Accepting gifts, honours and favours in connection with official duties may give rise to a real or apparent conflict of interest, as it may be seen to create an obligation. Accepting gifts, honours or other tokens of appreciation can impact our independence and impartiality…Staff members carrying out functions in sensitive areas such as procurement and investment management must be particularly attentive to this risk; they are held to an even higher standard, in relation to the discharge of their duties and responsibilities.

Accepting gifts, honours and favours in connection with official duties may give rise to a real or apparent conflict of interest, as it may be seen to create an obligation. Accepting gifts, honours or other tokens of appreciation can impact our independence and impartiality…Staff members carrying out functions in sensitive areas such as procurement and investment management must be particularly attentive to this risk; they are held to an even higher standard, in relation to the discharge of their duties and responsibilities.

United Nations Ethics Office

The Chairperson of the Grenada’s Citizenship by Investment Programme Unit, Richard Duncan, returned a gift to a Chinese businessman who was granted Grenadian citizenship. The gift comprises EC$10,000, a bottle of drink and other items. In a letter to the businessman, Mr. Duncan and the Chief Executive Officer stated that:

The value of the above-mentioned items is incongruent with the Grenada Citizenship by Investment Code of Business Conduct and Ethics Policy; therefore, these items cannot be accepted. Additionally, as stewards of the public trust, we are sensitive to ensure adherence to the integrity in Public Life Regulations as well as the Prevention of Corruption Regulations, as it relates to gifting.

I recall my own experience in the early 1990s when I returned an expensive bottle of whisky to a contractor who was being investigated for sub-standard work performed. Staff members were also warned against the accepting of gifts, including hospitality, without first discussing the matter with me. Later, I had attended a course on the economics of corruption in Germany, where I raised the issue of gift-giving. It created an uproar in the class of young PhD students, some of whom were adamant that this practice is an integral part of the cost of doing business. The issue is indeed a sensitive one, as in some cultures gift-giving is an established norm. Therefore, the refusal to accept them would be frowned upon and can affect relationships.

During my stint at the United Nations, I was presented with two vases which I accepted for office use, later to be inventorised. This was in keeping with UN Administrative Instruction ST/AI/2010/1 that allows staff members to accept on behalf of the Organization, without prior approval from the Secretary-General, minor gifts of essentially nominal value. All other gifts can only be accepted with the approval of the Secretary-General and turned in to his/her office for safekeeping and subsequent disposal in accordance with the approved procedures.

Also in the news, the Trinidad and Tobago Integrity Commission served court orders on hundreds of public officials in 2022 for failing to declare their assets. However, 37 persons failed to comply, resulting in their files being sent to the Director of Public Prosecutions. Every year the Commission publishes the names of defaulting public officials, urging them to file their declarations. See https://trinidadexpress.com/news/local/integrity-commission-takes-action/article_3d0ce854-889d-11ed-9d3b-975f5e2fd22f.html. The Guyana Integrity Commission needs to get its act going, especially as regards: (i) arranging for the prosecution of public officials who have failed to submit their financial declarations; (ii) investigating apparent mismatch between declarations and ownership of assets (inclusive of beneficial ownership) as well as observable lifestyles; (iii) conflicts of interest; and (iv) violations of the Code of Conduct.

Today’s article is our fifth article on the 2021 Auditor General’s report on the public accounts. So far, we have dealt with the certification of the consolidated financial statements constituting the public accounts; the highlights of the report; financial and budgetary performance; the Contingencies Fund; the Deposit Funds; Schedule of Outstanding Loans; and the Stores Regulations.

Current assets and liabilities of the Government

One of the financial statements comprising the public accounts is the Statement of Current Assets and Liabilities of the Government and not “Assets and Liabilities of the Government”, as stated in the Auditor General’s report. The key difference between the two is that fixed assets, receivables, inventories, payables and long-term liabilities are not included in the former, compared with the latter. This is mainly due to the use of the cash-basis of accounting for recording and reporting financial transactions of the Government. In several of our columns, we pointed out the limitations of this system of accounting that focuses mainly on cash and cash equivalents, almost to the exclusion of all other forms of assets and liabilities. As a result, the reporting of the Government’s financial condition remains incomplete. Over the years, the system was subject to significant abuse and major violations, as reflected in successive reports of the Auditor General, without evidence of sanctions being imposed on the concerned officials.

In 2016, the Government had decided to adopt the accrual-based accounting system consistent with the International Public Sector Accounting Standards. This requires full financial reporting similar to that which prevails in the private sector. Phased implementation was to have taken place since then. However, little or no progress has been made so far, and it is unclear whether the project has been shelved, as the Minister of Finance’s budget speech for the last three years made no mention of this. By Section 56(1) of the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act, the Minister is required to ‘promulgate accounting standards to be employed by officials responsible for the maintenance of the accounts and records referred to in this section’.

The Statement of Current Assets and Liabilities as at 31 December 2021 showed a net liability of $97.771 billion, compared with a net liability of $242.942 at the end of 2020, a decrease of $145.171 billion. This reduction was mainly due to the liquidation of the overdraft on the Consolidated Fund, which stood at $207.078 billion as at 31 December 2020. Funding for this was provided through the issuance of new Treasury Bills as well as debentures. Treasury Bills are a form of short-term borrowing whose maturity date is 12 months or less; while debentures have longer timeframes for maturity, usually 10 to 15 years, and are used to raise capital, especially for large infrastructure works.

It is not normal for long-term borrowing to be used to reduce or liquidate an overdraft, as such action is in effect substituting a short-term liability with a long-term one. It therefore does not represent an improvement of the financial condition of the Government.

The overdraft was held at the Bank of Guyana, and did not attract interest charges by virtue of other government deposits being held by the Bank for which no interest is payable to the Government. In the circumstances, it might have been more prudent to progressively reduce the overdraft and eventually liquidate it using a portion of the oil revenues from the Natural Resource Fund (NRF).

In its 2022 Article IV Consultation Report, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) called for a measured increase in spending on public investment to ensure that the annual non-oil overall fiscal balance does not exceed the expected oil transfers. The revised estimates of expenditure for 2022 is $645.0 billion, while anticipated revenue collections amount to $466.954 billion, giving a budgetary fiscal deficit of $178.046 billion. This deficit would exceed the G$126.694 billion that was transferred in three tranches from the NRF to the Consolidated Fund. Taking into account these transfers, the budgeted fiscal deficit for 2022 remains at $51.382 billion. In 2021, when there was no transfer of oil revenue, the budgeted fiscal deficit was $86.046 billion. That apart, all transfers from the NRF should be treated as revenue to be matched with expenditure to arrive at the actual fiscal surplus or deficit for the fiscal year in question.

Schedule of Government Guarantees

The FMA Act defines a Government guarantee as a contingent liability that is an obligation undertaken by the Government to pay the debt of a third party in the event that the third party defaults on its debt obligation. The Act also defines a contingent liability as a future commitment, usually to spend public moneys, which is dependent upon the happening of a specified event or the materialisation of a specified circumstance.

Section 3(1) of the Guarantee of Loans (Public Corporations and Companies) Act authorizes the Government to guarantee the discharge by a corporation or a company of its obligations under any agreement which may be entered into by the corporation with a lending agency in respect of any borrowing by that corporation which is authorized by the Government. The aggregate amount of the liability of the Government in respect of guarantees is not to exceed $1 billion. On 7 August 2013, the National Assembly approved of the limit to $50 billion to facilitate the Power Purchase Agreement between the Guyana Power and Light and Amaila Falls Hydro Inc. However, since 2015 the Amaila Falls Project has been put on hold. The present Administration plans to resuscitate it.

The Schedule of Government Guarantees at the end of 2021 shows one guarantee in the sum of $500 million relating to the Bank of Guyana’s contribution to the Deposit Insurance Fund.

Schedule of Contingent Liabilities

The general principle for the recording of a contingent liability relates to the probability of occurrence of an event. If such probability is remote, then the transaction is a contingent liability. If there is a possibility that the event will crystallise out, then financial prudence will dictate that the transaction be recorded as an actual liability.

The Schedule of Contingent Liabilities is the same as that reflected in the Schedule of Government Guarantees.

Statement of Public Debt

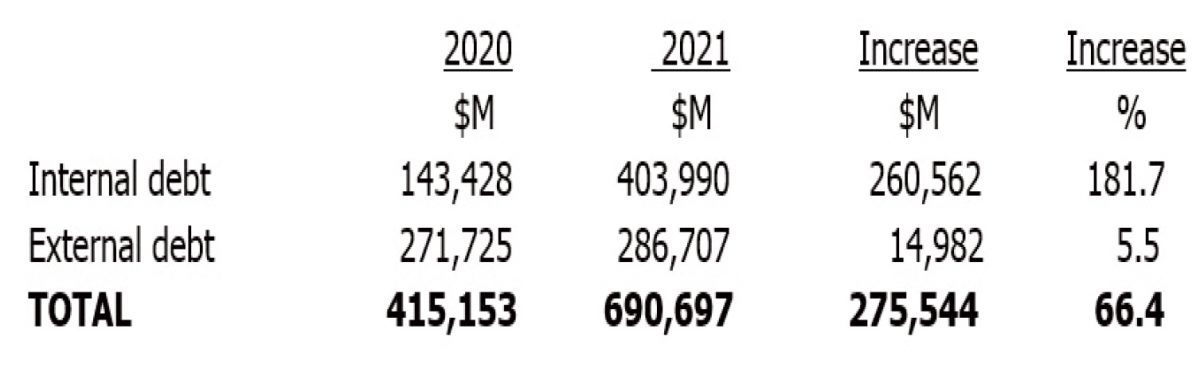

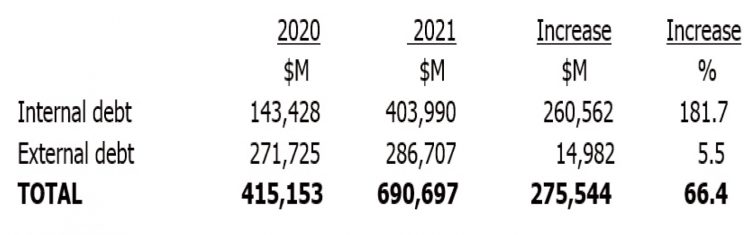

At the end of 2021, the public debt stood at G$690.697 billion, compared with G$415.153 billion at the end of 2020, an overall increase of G$275.544 billion, or 66.4 percent. This increase was mainly due to a significant increase in the internal debt from $143.428 billion in 2020 to $260.562 billion in 2021, representing a 182 percent increase, as shown below:

Treasury Bills outstanding at the 2021 amounted to $146.508 billion, compared with $80.944 billion, an increase of $65.564 billion. Debentures have also increased from $7.805 billion to $205.560 billion, mainly due to the issuance of five sets of variable interest rate debentures totalling $200 billion, with repayment periods ranging from one year to 20 years.

Treasury Bills outstanding at the 2021 amounted to $146.508 billion, compared with $80.944 billion, an increase of $65.564 billion. Debentures have also increased from $7.805 billion to $205.560 billion, mainly due to the issuance of five sets of variable interest rate debentures totalling $200 billion, with repayment periods ranging from one year to 20 years.

In equivalent United States dollars, the external debt was US$1.375 billion, compared with US$1.303 billion at the end of 2020. The Exim Bank of China accounted for six loans totalling US$240.451 million, representing 17.5 percent of the external loan portfolio. Last week, the Authorities announced the signing of two loan agreements with the China in the sums of US$192 million and US$172 million for East Coast Demerara road expansion project and the construction of the New Demerara Harbour Bridge, respectively.

With these two loans, Guyana’s indebtedness to China is set to overtake the 20 percent incurred by Sri Lanka which is currently in a state of severe economic crisis after years of economic mismanagement combined with the COVID-19 pandemic. The latter is undergoing a restructuring of its debts and is in negotiation with the IMF. See https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/sri-lankas-debt-china-close-20-public-external-debt-study-2022-11-30/#:~:text=The%20island%20nation’s%20total%20external,22%25%20is%20from%20Chinese%20creditors. In December 2017, the Sri Lanka government handed over to China the Hambantota Port, including 15,000 acres of land around it, for use for 99 years. The Port was constructed by China Harbour Engineering Company with financing from China’s Exim Bank. See https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/25/world/asia/china-sri-lanka-port.html.

The Sri Lanka’s experience has important lessons for Guyana since the incurrence of excessive debt, both internally and externally, can adversely affect the economy. While Guyana’s medium-term economic prospects appear very favourable due to anticipated oil revenues, the authorities should nevertheless exercise restraint in Government spending, given the volatility of oil prices. And, with global warming and climate taking their toll worldwide as well as the effects of the war between Russia and Ukraine, who knows what the future holds for the oil industry? Considering this, the Government needs to intensify efforts aimed at ensuring that the economy is sufficiently diversified. After all, in the Guyanese context, it is the performance of the non-oil economy that makes the real difference in the lives of ordinary citizens.

Conclusion

While the Auditor General is up to date in the auditing of central government activities, the quality of his audit and reporting of the results can be improved significantly if comprehensive quality assurance procedures are adopted. These procedures ensure that: (i) the audits are conducted in accordance with approved audit plans and detailed audit procedures based on risk assessments, are carefully followed; (ii) the findings are supported by adequate audit evidence and are properly formulated; (iii) the recommendations are concise and precise, and follow the SMART ( simple, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound) approach; and (iv) the overall conclusions in the form of certification of the accounts are carefully crafted in accordance with the International Standards of Auditing.

The Auditor General needs to reflect on the impact of his reports which are unwieldy in terms of size and content, and are substantially a copy and paste of the contents of the previous report, with appropriate amendments. Some of the findings are also not material to the proper presentation of the public accounts and are essentially in realm of internal audit. Additionally, consideration should also be given to a revised reporting format. The present reporting template has been in place since 1992.

In our next article, we will examine the financial reporting and audit of non-central government entities that are part of the wider public sector and for which the Auditor General has audit responsibility.