In today’s column I expand on the reasoning I gave last week as to why I am urging that, there is no sound economic theorizing in calls for Guyana to establish a state-owned oil refinery to process (and thereby add value) to its crude oil production, at this stage of development of the country’s emerging oil and gas sector. As I have stressed last week, such calls emanate from an autarkic economic paradigm.

This paradigm advances the thesis that, “Guyana’s path for its autonomous sustainable development requires the State (Government of Guyana, GoG), to pursue a line of march that ensures, Guyana produces all it can produce”. To be able to do so, it must therefore constrain (legally, administratively, and fiscally) “foreign, ownership, control of decision-making, and management of its evolving oil and gas sector”.

Further, I had in last week’s column also indicated that the developmental limitations and weaknesses of autarkic development, given that, particularly for Guyana, the reality for Guyana is, the country is far too small, and therefore not ever likely to become a significant consumer of all or even most of its potential processed crude oil production.

More importantly for present purposes, in that column, I had further adverted to the truism: “no two oil refineries are the same”. This truism is clearly evident in the data showing the number, output sizes and distribution of oil refineries, worldwide. Indeed, in large measure this truism applies not only to the various sizes of refineries, worldwide but the variation also in oil refinery capabilities. This phenomenon is the main focus of today’s column.

Oil Refinery Capability

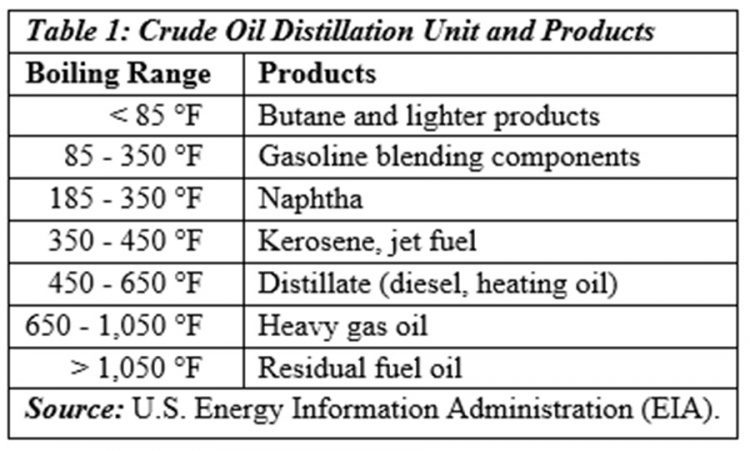

As I had sought to make clear in my 2019 columns, in its essence oil refinery capability refers to the petroleum products which it can produce from crude oil input. The basic requirement of all oil refineries is a distillation column; which typically, separates the crude oil into different petroleum products, based essentially on their differing boiling points. The distillation column is combined with secondary processing units. The information in Table 1 shows the varying boiling points for a sample of crude oil and its product derivatives.

In my earlier columns I had also introduced readers to the standard industry-wide indicator of the level of capability of any oil refinery, and therefore the rationale behind the truism: “no two oil refineries are the same”.

Empirics: Nelson Complexity Index

Industry glossaries reveal that the Nelson Complexity Index is the standard measure of oil refining capability and complexity. It does so through the level of secondary conversion capacity there is in the refinery; after considering the cost of each major type of refinery equipment. For the Index, the distillation column is given a value of 1 and the other units in the refinery are then assigned values on the basis of their conversion capability and their cost relative to the distillation column, which is valued at 1. The larger therefore, is the Nelson Index, the more complex is the refinery. And, the more complex is the refinery; the more capable it is of producing higher valued products. And, correspondingly, the costlier they are to build and maintain.

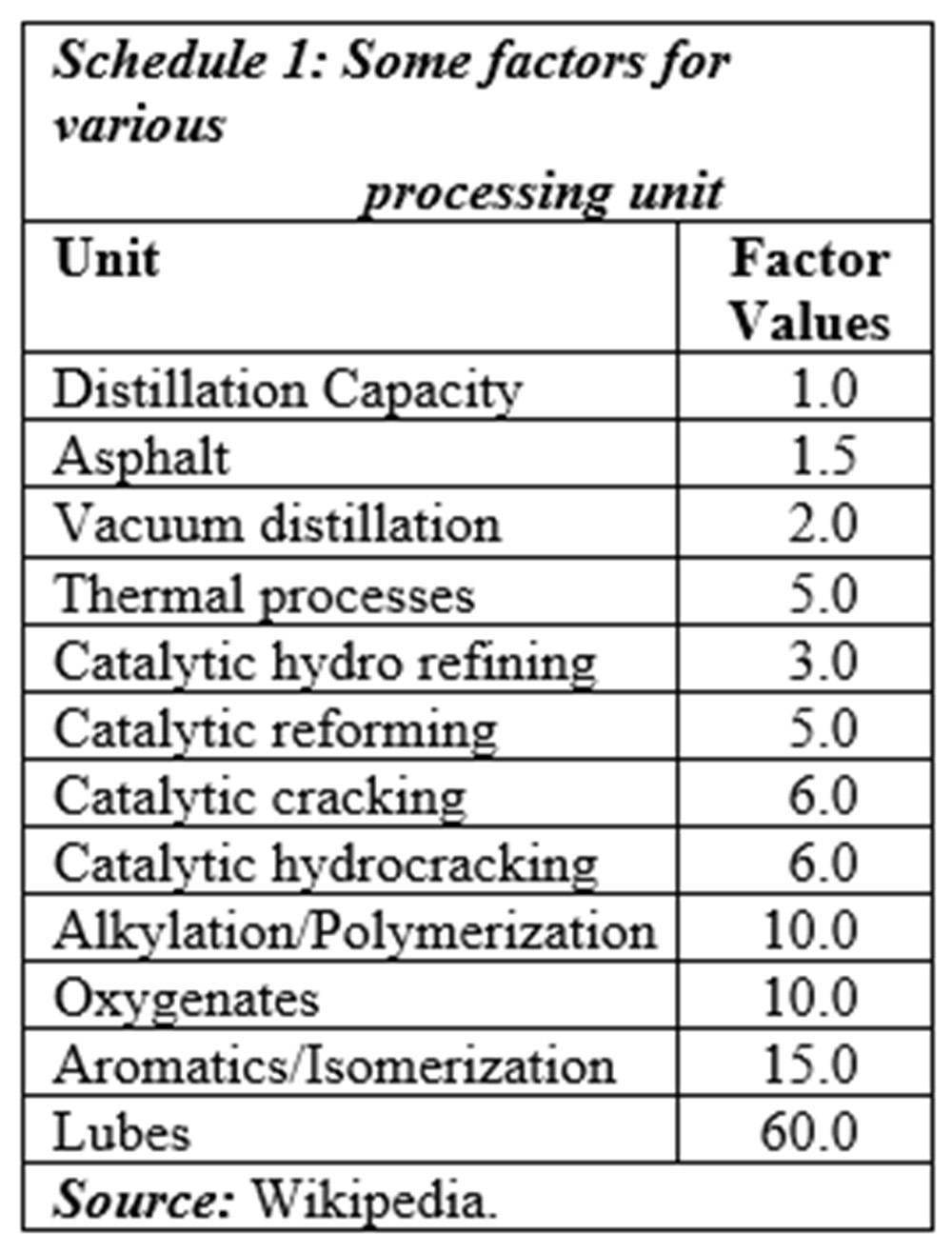

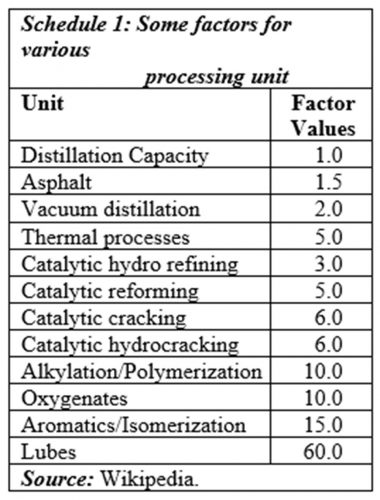

Typical complexity factors are shown in Schedule 1. Two decades ago, back in the 2000s, the global value of this Index was 5.9

Schedule 1 provides a guide as to the “factors” allotted to the various levels of capability in a typical refinery. I believe it is worth noting that the Nelson Complexity Index, is more carefully described as an effort to quantify the sophistication (technological and otherwise) of a refinery, along with its capital intensity. Complexity, as used in the industry classifies refineries hierarchically, and estimates refinery construction costs.

Conclusion

Next week’s column re-visits my several contributions over the years evaluating publicized efforts by the Authorities in considering the feasibility of building a state-run or JV oil refinery based on a value added operation using Guyana crude.