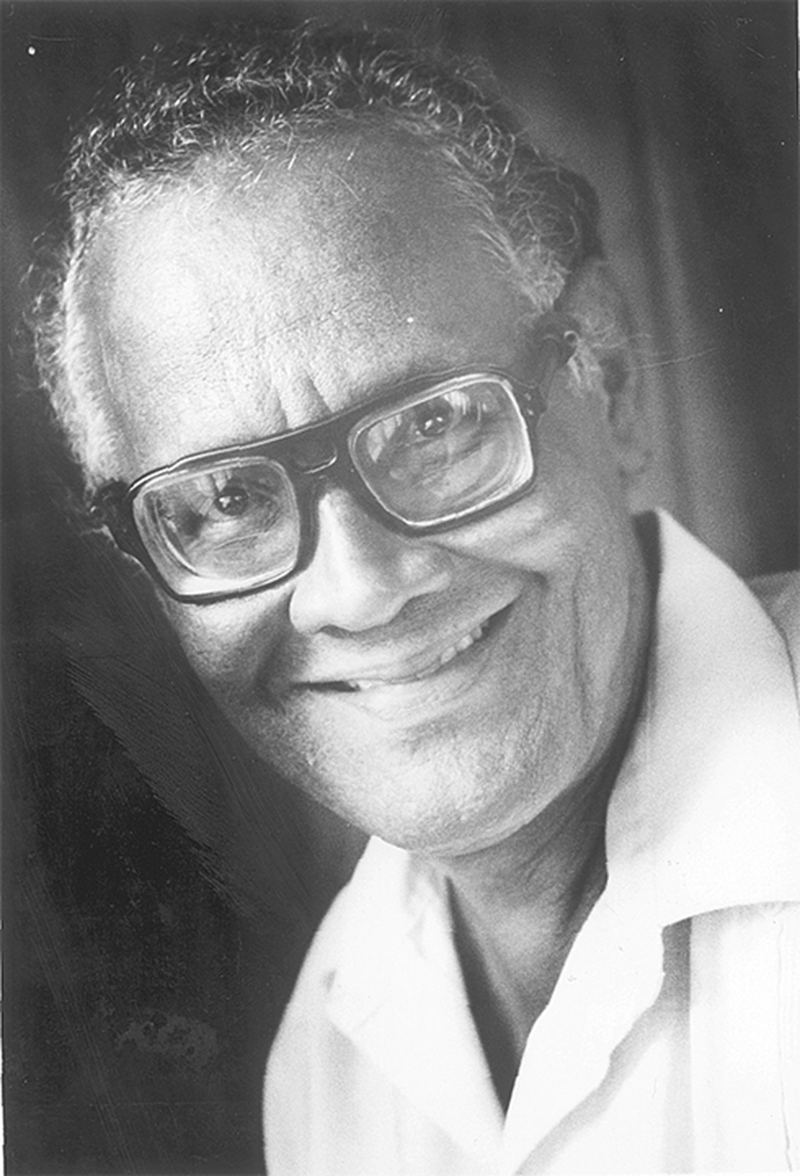

To mark the 25th anniversary of the passing of Martin Carter, Gemma Robinson spoke to Nicholas Laughlin from Alice Yard, an art collective in Port of Spain, about art, activations, and a project linking writing and drawing with Carter’s work at the heart of it.

How would you draw a poem? This was one of the invitations offered by the Port of Spain-based art collective, Alice Yard, this year in a global art initiative that culminated in a 100-day exhibition in the German city of Kassel.

Documenta happens every five years, and in 2022 was curated by the Indonesian collective, ruangrupa, who encouraged over 60 art collectives from around the world to bring their work and way of working to Kassel. For Alice Yard, a collective inspired by ‘communal urban yard spaces and mas camps’, that meant creating a combined living and exhibiting space in the centre of Kassel to host a series of residencies and ‘spontaneous activations’ for artists and audiences visiting the space. I spoke to Nicholas Laughlin, one of the co-directors of Alice Yard, about Martin Carter’s place in this vision of art as collective practices of sharing, the gathering of communal resources, and sustainable collaboration.

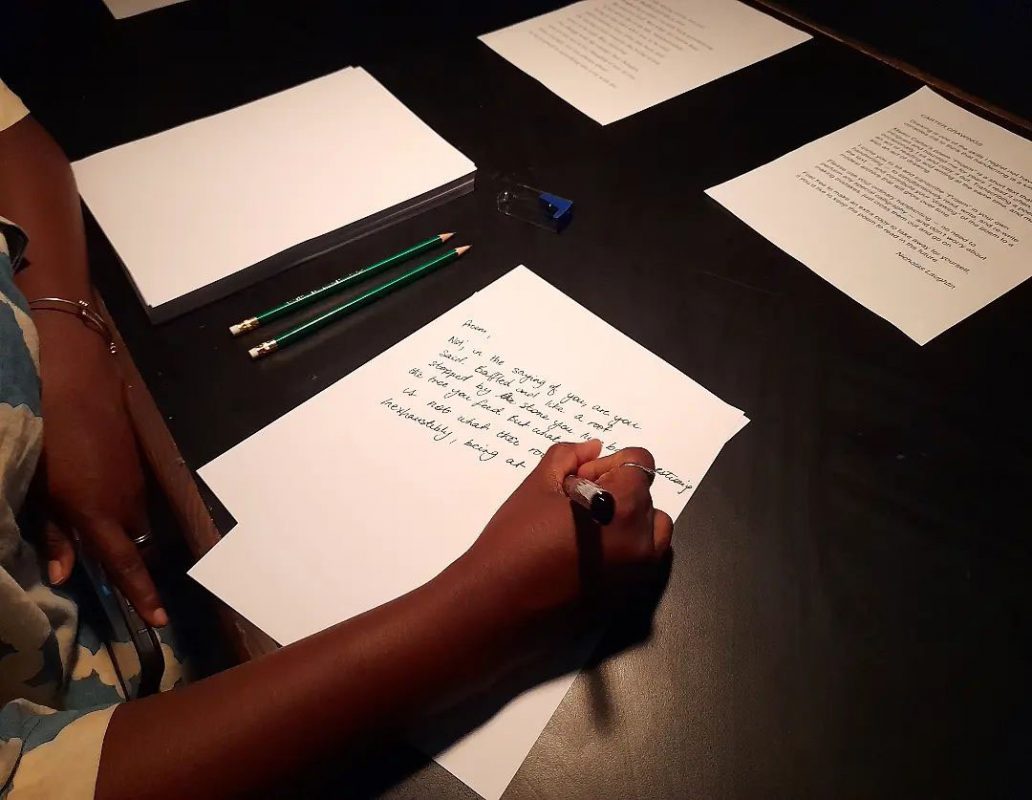

As the writer and editor in the collective, Nicholas (who you might also know as the former editor of Caribbean Airlines’ magazine, Caribbean Beat, or as the current Director of the Bocas Lit Fest and the author of two collections of poetry) knew that Carter was going to feature in some way. An initial idea for a book project was shelved as the budget shrank, but writing remained central. Planning a poetry event in July this year in Port of Spain, they had already worked out an activation by the artist Marlon Griffith, called ‘Score for a Procession’, that asked people to draw while listening to their heart beat. Another involved a travelling book created by an Argentinian collective inviting people to annotate it. As they were thinking about a third, Nicholas remembered: ‘For years I’ve had a vague idea of doing some kind of project where I ask people to sit down and copy out the same text. What happens when 10 people, 100 people, 1000 people perform that simple action?’ He almost didn’t find out, thinking the idea was a bit ‘half baked’, but when Martin Carter’s poem ‘Proem’ came to mind he decided to try the experiment.

Visitors to Alice Yard’s art space, Granderson Lab, were given these brief instructions:

Drawing is one of the skills I regret not having. But it consoles me to think that handwriting is a kind of drawing.

Martin Carter’s poem “Proem” is a short text that has intrigued and haunted me for years. I read it often, and occasionally I sit and copy it out.

Transcribing a poem is an act of reading and writing at the same time, and maybe also an act of drawing. I invite you to sit and transcribe “Proem” in your own handwriting — to simultaneously read, write, and re-write the text — and contribute your “drawing” of the poem to a modest archive that will grow over time.

To Nicholas’s surprise the invitation proved popular at the event: ‘So I thought, let’s try doing it in Kassel, because it’s very easy to set up. You literally need just paper and a pen’. Again the ‘Carter Drawings’ activity was popular – over 700 people in the German city took the time to sit and write out the entire poem, more completed partial copies – and Alice Yard have a growing archive that could soon reach 1000. In Kassel people were queuing up to ‘draw’ the poem. Nicholas recalls ‘there were times when I could barely walk down the corridor where the activation was placed, because it was so full of people. In the space that was meant for one person, two people were writing at the same time and three people were crowding around waiting to do it’.

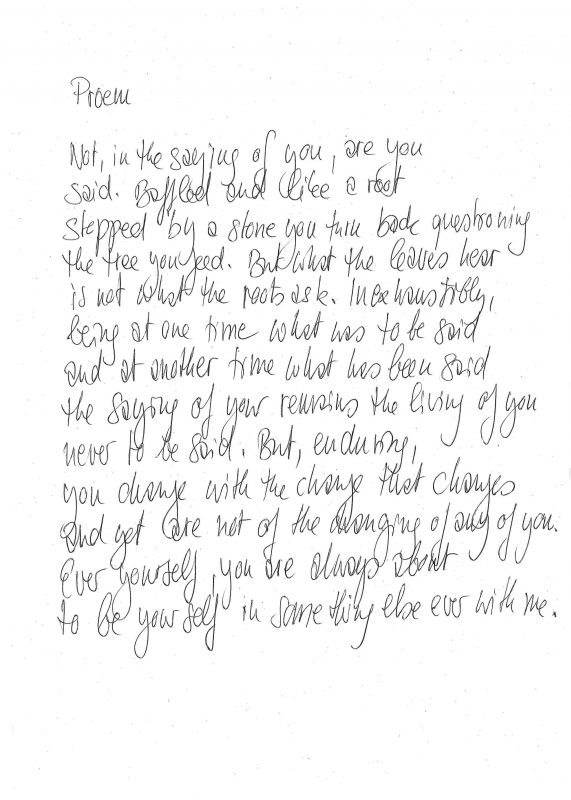

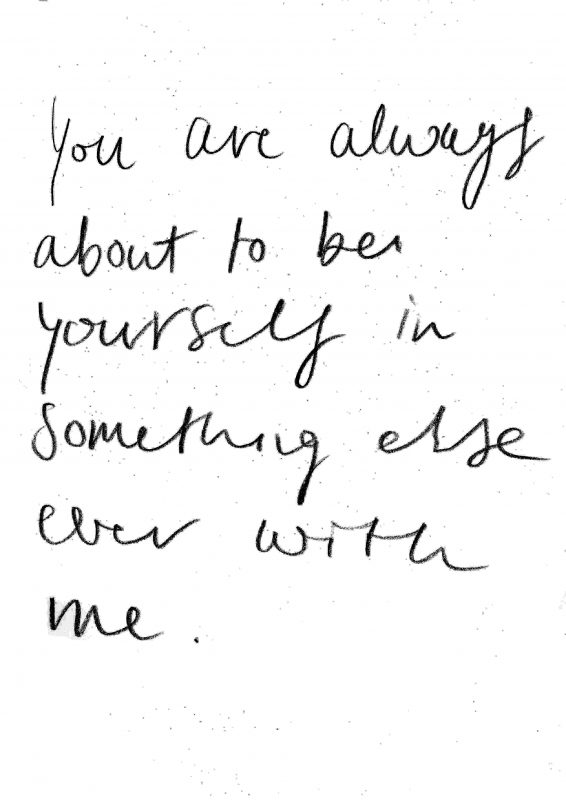

Part of the appeal of ‘Carter Drawings’ was that it matched the spirit of this year’s documenta and its hope to create communal art spaces and see everyone as active makers, not just consumers of art. Nicholas also feels that that his activation might have removed some of the barriers that people can feel about creating, the feeling he says of ‘I don’t think I could do a drawing, but I could sit down and write this out’. The task can be as simple or as complex as you like. And the contributions are fascinating. You might expect one poem to look like another but in the A3 posters that group together some of the poems what is revealed is the everyday artistry of people’s handwriting, and an intimate creative commitment to spending time with the poem. For some that meant following the poem word by word. Others ignored Carter’s lines to make a new layout. One person wrote out a quotation (‘You are always about to be yourself in something else ever with me’) in a flowing hand. Another borrowed the ink and paintbrush set out for Griffith’s ‘Score for a Procession’ and carefully painted Carter’s poem. Someone else sketched a person writing out the poem with the title ‘She is doing Proem’.

These individual, idiosyncratic moments of concentration are a special kind of paying attention, and they also connect to Carter’s own poetic practice. Even in his earliest work we can see this. In ‘To a Dead Comrade’ Carter encourages himself and those experiencing loss to ‘take / a patience and a calm’. ‘Proem’ was written in 1974 and comes from a later body of work, The When Time, a series of new poems that were first published in Poems of Succession. But the poem also has a stand-alone quality, appearing at the start of the book and prefacing a collection of poems that brings together Carter’s work from the 1950s, 60s and 70s. It’s a perfect introduction to Carter in many ways. But for Nicholas it is more than that:

I think ‘Proem’ is a perfect poem [for this activation] because you have to concentrate — the sentences are tricky, they trip you up. You can’t be half-hearted or distracted when you’re doing it, but it’s also just the right length to give you a 5-to-10-minute break. There’s a kind of an economy. But at the same time, it’s also one of those things where it’s like something has happened here to the laws of physics. How can there be so much packed into such a small space? It’s one of those poems where every word matters in the space where it is. And honestly, that’s not the case of every poem!

The poems written out on the blank A4 pages reinforce this economy and the ‘Carter Drawings’ activation starts to show us how the simplicity of repetition (Nicholas calls it ‘the conscious intimacy of transcription’) is also a kind of striking complexity.

The idea of repetition is also written into ‘Proem’. It opens with the words: ‘Not in the saying of you are you / said’. Tightly composed in thirteen lines, and one line short of a sonnet, the poem encourages us to think about articulation, identity, mutability and collaboration. Nicholas says, ‘I tend to read ‘Proem’ as a metaphysical dialogue in which “you” and “me” are simultaneously, the poet, the poem and the poem’s reader (who is also the poem’s writer)’. If that sounds complicated, it is, but satisfyingly so. The poet’s constant failure or resistance to grasp its unnamed subject is expressed as each line slips into another attempt to locate the indefinable ‘you’. There is also pleasure here: a symbiotic relationship between ‘you’ and ‘me’ can imply the rapports of love poetry. But as Nicholas implies the ‘you’ and the ‘me’ of the poem are positioned for each reader to unravel. And this adds a further dimension to the ‘Carter Drawings’ activation, as each reader has to become the writer of the poem – if only for a few minutes.

Martin Carter’s work has always travelled short and long distances and found new homes for new times and in new voices. From the poems he shared with friends and comrades in the Georgetown living rooms of political activists in the 1950s to the solidarity readings of his work by the West Indian Independence Party in Woodbrook Square in Port of Spain, to the publication of Poems of Resistance from British Guiana in London by Lawrence and Wishart. Jan Carew and Sylvia Wynter took one of Carter’s most famous poems as the title for their 1960s radio play, The University of Hunger. Andaiye and Walter Rodney found room for Carter’s poems as the headings to the chapters in Rodney’s History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905. Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s 1986 book, Decolonising the Mind, invokes Carter as a starting and ending point for his thinking.

The list continues. Stanley Greaves has a long-standing appreciation of Carter’s work that crosses his visual and poetic work. Linton Kwesi Johnson recorded Carter’s Shape and Motion poems for his 1998 LP, More Time. Gordon Rohlehr’s collection of essays is titled with a striking line from Carter: My Strangled City. The band, 3Canal, found musical solace and energy in Carter’s 1950s political ‘emergency’ experience in their 2006 production, Caribbean Imperia, and again when Trinidad experienced its own ‘emergency’ lockdowns in 2011. Anthony Vahni Capildeo’s plurilocal responses to Carter have animated both their poetic and performative work. Hannah Kendall’s production, The Knife of Dawn (2016, 2020), incorporates Carter’s poetry to imaginatively recreate his hunger strike as one-man opera.

The ‘Carter Drawings’ activation shows us once again how Carter’s work continues to travel and find relevance today. Nicholas notes that ‘activation’ was a word used a lot in documenta 15. It sits between ideas of activity and invitation and emphasizes creative processes that are inclusive, participatory and experimental. The word also serves as a reminder of Carter’s own activism, an activism that was often focused on provoking questions about community, and one that ranged across political party action, resistant protest, writing open letters, and everyday conversation.

So what happens next for ‘Carter Drawings’? Nicholas sees it as open-ended and ongoing. Most recently it appeared again in London in November at an event called Hackney Nonkrong. Picking out the Indonesian word for hanging out, Alice Yard were following the vocabulary used in documenta 15 and its interests in ‘expanding the way language is used … as a tool to develop new ideas and perspectives’. ‘Proem’ is an open invitation to do just that, and the Alice Yard activation encourages us to draw, write and read our way to a new understanding. And you don’t need to wait for a new nonkrong, you just need a piece of paper, a pen and ten minutes of concentration.

Alice Yard invite anyone to join in the ‘Carter Drawings’ activation. For details see: https://aliceyard.blogspot.com/p/carter-drawings.html

Gemma Robinson is the editor of University of Hunger: the Collected Poems and Selected Poems of Martin Carter (Bloodaxe).

Proem

Not, in the saying of you, are you

said. Baffled and like a root

stopped by a stone you turn back questioning

the tree you feed. But what the leaves hear

is not what the roots ask. Inexhaustibly,

being at one time what was to be said

and at another time what has been said

the saying of you remains the living of you

never to be said. But, enduring,

you change with the change that changes

and yet are not of the changing of any of you.

Ever yourself, you are always about

to be yourself in something else ever with me.

(First published in the Guyanese journal, GISRA, in 1974 as ‘Ever with Me’ and then republished in Poems of Succession (London and Port of Spain: New Beacon, 1977).)