Introduction

For better or worse, Guyana has hitched its future with the American oil giant ExxonMobil. No longer seeing its duty to exert on the company and the industry adequate regulation and strict supervision, the Government now regards Exxon Exploration and Guyana Production Limited (EEPGL) – the Bermuda company whose branch in Guyana heads the Stabroek Block production consortium – as a partner to be defended and protected. Despite the PPP/C’s Manifesto commitment to better contract administration and renegotiation, the Government is now so accommodating to the oil companies that the country’s already weak laws are completely ineffective. Indeed, the failure to increase the 2023 Budget allocation to the Environmental Protection Agency, its slothfulness on updating the 1986 laws or establishing an independent Petroleum Commission seem motivated by a desire for control and secrecy in the Government – industry relationship.

The Government cannot be unaware that less than one week before the Budget, the London Guardian reported that as far back as “at least the 1970s”, Exxon, EEPGL’s parent, knew of the dangers of global heating but spent the next several decades “publicly rubbishing such science in order to protect its core business”.

Culture runs deep. Exxon’s subsidiary in Guyana has not conducted its operations here with any greater rectitude, strongarming the APNU+AFC Coalition Government into granting it a second Petroleum Agreement in 2016 in which it cravenly claimed, on its own and its co-venturers’ behalf, around US$100 million more in pre-contract costs than their own audited financial statements reflected.

Mindful of the global trend to abandon fossil fuels, Guyana’s situation mirrors the experience of Ecuador, another developing country, whose President Guillermo Lasso said last year that “the time has come to extract every last drop of benefit from our oil, so that it can serve the poorest while respecting the environment”. Lamenting the loss of pristine environmental resources, one of that country’s ecologists postulated the rule that “when it comes to economic matters, nature always loses”.

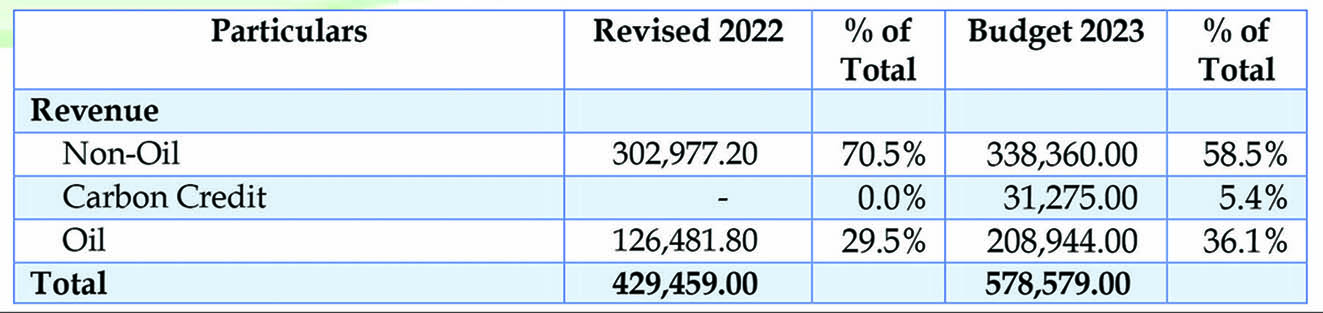

As the Table below shows, in 2022, the proceeds of direct flows from oil contributed 29 % of the revenues in 2022. In 2023, that share is expected to increase to 36%. In a matter of three years, Guyana’s budget is now oil dependent. Following the President’s pledge towards acceleration rather than consolidation and review, diversification of the economy becomes more challenging.

Revenue Analysis

Source: National Estimates Appendix A (GY$ Millions)

Source: National Estimates Appendix A (GY$ Millions)

The Budget was presented on January 16, ten days earlier than in 2022. This is still unacceptable. As the law stands, until there is an approved Budget, spending by various Budget agencies is limited to one-twelfth of the expenditure in the preceding year. Approval while certain, is unlikely to happen before the end of this month.

Ram & McRae therefore advocates an amendment to the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act making it mandatory that the budget be presented sometime in October or November of the preceding year.

Inevitably, it was the largest Guyana budget ever, with the generous helping of funds from the Natural Resources Fund and some $31,275 Mn. from the sale of carbon credits. Correspondingly, it was also the largest budget deficit ever. There were no Corporation Tax measures while the only income tax measure was an increase in the personal allowance. VAT on the sale of residential properties and all-electric vehicles was removed along with some excise taxes.

Erroneously in our view, the Minister estimated that these measures would cost some $50 Bn, some of which must be clearly hypothetical.

One feature of this Administration has been its increasing reliance on Cash Grants as a poverty cushioning measure. With the Government’s stubborn refusal to raise the national minimum wage, it seems that for some long time into the future, cash grants will be the principal tool of poverty reduction. That the world’s fastest growing economy is being sustained by one of the lowest minimum wages in the world sits uncomfortably with each other.

One measure of concern on the expenditure side is how reported underspending in the Mid-year Report, sometimes with calls for supplementary appropriations, is eliminated by the end of the year. Helpfully, the Speech is accompanied by an Appendix of Selected Socio-economic Indicators but to which there is no direct reference in the Speech. Some of these indicators do not appear to support the positive outcomes identified not only in 2023 but in previous Speeches as well.

Ram & McRae welcomes the return to growth in the rice sector and the stability of the exchange of the Guyana Dollar.