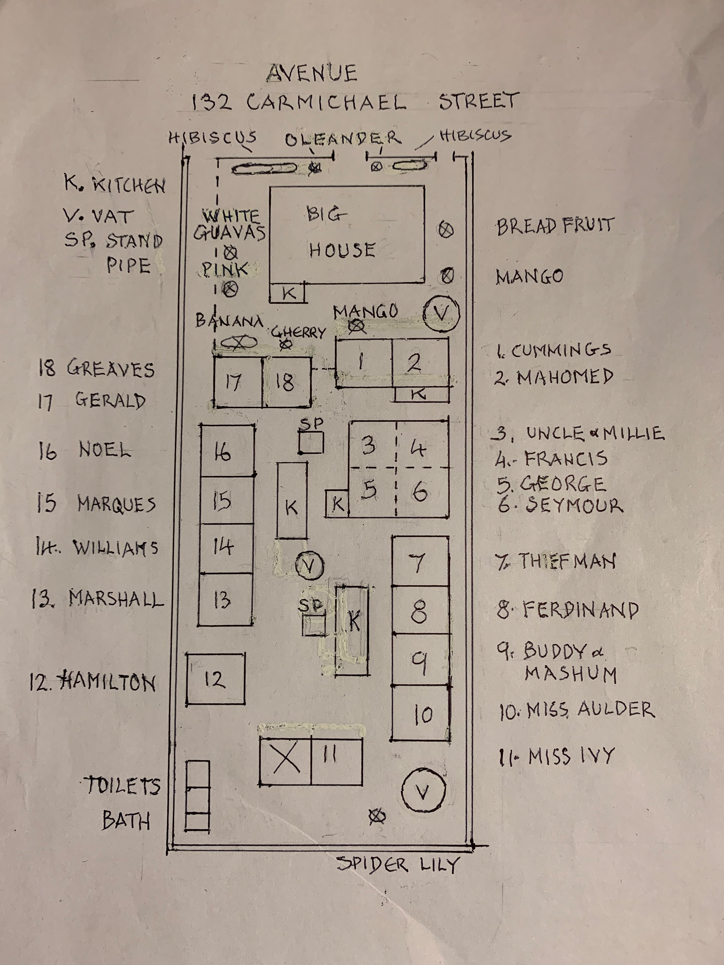

132 Carmichael Street was the location of a tenement yard on the eastern side of the street one lot away from Church Street on the south. I was born in the Georgetown Public Hospital to the sound of the six o’clock cannon in Kingston. A royal welcome but the only throne I ever occupied was a humble object found in working class homes that was given that honorific title. The cannon located in the Kingston Ward took the place of an alarm clock for the working class, signifying that it was time to “drink tea” ( bush tea with bread or Wieting and Richter “edger boy” biscuits, origin of the name is unknown) as breakfast was referred to and be off to work. Lunch was the midday meal, if one was available. I lived there with my parents John and Priscilla (familiarly known as Lydia) Greaves from age three and a half reaching seventeen in 1951 when we left. Three and a half is when my consciousness arrived faster than the speed of light and I immediately became aware of myself and parents. Years later it was my Mum who gave me the date when I described the event to her.

The yard occupied a long rectangular space. The landlord, Mr. Rankin, and his family of East Indian descent occupied the “Big House” in the front. The style was “vernacular” (commonplace) featuring a wooden two storied building with Demerara windows, wooden jalousies and fretwork eaves. Being perched on tall brick columns provided a high “bottom house,” where the open space between the front columns had lattice work. Inhabiting a small room in the bottom house was Mr. Daly, the yardman. He resembled Jack Johnson in the photograph my Dad had framed. Having a loud rough voice made him a dreaded figure, observed by children from a distance. At the front of the garden was a red hibiscus hedge and two white oleander shrubs, both sides of the main gate. Some of its “Y” shaped branches, which were cut by boys without permission, provided perfect forms for our slingshots. Flower beds of marigolds were surrounded by ceramic bottles that held stout imported from England. A smaller open second gate at the side provided access to a garage, which was later extended and divided to provide two rooms for rent. Over the gate extending inwards, a very short distance away, was an old arbour. The dried stems of coralita hanging from it were relics of a time when flowers graced the space and provided a sun lit dappled shade. According to my Dad, a few Portuguese families in the past tried to grow grapes in their gardens. Hearing this, forgetting the presence of Mr. Daly, I entertained myself imagining venturing into Mr. Rankin’s yard to pick grapes.

The tenement yard’s single entrance on Carmichael Street led to a narrow passage bordered by the landlord’s wire garden fence on the left. On the other side were the backs of houses and zinc fences of neighbouring yards. In one of those houses lived Mr. Miller, the tailor. I liked to visit him on errands for my Dad because if he was not there his children would entertain by offering me a spoon to dip into the Ovaltine tin. During the rainy seasons boards were laid to walk on because the passage became quite muddy. For boys this became a sporting venture. We walked heavily on some boards which created spurts of muddy water for us to dodge. This, of course, deepened cavities under the boards, which created problems for unsuspecting adults. Mr. Rankin and family after they moved into the tenement yard Big House avoided the muddy water hazard because they used the small gate between the two yard spaces and the other leading to the road. Another hazard faced when using the tenement entrance was the equivalent of running the gauntlet – a very ripe soft breadfruit, the size of a cannonball, falling from an overhanging breadfruit tree. It had the potential to be funny if you were an observer or a real nuisance if directly affected. Survival took the form of listening for the sudden rustling of the large breadfruit leaves and running like mad.

The tenement yard itself consisted of range houses, usually two or four to a range.

The only single room house was near the back of the yard. Rooms were all about the same size, roughly fifteen by fifteen feet, with the exception being the former garage and its extension. Occupants of rooms were mainly common-law couples, a few with children. The yard itself was like a village, meaning that privacy was at a premium. On the other hand help was extended to single individuals who became bedridden due to illness, like the flu or malaria.

Children belonged to the yard and could be disciplined verbally by anyone, especially Miss Aulder, the Matriarch of the yard. She was a tall “red woman,” past middle age, who wore long, plain earth-coloured skirts with a white long sleeved blouse, soft canvas shoes (commonly known as yachting shoes) and rolled down socks. Her ensemble was completed by a white head tie topped with a wide brimmed panama hat. As she strode through the yard, her eyes took in everything and she would intervene if any altercation, quite rare, ever arose. She was respected by adults and feared by noisy children. Both boys and girls bathed under the two standpipes in the yard until Miss Aulder announced to their respective parents that it was time their girls used the communal bath. Before a shower was installed a bucket of water had to be fetched. Boys used red Lifebuoy soap, girls used white Lux or pale green Palmolive. Lifebuoy was actually a germicidal soap and if this was known it was ignored.

The Big Yard had one large vat and the tenement yard had two, which were connected by zinc pipes to roofs to collect rainwater for cooking and drinking. One vat was in the middle of the yard, the larger one was at the far left in the yard and had a white spider lily plant growing near to it. Water from the standpipes came from the Shelter Belt plant on Vlissengen Road at the head of Church Street. The plant was connected to the Lamaha Conservancy, which supplied tea-coloured water. Government then set up a purification system to provide potable and drinkable water much lighter in colour. My Mum, however, in the evening used to sift a film of flour over the top of the water in a bucket and cover it. Next morning the water was crystal clear and used for cooking and making tea. The flour had settled, taking microscopic particles with it. Her technique, using flour as a flocculant, was correct. Years later, I learnt that the Shelter Belt used powdered alum to do the same work. Mum’s use of flour was cheaper. Tenants now had potable water but most still preferred drinking rain water stored in the vats. Use of water from this source was controlled by having the taps padlocked. If the water level was too low the wood would shrink, and exposed wood could even become dry rot.

During the rainy season a mosquito control officer in his khaki uniform and broad brimmed felt hat of the same colour inspected the vats to perform a little ceremony that fascinated me. He climbed a short ladder and removed a small sieve on the vat cover that kept out leaves and other debris. Using a long flashlight he would peer into the depths of water. From a small bucket he would scoop up small fish, known as millions, and release them in the water. I did not know why but later learnt that the fish ate malaria larvae to control the spread of malaria. Whenever I went to draw water I anticipated seeing fish enter into my bucket and was most disappointed when this did not happen, not realizing that they swam near the surface of the water where the larvae lived. In times of reduced rainfall, fortunately not often, the taps remained locked. Water for drinking and cooking had to be bought at a penny a bucket from the large metal storage tank situated south west of St George’s Cathedral. We had to walk carefully not to spill water. The shape of the bucket meant having to walk in a manner that looked funny to observers. For us it was a form of torture.

***

Shared facilities were two communal kitchens at the front and back section of the yard. Cooking pots and coal pots used for burning either wood or charcoal were made from cast iron and imported from the UK. There were two East Indian families who cooked on firesides created from clay mixed with dried cow dung to give it strength. Large forms to hold two pots incorporated two metal rods. They did not lose heat by radiation like cast iron pots and reduced cooking time. My Mum eventually asked the Mohamed family to make one for her to use in the cooking shed Dad had constructed. As the fire chief for the family, I found it easier to light and maintain the flame. The fireside itself was renovated by “daubing” -wiping fresh clay over it. Our cast iron coal pot was reserved for heating clothes irons.

The communal kitchen also provided a medical service. Smoke blackened cobwebs were used by us boys to stem blood from cuts in our feet which were the result sometimes from playing in grass along the Carmichael Street avenue which could contain pieces of “grass bottles.” Thinking of it now, the use of spider webs as an antiseptic could be an interesting research project in medicine. The other shared facility was the toilet and bathroom at the bottom of the yard. A bucket of water and a calabash for dipping were used for bathing, until a shower was installed. The door was usually kept closed to prevent rent free occupation by frogs and toads. Your towel and clothes hung over the door indicated it was being used.

Before my birth the Rankin family moved into what could be called the tenement yard “Big House” with his three children Peter, the eldest, John and Rita after his wife had died. The house was not as grandiose as the real “Big House” which was rented out. Stylistically the house was just a larger version of range houses in the yard. The walls made from imported pinewood called New York wood from the USA were covered with wallaba shingles. The weathering action of sun and rain turned them from dark red into shades of warm grey. The kitchen was a separate room adjoining the living room and overlooked the yard. Kitchens were designed that way because cooking was done on wood fired cast iron stoves, a potential fire hazard. The cook, Miss Ruby, from her shoulders upwards could easily be seen performing her duties. She is well remembered because when I was hospitalised with diphtheria she sent egg custard with my Mum. This was received with such great pleasure that I vowed to have custard daily when I began working – a promise never kept. On Sundays Mr. Rankin received rent from the inhabitants of the yard. I was tasked with delivering three dollars in an envelope to John and on rare occasions to Mr. Rankin himself seated in his rocking chair.

The western range of four rooms was divided into north and south by a narrow passage and the small gate mentioned used by the Rankin family. It was only my friend Colvin Stephenson and I who would venture to use it if open or climb over either to go play in the big yard to “raid” the fruit trees. Such activities only took place after Mr. Daly was somewhere else or later on when he had moved out. Trees in the garden receiving our attention were two mango trees of different species, either picked directly from the two trees or off the ground after heavy rainfall. The other trees were the pink lady and white lady guava trees and the rare Surinam cherry tree. Its fruits, with five rounded sections, resembled gooseberries — “goozaberries” as we called them — tasted just as sharp and astringent, really food for birds, but they made a fine jam. It was decades later in London that I saw gooseberries which bore no resemblance whatsoever in size, taste or form to our small “goozaberries”.

The Mohamed family, which occupied one of the northern rooms, were close friends with mine. Little Rehanna in particular was so close to my Mum that her Mum Bibi used to say “Miss Lydia, you are that girl’s mother not me.” In Guyanese parlance “She spirit mus’ be tek’ to you.” Some kind of spiritual attraction indeed must have existed between the two. I liked to encourage Rehanna to say cucumber, which came out as “cucumbumber,” which made me laugh. I was told by my Mum to stop making fun of her. Mr. Mohamed owned a dray cart which he sometimes stabled in the big yard. In the afternoon he parched peanuts to sell outside Astor Cinema. Loose nuts he sometimes gave to my Mum, who made nutcakes loved by all who received them.

Mr. Cummings, his old Aunt and Agnes, his young female cousin, occupied the room adjacent to the Mohameds. Agnes became my big sister. I was surprised and most distraught when Agnes died but got over it when Colvin Stephenson, another cousin, joined the family. We became close friends and playmates. An activity we loved was to create a cinema under his front step. A “borrowed” white sheet was the screen. Cardboard on the sides of the steps excluded sunlight. We showed scraps of film from the cinema which Colvin collected. Our clientele were friends who had to pay with buttons, a lucrative enterprise which provided us with buttons for marble games. When they became bored with seeing film scraps I began to paint things on pieces of glass using my Dad’s paints. The shoebox projector held whatever was shown at one end and a magnifying glass at the other. I sent a beam of light through the magnifying glass by using a mirror. Our business venture soon ended when the use of the bedsheet was discovered by Mr. Cummings’s irate Aunt. Colvin, who was very streetwise, got into trouble and was sent to the juvenile detention centre at Onderneeming. On his return I was regaled with tales about trips in the “bush” and chopping anacondas with a cutlass which would rebound off their muscular backs.

Mr. Cummings was the only person in the yard, apart from the Rankins, to own a radio. On Sundays it was turned up loud so others could share the broadcasts of Church services. It was the Classical Music program produced by Rafiq Khan which really held my attention. On one such occasion, when I was fifteen I heard Andres Segovia play Recuerdos De Alhambra, which sounded like a mandolin guitar duet. After hearing the announcement at the end, investigating how to play the classical guitar became an enterprise that still exists.

The small Big House the Landlord had moved into directly faced the western two room range, occupied respectively by the Cummings and Mohamed families. The “bottom house” was divided into four rooms. On the western side there was Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Francis, my St. Lucian Godparents who occupied one room. Uncle (never heard his full name) and Miss Milliecent or Auntie Millie the other. Where children and even teenagers were concerned, all non-family adults, even visiting strangers, were addressed as Uncle or Auntie. This “law”, respect for elders, a cultural product, was observed everywhere in the country and not just the yard. Adults even used the terms to refer to the elderly.

My Godparents lived at Sandhills on the Demerara River where Mr. Francis was a woodcutter and later foreman. Their room was used whenever they had to come to Georgetown on business. Even though I had studied French at Saint’s I did not understand their French Creole (pallawallah) but nevertheless loved the sound of it. Uncle was a hardworking person who like my Dad worked on the waterfront. He also mended or wove new fishing nets. I was fascinated watching a net grow as his hands, using two basic tools, the bobbin and flat measuring stick, created knots faster than I could blink. Because I like making things, to this day I am still fascinated watching artisans at work,

Occupying the eastern bottom house rooms were Mr. George and the Seymour family. Mr. George did odd jobs in between stints on the waterfront and always whistled while cleaned his bicycle on Sundays. Next to him was Mr. Seymour, the woodworker, who had the shortest laugh I have ever known. It consisted of two sounds, “He Haw,” when he was amused. Because of my habit of observing woodworkers, I could see that he was not particularly gifted. This feeling was further substantiated when I was sent most reluctantly to him for a haircut, his other job but only for clients in the yard. My hair was scraped by a razor and comb that always left my scalp feeling sensitive. From observing the results of my Dad sharpening his razor, I suspected that Mr. Seymour’s was not sharp enough. He lived with two grown sons and a much younger one nicknamed “Old Man” because of his looks. He responded to it, however, never complaining or looking hurt.

***

My family occupied one of the rooms on the southern part of the western range. Dad tried his best to make us comfortable by doing a range of odd jobs – tree trimming, sign painting, tattooing and rope mending, other than working on the waterfront as a general labourer. Our first next door neighbour, Mr. Barrow, was from Barbados and on weekends he would lock himself in with a bottle of rum. A little later came songs whose mumbled words in a Bajan accent made them unintelligible to me. He was followed by Mr. Gerard and family with two children. His wife was an East Indian from a West Coast village who had run away with him. Mr. Gerald was a short man with muscles in arms and torso so defined you could follow each strand. Such definition would have put muscle builders to shame. From his conversations I learnt he used to be a pork-knocker, having to paddle boats up river for days or even weeks on end to reach the goldfields.

Mr. Gerald was a devoted family man who also had a strong sense of community. Being aware of the muddy condition of the passage during the rainy weather, he collected funds from tenants and obtained spilled cement from his workplace. With the assistance of others the passageway was paved and extended to the communal toilets at the back of the yard. A major problem was that the front yard playing space for children was split up. We moved into the big yard for games, like “police and thief” and “bat an’ ball” (cricket with a tennis ball) and on occasion to the avenue for tennis games. Bats were homemade and balls were “obtained” by the favoured few who acted as ball boys at the nearby Bishops’ High School tennis courts. Mr. Gerald loved cricket and built a bench near to his home to engage cricket-loving individuals in conversations, especially during Test matches.

Opposite Mr. Gerald’s home was the southern north to south range. The Noel family, Aunt Netta, two adult sons and younger niece and nephew occupied the first room. The eldest son played football and later coached a ladies rounders team in the Parade Ground opposite the Promenade Gardens. Next to them was the Marques family, a mother, two sons, Maurice and Patrick, and Rita, their sister, who eventually married an American soldier and left for the USA. Patrick did help me a few times when I had problems with Arithmetic homework – long division. Mr. Williams and his wife were next. He was a sawmill worker in Charlestown who occasionally brought home offcuts to sell. I had lessons watching him use his axe to split and cut the wood. Cuts at right angles were to be avoided because wood could fly upwards and hit your face. He kindly lent me the Sunday Graphic newspapers to read the Tarzan, Prince Valiant and Mutt and Jeff Comic strips, among others. Last in that range were the Marshalls, a family with two boys, Noel and Raymond. Their father was from Barbados. Noel was a member of the St. George’s School Boy Scout troop. He took this activity quite seriously and I used to sit on my front step and observe him practising semaphore using flags. It was good to see him in uniform with his badges going off the meetings. He later studied electronic engineering in the UK, and on his return to Guyana installed modern telephonic equipment from Germany.

After the Marshalls moved out the room was occupied by the Munroe family, which included two girls who loved to play a certain game. Anytime I was seen making my way to the bath, either one would rush out to get there before me. What they didn’t know was that I had a small book in my pocket, the Gospel of St. Mark that I was studying for exams. I would sit on a rail in the fence and complete the assigned reading matter. They were really doing me a favour.

A short space led to the only single room in the yard occupied by Mr. Hamilton, a carpenter and his wife. A wide space separated his house from the communal toilet and bath at the back of the yard. He was a taciturn individual, who hardly spoke to anyone. I learnt how to sharpen saws watching him on weekends. He took his tools to work in a wooden box with a leather handle. The blade of his hand protruded on one side. A two room range ran north to south behind which was a zinc fence forming the eastern boundary. Miss Ivy, a huckster, occupied one room, the other was unoccupied. A dramatic event took place when police officers came and arrested her for receiving and selling stolen goods. We were sad to see her leave but she was released after a short stint in prison and continued working as if nothing had taken place.

The Northern range ran from east to west. The top room was occupied by Miss Aulder. The next family was East Indian, with a daughter. Buddy was the Father who had an unusual habit of brushing his teeth in public. His wife’s name, Mashoom, had a kind of magic to it. I felt it sounded like something from Arabian Nights. The next room was occupied by Alfred Ferdinand, a young bachelor who worked on the waterfront. He had a fine physique and boxed professionally as a middle weight. He was considered to be an upcoming champion, according to newspaper reports. I would read about fights, look at photographs and wonder what it would be like to attend matches to see him in action. Ferdinand always stopped to say something to me whenever he passed by and I began to regard him as a big brother. I was most distressed to learn that during his last bout he had slipped in the ring, hit his head hard on the canvas covered wooden floor and later died in the hospital. My distress was further heightened by the memory of the earlier demise of my “big sister” Agnes.

The last room was used by a gentleman. I used the term because unlike others he was not dressed as a labourer. Oh returning home he would lock his bicycle in his room. I often wondered what he did for a living. One day policemen came into the yard and headed for his room. A drama began to unfold as they knocked heavily on his door. We knew he was inside and waited to see what would happen when he opened the door. It remained closed so they broke it open. The man was nowhere to be seen. Reason was that he had made a trapdoor in the floor. The space under the range houses were quite close but manoeuvrable. As boys we often had to retrieve balls and even looked for eggs laid by hens that strayed. In addition, coins were sometimes found on the tops of floor beams. We boys were very careful not to disturb any sleeping many legged inhabitant.

The history of 132 Carmichael Street has to include a rental history of the Big House after it was vacated by the Landlord and family. During the years of World War 2 the place was an entertainment centre frequented by American servicemen. Some would come into the yard to buy food but were not successful. One even tried to buy a fowl cock from me. He did not press the matter after I told him it was my pet. One day we saw a few soldiers suddenly erupt into the yard through the small gate to disappear between buildings. Pursued by Military Police in white helmets they escaped through openings in wallaba railings into the next yard. We did not follow to find out if the soldiers were caught. For us boys it was a real version of our game of “police and thief’ but better still it was like having a front seat in the pit of Astor or Metropole cinema.

After the War the Big House remained empty for a while until it was rented by Richard Ishmael, to establish the Indian Education Trust. He also led a trade union for sugar cane workers to rival that led by the Jagans. I used to observe Brindley Benn, a former member of the PPP, holding classes sometimes on the paved section of the bottom house. The school was probably the first boarding school ever. A few boys who lived in the country used the top floor as a dormitory during the school week. I often wondered who prepared meals for them and if they were as tasty as home cooking.

Finally, the yard was where I learnt early on to make things from observing my Dad and to draw, which led to my total involvement with visual arts apart from a professional career in education. But that is another much longer story.

Many years later 132 Carmichael Street was acquired by the Government. All the tenement buildings were dismantled and the Big House was rebuilt and extended to become the Ptolemy Reid Rehabilitation Centre, named after the Minister of Health in the Burnham Administration. Seeing this for the first time and thinking of the compatibility that existed among former tenants, I uttered a silent prayer for the well-being of patients as well as administrative staff.