When I began this weekly column last October, the discussions focused on the elements of art and the principles of design. My goal was to introduce the basic ingredients needed to make art. These are the very tools – if you will – to understanding art. As a consequence, I introduced the essential building blocks of a formal analysis of a work of art – one of the ways of critically analysing a work of art. I tried to show that by looking at how the elements of colour, line, shape/form, texture, space, and light are used, one can gain insight into a work of art and maybe gain an appreciation of it. The same is possible when considering the principles of design – balance, emphasis, scale and proportion, repetition and rhythm, unity and variety, and contrast. By the end of the ten weeks of these discussions, it should have been evident that a conversation with the artist is not necessary to have a relationship with a work of art. Therefore, there is no need to seek out the artist to have him or her tell you about the work. Also, there is no need for you to feel lost or confused if the artist is not present to tell you about the work. In fact, you may have more insight into the work than the artist. It happens.

When I began this weekly column last October, the discussions focused on the elements of art and the principles of design. My goal was to introduce the basic ingredients needed to make art. These are the very tools – if you will – to understanding art. As a consequence, I introduced the essential building blocks of a formal analysis of a work of art – one of the ways of critically analysing a work of art. I tried to show that by looking at how the elements of colour, line, shape/form, texture, space, and light are used, one can gain insight into a work of art and maybe gain an appreciation of it. The same is possible when considering the principles of design – balance, emphasis, scale and proportion, repetition and rhythm, unity and variety, and contrast. By the end of the ten weeks of these discussions, it should have been evident that a conversation with the artist is not necessary to have a relationship with a work of art. Therefore, there is no need to seek out the artist to have him or her tell you about the work. Also, there is no need for you to feel lost or confused if the artist is not present to tell you about the work. In fact, you may have more insight into the work than the artist. It happens.

Of course, analysis of how the elements and the principles are used within a particular work of art may not lead to the formation of a good relationship with it. It is possible that such an analysis may lead to loss of appreciation for something once appealing. Not surprising. We know the same is possible with human relationships. Indeed, the instantaneous attraction to a lovely shape may be lost once the holder of the shape begins to speak and it is realised little or no substance is there. A pretty face; a well-sculpted torso, but alas, nothing sustaining beyond the physical. Similarly, art can sometimes be exciting in an instant and give away to disappointment in the next; no depth to the pretty arrangement of colours or the beautiful form. At this moment, I’m thinking of different colours of paint thrown at a canvas. Regardless of the outcome, the beauty of a formal analysis is that without knowledge of the background of the work – the artist’s biography, the social context out of which the work emerged, etc – it is possible to have a meaningful interaction with the work in question. Therefore, please don’t be overwhelmed by visual art.

“It should be remembered that a picture — before being a warhorse, a nude, or an anecdote of some sort — is essentially a flat surface covered with colours assembled in a certain order.”

These are the often-quoted words of French artist Maurice Denis (1870-1943) when he was just 20 years old. What insight for one so young! In fact, Denis’s words were a reaction to imitation in art. For Denis, in 1890, the pleasure in the painting was not to be found in the subject and content and how well these were painted but in the visual qualities of the elements and principles. While his focus on the formal qualities did not persist throughout his career, formalism as a way of looking at art and approaching the making of art was born.

Formalists recognise that not all viewers/audiences of a work of art will read the symbolism in a work the same way. Hence, formalists recognise the reality of diversity within audiences. Thus, individual viewers are unlikely to all arrive at the same meanings whether religious, political, or of another category. Formalists also recognise that audiences bring their past experiences and their lived realities to the viewing of work. These experiences and realities may be tempered by age, sex, gender, social class, and education, among others.

It should be noted that the relationship the audience develops with the work and will not be burdened by narrative – the story the work tells. Looking at art through the lens of a formalist also allows one to bring an understanding of media – the materials used to make the art – techniques applicable to different media, styles, and movements in art.

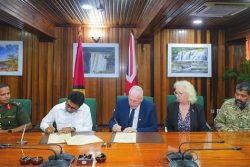

As a lover of art, visa-free travel to the United Kingdom is welcome news! But as lovely as meandering the halls of the UK’s National Gallery of Art is, so too is exploring the gems on the walls of our own National Gallery of Art, Castellani House. One can never be sure when one will come face-to-face with the spirits of an ‘Old House’ painted in acrylic, a reposed watamama carved in wood, the rich textures of an impasto painting, or the subtleties of glazes of colours layered upon each other. One can never be sure whether one’s enthusiasm for artistic brilliance will be heightened by the serene beauty of lotus lilies in bloom, conspiratorial gaffs over a fence, or anxious night skies illuminated by black moons. Therefore, now that our National Gallery of Art is open again (since late September 2022) go and take a walk and see what excites you, if you have not visited that house of treasures as yet.

As I write these articles, I am never sure if I am connecting with readers in the ways I hope. Art is not a straightforward thing! I am aware that a lot is not right for art in Guyana and that knowledge propels me forward. Nonetheless, I love knowing artist’s stories and hope you will delight in them as much as I do. Next week, I will begin to share impromptu conversations with Dudley Charles, artist of the ‘Old House’ series that is so relished by many a lover of the art of Guyana.

Akima McPherson is a multimedia artist, art historian, and educator.