By Nigel Westmaas

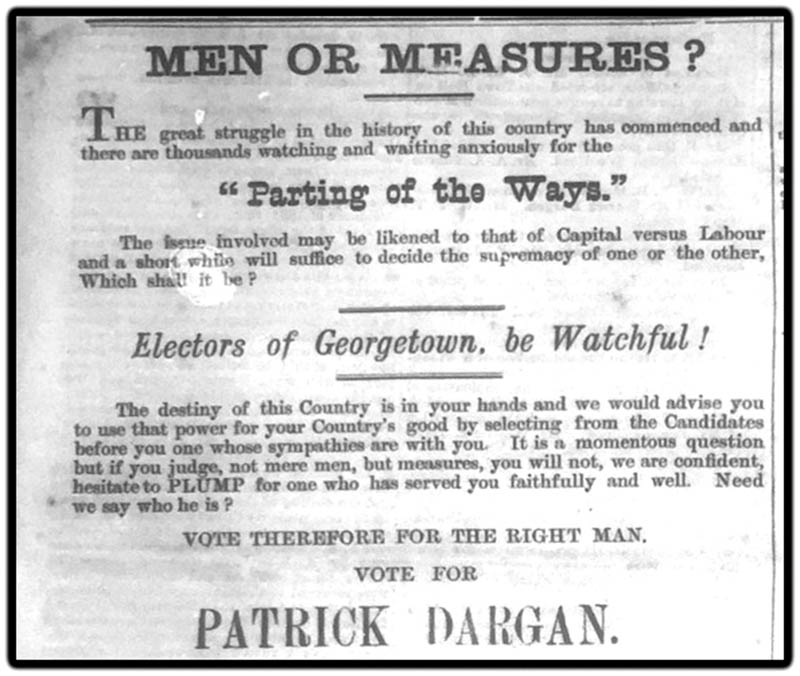

Patrick Dargan is accredited as Guyana’s first ‘formal’ non-white politician to occupy one of the highest rungs of government under the British colonial order, namely the Combined Court. Described as “the most dominant and fearless politician in his era” and celebrated as “Tribune of the People” and “national hero,” Dargan epitomised the era and the struggle to break the barriers of institutional racism amid a colonial order defined by the aristocracy of sugar. Described variously as a ‘Creole of mixed blood’, ‘mixed’ or black lawyer, Dargan became prominent, according to Walter Rodney (1981), after the political gains of the 1891 constitution, which gave “public spirited colonists their opportunity” and opened the possibilities for future black and brown (and mixed race) political aspirants.

As a legal practitioner Dargan also set the stage for other professionals entering the political realm in the restrictive colonial status quo. His occupations throughout his life resembled a gravitational pull of many causes and activities. Apart from his very visible political roles, Dargan was always on the circuit of social life in the colony. He was incredibly involved, for instance, in horse racing (he was a racehorse owner and Secretary of the D’ Urban Race Club) and one advertisement showed him placing a horse for sale. Dargan was also a Shareholder in the British Guiana Bank; held interests in the gold industry; was publisher of The Creole, and served as one-time chairman of the British Guiana Working Men’s Association (a union for clerks, mechanics and others).

DARGAN THE POLITICIAN

The political party that Dargan led was the middle-class dominated British Guiana Progressive Association (BGPA), established in 1896. The BGPA later absorbed the Portuguese-founded Reform Association, founded in 1889 (Dargan was also active in this group) and became a new force in the colony. In the 1897 general elections, the BGPA fielded several candidates, including Dargan, who won a seat as representative for southeast Essequibo.

But to understand Dargan the politician and activist it is necessary to provide a brief outline of the context in which he flourished. In the three decades in which he was active, there were incremental fluctuations in the British colonial system in which the planter class dominated amid the intersectional pillars of racism, and economic and social domination. In 1847 the Combined Court became the supreme policy body. There was ongoing turbulence in the colonial economy but by 1884 the crisis in sugar and the policy changes in the Combined Court signified a struggle between the erstwhile and ongoing planter class and an alliance of sorts between the Guyanese working people and the newly emergent black and brown middle class. But it took until 1891, as one of the changes, for the franchise to be extended, thus providing the conditions for Dargan to be elected to the Court of Policy on the Combined Court, thereby becoming the first black or brown person to hold a position on the policy body from 1894. Significantly, in 1896, the ballot box (secret ballot) as a means of voting was introduced for the first time on the colony.

In November 1906 Dargan (and others) again ran for a spot on the Court of Policy and won convincingly. The Creole newspaper, in the wake of his victory reported the following:

“Mr Dargan, standing on a box seat of a cab in America street, opposite to his chambers, addressed the people who numbered some thousands and who had gathered to learn of Mr Dargan’s victory. It was the largest crowd we have seen at the declaration of a poll and it was strong evidence of the popularity of the man who had worked hard for the last 12 years for the people of this country.”

Dargan in his own words summed up his own political career in a statement: “From the time I became a member of the Combined Court in 1894, up to the dissolution of the Court a month ago, I think I may safely say that I have discharged my duties fearlessly, faithfully and well. I have had no axe of my own or my friends to grind and have ground none. I have had no private interest to serve and have served none. I have, during the whole terms of office which I have held, had one interest, and only one, to serve, namely, that of the community in general, and I have, to the best of my humble ability, discharged that obligation. The work of representing the people of the colony, and you in particular, have always been to me a labour of love. My professional work, except on rare occasions, has been subordinated to yours, and if you see fit to elect me to represent you again, I promise to discharge my duties in the future as I have done in the past.”

But Dargan, despite his star quality, was not immune from controversy. He was cited in 1899 for impropriety in the transfer of a property and his case was taken before the High Court in a case described as one of the colony’s “famous trials”. It was not the only trial in which Dargan stood out. As an Attorney practicing in the courts from 1887 Dargan first came to prominence with his famous defence of another barrister at law, Louis de Souza who was charged for libel in the Royal Gazette newspaper. It is often deemed as one of the landmark cases in Guyana’s legal history.

DEVELOPMENTS IN WAKE OF THE 1905 REBELLION

It was during, and in the aftermath of the 1905 rebellion in Georgetown, that Dargan became even more prominent and an indispensable and fearless voice in the struggle against police officials, the economics of the colonial state and an active administrator in defence of the people.

And this fearlessness is seen in the ways in which Dargan challenged authorities from 1891 all the way during and after the impactful 1905 rebellion. His challenge was evident from several fora: letters to the press, court appearances in defence of the accused, on the streets, and in the Legislative bodies. He took up the cause, in the courts, of a black woman, Eliza Jones, who had been charged and convicted for the murder of Kishuny, an Indian woman at Plantation Melville in August 1905. Jones had been sentenced to death and while it was not unusual for a woman to be sentenced to this fate at the time, it was relatively rare, and her case had the press transfixed, especially as police misconduct and malpractice were figured in her “confession.” While barrister at law Sydney McArthur was Jones’ primary lawyer, the defence’s case was built around an attack at the level of the state. The misconduct of the police regarding her case occurred when Jones was forcibly made to kiss the Bible and confess in the presence of two police officials, including the notorious Inspector Lushington, at Brickdam Police Station. It was Dargan, other lawyers, and public criticism in the Creole newspaper that brought her case to the wider public attention.

The case even reached as far as the Secretary of State for the colonies – eventuating in her pardon and release from custody. The Creole later saluted the “chivalrous role played by the senior member of the Court of Policy for Georgetown, the Hon Patrick Dargan in espousing the cause of this poor friendless, and despised peasant girl.”

But it was Dargan’s vigorous defence of the citizens charged and convicted in the aftermath of the 1905 rebellion and his institution of charges against two notorious white police officers, Inspector Lushington and Major De Rinzey, that catapulted him into the almost daily news cycle. In May 1906, as fully reported in the Creole, Dargan as prosecuting counsel carried out a full-scale cross examination of witnesses to the shootings ordered by De Rinzey in the 1905 rebellion of the previous year. De Rinzey (who was charged with manslaughter) took the stand and was vigorously cross examined by Dargan. A fragment of a letter in the Creole 1906 summed up the behaviour of the British Guiana Police Force:

“As regards the British Guiana Police force this case proves beyond the shadow of a doubt that it has not yet reached that intellectual and moral place where it can appreciate and utilize as a basic factor in its acts the dictum that the police should be as much the friends of the prisoner as of the prosecution.”

Dargan later complained that people who were not charged were still photographed by the police in the wake of the 1905 disturbances and called for compensation for those injured.

In 1906 Dargan also moved a motion in the Combined Court for prison reform: “I beg to give notice that I shall move for a return for the year 31st August 1906 of all prisoners in the Colony whose sentences have been prolonged by the Inspector of Prisons, showing the names of the prisoners, their offences, the original term of imprisonment, the prolonged-term, and the nature of the misconduct for which the sentences were prolonged.”

LAND ACTIVISM FOR AFRICAN GUYANESE

Dargan not only dealt with transformative issues like the 1905 rebellion. He was simultaneously in the craw of the colonial authorities with other issues that subsumed the Combined Court. One of these was his advocacy, along with others, for land on behalf of African Guyanese. The so-called Dargan land scheme of 1906 was intended to settle African-Guyanese on the land and establish homesteads and place “motions for a commission to devise a scheme for settling black labourers on the land.” It was preceded by a Combined Court resolution he sponsored calling for a Commission of Enquiry for land:

“Whereas the chronic complaint of the people is that the Government will not assist them in cultivating the lands in the colony, and Whereas the number of unemployed is increasing, and whereas this court is of the opinion that the time has arrived when the Government should give suitable lands and build dwelling houses thereon with a view to inducing the people to settle on such lands and ultimately to acquire ownership of the same…”

Dargan clashed with several Governors – none more so than Governor Frederick Hodgson (1904-1911) on the condition of African Guyanese. In March 1906 Dargan severely reprimanded the Governor: “I find from your speech this afternoon that your Excellency does not care for the black man but the immigrant that comes here and the planter.” The Creole, for its part in the wake of Dargan’s criticism, lamented the Governor’s “well known indifference to the claims of the negro inhabitants of this colony,” labelling the Governor a “negrophobist of the most aggressive type.” So belligerent was Dargan’s advocacy that a manager of Plantation Schoon Ord, a “Mr Leslie,” derisively told a group of black workers to “go to Dargan for work for he is the only fool in the Colony who is speaking against the whites.”

In spite of his concentration at the time on the African Guianese conditions Dargan on occasion also questioned the treatment of Indian indentured labourers, at one point posing the following question: “Were the indentured immigrants sent to prison by Skeldon magistrate for offices committed under immigration laws made to walk from Skeldon to New Amsterdam?”

DEATH

The pithy information available in the records on Dargan’s private life indicates that he was married to Maria Judith Dargan, formerly of Dulwich, England, and that Dargan’s second son, Frank Dargan, who followed him into the legal profession, and was set to follow his father into politics, passed away in 1916.

Dargan passed away at the relatively early age of 58 in 1908. His funeral was one of the largest in the colony’s history and described as “huge and overflowing,” with the Dominica Guardian newspaper estimating the size of grievers at 8,000.

Because of his renowned oratorical ability in the courts, on the political hustings on the street, the Court of Policy, and his life’s contributions, a debating award called the Dargan Debating shield for inter-club debating was established at Queen’s College for this early Guyanese politician. Patrick Dargan’s House, built in the 1880s and commonly known as Dargan’s House is located at Lot 90 Robb and Oronoque Streets, Georgetown. Dargan also lived at 6 America Street.

Dargan’s imprint on Guyanese politics in the twentieth century was profound and influenced other black and brown Guyanese politicians, including AA Thorne, ARF Webber, Nelson Cannon, AB Brown, and even politicians of later vintage.

As historian and politician ARF Webber wrote, Dargan’s enduring popularity overshadowed everyone in the “imagination of the people.”