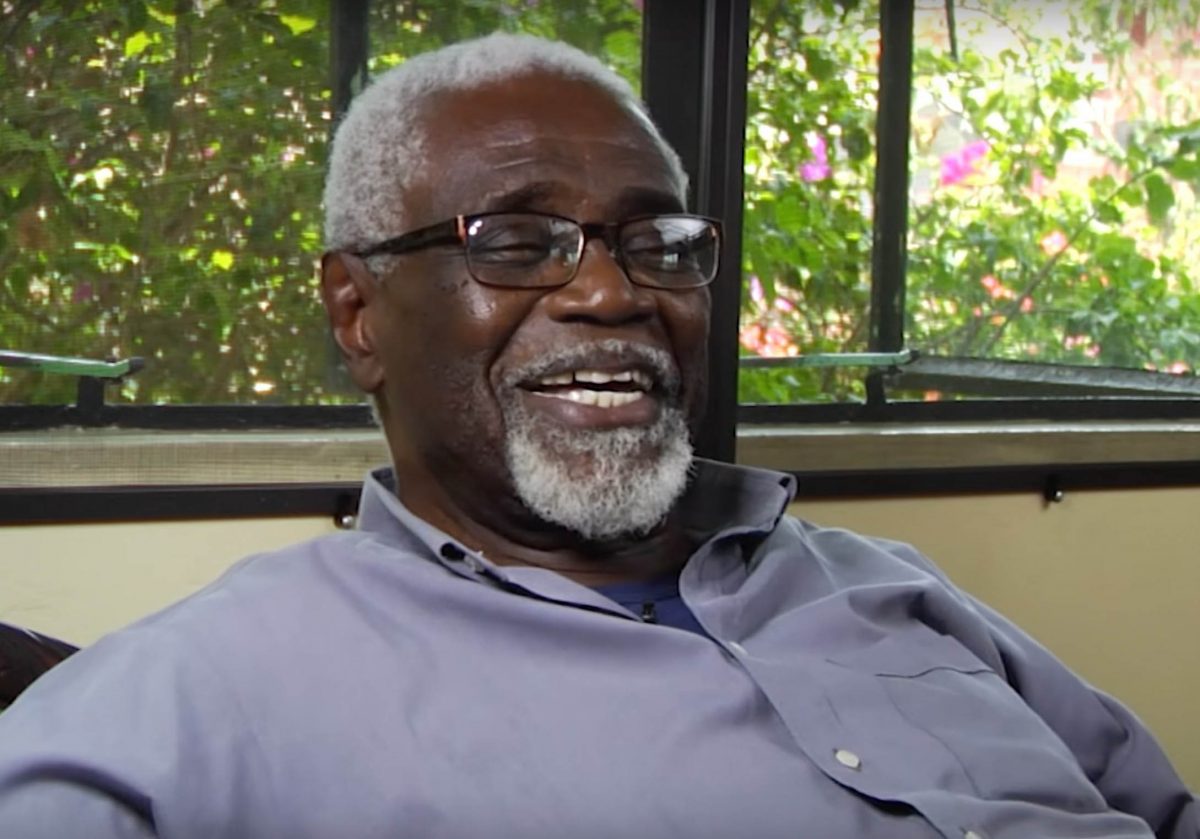

(20 February 1942-29 January 2023)

By Richard Drayton

Richard Drayton, born in Guyana and also a citizen of Barbados, is a Professor of Imperial and Global History at King’s College London

“Well he lost his memory/

what a thing to stand up and see/

how it is he forget to remember/

what it is he forget remembering”

So the Mighty Spoiler, calypso surrealist, conjectured in “Lost Memories” (1960) how repression could be forgotten. Gordon Rohlehr, literary critic, essayist, historian of Calypso and Carnival, who died on January 29, shared this conjecture. He was a warrior against amnesia, fighting battles to preserve and extend a continent of the Caribbean self which like his native Guyana was always at risk of slipping under the water. With pen, tape recorder, files and archives, and his own extraordinary memory, he read and wrote and prophesied against all the kinds of unconsciousness, all the carelessness about the past, the neglect of ancestral inheritance and ignorance about ourselves.

Rohlehr understood that psychic and intellectual self-neglect as the partner of our region’s history of violence and of what Cesaire called “thingification”. Like Lamming, his special enemy was that alienation between that minority produced by Walcott’s “sound colonial education”— people like himself, who he joked in later life, was just another “Afro-Saxon” – those caught in the paradox of an articulacy intended to fit them for service to distant strangers, and the creative power and intelligence of the unlettered masses. C.L.R. James, Rohlehr said, “was convinced that the people were not stupid”, and Rohlehr’s entire intellectual journey was founded on this doctrine.

Daniel Frederick Gordon “Bosco” Rohlehr was born in British Guiana in February 1942. He was the third of seven children of Herman, Superintendent of the Government Reform School, and Iris, a Schoolteacher. Growing up with roots in Berbice, where the Dutch ancestor whose name he bore had managed Plantation Albion, he was formed by the rivers, bush and cane fields of Essequibo. He was formed equally by the presence of Africa in Guyana’s culture, by mystical dreams which travelled through him from early childhood and sculpted that deep inner life which would be his refuge and resource. Musings, mazes, margins: a memoir (2020), his last book, is record of a lifetime of these dreams, in tension with his will to self-consciousness. He was marked too by political trauma, having entered Queen’s College in that fateful rainy season of 1953 when the Constitution was suspended by the British. It was, he wrote later, the first of many experiences of political catastrophe which marked his life, which he worked and dreamed, in spite of it all, from the crisis of 1961-4 which left wounds on his homeland which never healed, to the murder of Rodney and the destruction of the Grenada Revolution, to the larger sadness of the unfulfilled promise of political independence.

He was part of that brilliant early 1940s generation of Walter Rodney, Andaiye, Ewart Thomas, Rupert Roopnaraine, Marilyne Trotz, Alvin Thompson and Winston McGowan. His teachers at QC included the extraordinary polymath N. E. Cameron and Richard Allsopp (who later would compile the legendary Dictionary), but like Rodney and Thompson and McGowan, he was particularly influenced by the history teacher Bobby Moore, then beginning his work on the Berbice Slave Rebellion. When he left on a scholarship to the University of the West Indies at Mona in 1961, it was to study History. But he changed to English, perhaps recognising that his calling was as a historian of the spirit. Mona at this time was the crossroads of talented people from every corner of the region, and its impact on Rohlehr was to turn him from a Guyanese to a West Indian. It was as a West Indian that he left in 1964 for Birmingham, choosing Joseph Conrad, who he read as a fellow colonial, as the subject of his doctoral thesis.

In Britain, he became involved with the Caribbean Artists Movement, forming an important, indeed life changing, relationship with Edward Kamau Brathwaite, the Barbadian poet, historian, literary critic, and himself a formidable archivist of letters and music. Kamau’s vital role was to insist that Caribbean artists and intellectuals had to dig down to recover the African inheritance, what Herskovits had called ‘retentions’, which had been buried by generations of colonial contempt and education. Brathwaite urged a new generation to search in mento and calypso for keys to a new Caribbean aesthetic and an authentic post-colonial self. Under his influence, Rohlehr wrote his 1967 essay on the language of the Mighty Sparrow, which set him on the road he would pursue for the rest of his life.

Gordon took Kamau’s programme home, as he came to a Lectureship at the new St Augustine campus of UWI, where he would work for the next 40 years. He was caught up in the ferment of 1968, becoming an important contributor to Lloyd Best’s *Tapia* newspaper, and a keen witness of the Black Power revolt of 1970. From Best he took the view that Caribbean civilisation had to be built from a reach inside, that we were enough, and we could make abundant our parcel of earth, like the peasant builders of the ‘tapia’ houses. It was in *Tapia*, in December 1970, that he published one of his most famous essays: “History as Absurdity”, at once a penetrating review of the weaknesses of Prime Minister Eric Williams’s *From Columbus to Castro* of that year, and a Fanonian analysis of “the cultural predicament of the Afro-Saxon colonial”, caught between rebellion and the yearning for the approval of the English. The essay, published at a time when Williams had shown his ability to deprive non-Trinidadian scholars of work permits, showed that Daniel-in-the-lion’s den fearlessness that would erupt at many moments, not least in ‘Trophy and Catastrophe’, his 1987 Guyana Prize Lecture, in which he denounced the murder of Rodney in front of the leaders of the PNC.

Rohlehr began around 1970 a decade of work on Kamau’s poetry which culminated in *Pathfinder: Black Awakening in the Arrivants of Edward Kamau Brathwaite*(1981). *Pathfinder* is a quite unique combination of close reading and meticulous research into literature’s philosophical, musical, historical and ethnographic underpinnings, arguably the most important critical work ever done on a Caribbean poet. But it was beyond this, Rohlehr’s main statement on Caribbean civilisation, a work of extraordinary erudition. ‘Veins of Beginning’ its opening section, explores the ‘great and little’ European, American and African traditions within which Brathwaite was negotiating his (and our) voice, and the book situates with grace and fluency the twentieth-century literary inheritance of the region in three languages. Commercial presses were wary of a work of such complexity and ambition, but Rohlehr, in the spirit of an earlier generation of Caribbean intellectual like J.J. Thomas or N.E Cameron, simply published it himself.

But *Pathfinders* was also a spiritual, even an evangelical work. To read it, and I read it at 18, spending my 6th form prize (won for Chemistry and Biology!) to buy this mysterious book, was to learn how to journey into one’s own Blackness, all the spiritual and imaginative treasure which is part of our African inheritance. At its foundation was that belief which Rohlehr shared with Brathwaite, that the melting pot version of the idea of Creolization was a dangerous renegotiation of the colonial contempt for and neglect of Africa. He rejected the political ‘out of many one people’ demand which sought to silence and foreclose our long postponed encounter with the unique and distinct experiences of suffering and survival of the Amerindian, African and Indian, and even Chinese and Portuguese, cultures of the Caribbean majorities. He saw both in Guyana and Trinidad how this doctrine could be ruthlessly deployed, in turn, by both African and Indian ethno-political oligarchies to deny the sensitivities of others and exclude them from full civic participation. He was wary of what he called “the mulatto aesthetic” in our literature and philosophy, that prizing of mixture and hybridity which presumed the right destiny of our civilisation to be a kind of ‘browning’ in which the European ‘one drop’ was the special sauce. He offered the radical view that Caribbean Studies had to begin with the long and hard work of understanding the specific and distinct cultural worlds of Guyana, Jamaica, Barbados, and Trinidad, and the distinct ethno-cultural worlds within them, rather than forcing a quasi-imperial ‘nationalist’ consensus upon them.

Putting his bucket down where he lived, he turned his research energies to Calypso, seeking to treat that popular oral literature of Trinidad, forged across the Twentieth century, with the same scholarly care that he addressed texts. Conducting a long programme of work in the archives and libraries of Trinidad, in combination with ethnographic fieldwork among the calypsonians, he began what would lead to what is recognised as his masterwork, again self-published, *Calypso and Society in Pre-Independence Trinidad* (1990). Much as Walter Rodney refused the ivory tower, and went to the hills and slums of Jamaica to learn from the poor, so Rohlehr grounded in the pan yards and calypso tents of Port of Spain, and had the privilege of meeting the surviving kaiso men of the ‘golden age’ of the 1930s and 40s. He formed friendships with Sparrow and Melody, Rose and Francine, Stalin and especially Shadow, with whom he felt a particular spiritual affinity. As the calypsonian Short Pants praised and lamented at the memorial service on February 4:

“what makes it very hard

Is he took Kaiso from the barrack yard

brought it to the University

And gave Kaiso respectability”

Rohlehr showed how the calypsonian had been the tribune of the people, recovering jewels such as the first known explicitly political calypso, the ‘re minor’ lament of ‘Chinee Patrick Jones’ in 1920:

“Class legislation is the order of this land

We are ruled with an iron hand/

Class legislation is the order of this land

We are ruled with an iron hand/

Britain boasts of equality/

Brotherly Love and Fraternity/

But British colonists have been ruled/

In perpetual misery/

in this colony”

Jones had been censored, and a central part of Rohlehr’s monumental work was his study of censorship, and of how the calypsonians sought to find ways of saying what needed to be said in spite of it. He formed an argument, which has close affinities to Edouard Glissant’s idea of ‘forced poetics’, that calypso derived much of its literary and rhetorical complexity from that task of evasion, from the burden of finding ways to speak to and for the people in a context of repression. This Rohlehr saw as the key to our whole civilisation, a culture which struggled against external powers which then and now sought to reduce and keep us as brute workers and consumers, who imported words and dreams with flour and iPhones, living in amnesiac inarticulacy.

Rohlehr was a gifted stylist with a great sense of humour, fond like Derek Walcott of calypso puns, joking in letters to friends about the “Aculty of Farts”, with lecture and essay titles like “Trophy and Catastrophe”, and dark jokes about “the wrack of Georgetown, the ruin of Port of Spain”. At my mother’s dinner table he told me, with a huge laugh, his favourite calypso couplet:

‘This English language/

It sweet like a corn beef sandwich’/

He could be silly, and he was always light and self-ironising, conscious of, and at peace with, his own absurdity, his cult of the word in a society for which books were more gestured at than read. But he was at the same time deeply serious, unafraid of a lonely act of witness. The depth of reading and intellectual and moral urgencies may be recovered from his collections of essays, including My Strangled City (1991), The Shape of that Hurt (1992), A Scuffling of Islands (2004), and Perfected Fables (2019).

Gordon enjoyed a long and happy marriage with Dr. Betty Ann Rohlehr, out of which came two children, Donna and Deke. Deke in his tribute spoke for us when he said he had never seen his father say anything unkind. Gordon is remembered by all who knew him for his deep gentleness and caring, his capacity to take a personal interest in those who crossed his path. He was a powerful teacher, his lectures and classes leaving a deep mark on many generations of students.

A great and unique Guyanese and Caribbean spirit has left us, but this heroic Bookman has left us a body of work, and a personal example, which represents one of the finest fruits of our experiment of independence.