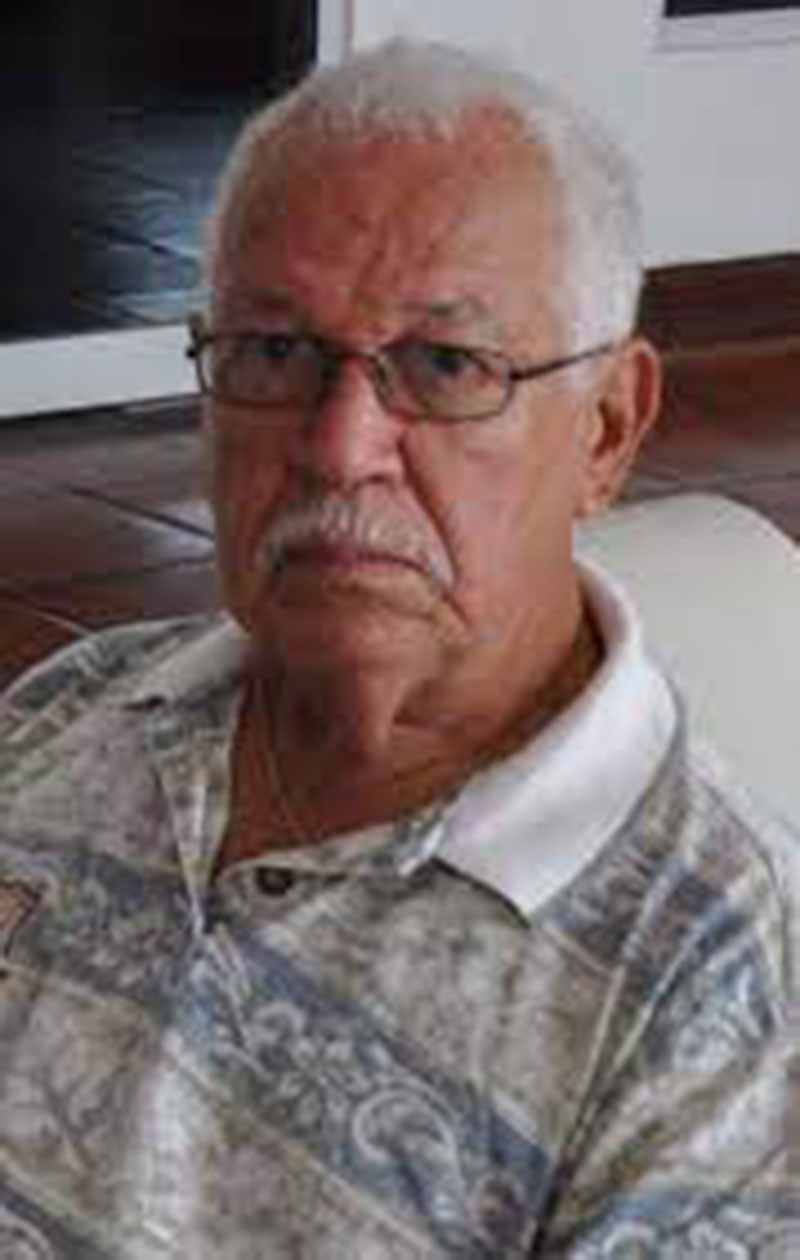

(Clem Seecharan is a cricket Historian and author of Hand-in-Hand History of Cricket in Guyana, two volumes of which have been published. He is writing the third. This tribute has been prepared for the “Night of Recognition” for Joseph ‘Reds’ Perreira which is to be held at the GCC on March 8th.)

This year marks the 165th anniversary of the founding of the Georgetown Cricket Club (GCC), and 138 years since it relocated from the Parade Ground to Bourda. You have hosted many memorable matches (including the first Test ever won by the West Indies, in February 1930). You have sponsored numerous events in appreciation of people of high achievement in our noble game. But it gives me ‘abounding joy’ that you are tonight honouring Joseph ‘Reds’ Perreira, one of the most accomplished radio commentators in the history of cricket, nearly 52 years since he first commentated on a Test match. It is entirely appropriate, therefore, that this celebration of Reds’s life is taking place at Bourda, for this was the venue of that match, West Indies v. India, in March 1971.

When Reds retired he had covered 152 Tests in every cricketing country save Bangladesh, over 200 ODIs, five World Cups and numerous first-class matches, the first being in October 1961, BG v. Trinidad at Rose Hall. In the process, he has mastered the art in the company of, and unfazed by, its most eminent practitioners in the history of cricket: John Arlott, Alan McGilvray, Brian Johnston, Dicky Rutnagur and his great friend and mentor, Tony Cozier. Reds belongs to this illustrious company by virtue of his capacity to paint an instant picture for radio listeners thousands of miles away. Reds’s style, his interpretation of play, was uncluttered by tedious embroidery on matters beyond the boundary. He sought to render, with precision, what was taking place within the boundary, so that you could feel as if you were there, at Bourda, Lord’s, the MCG or at Eden Gardens, Calcutta. Reds, of course, conveyed those images to us, for several decades, from all these historic grounds and many more.

But there’s a hinterland to Reds’s attainments, beyond the simple matter of mastering a difficult and extremely rare art. Born in the remote district of Pomeroon in Essequibo, nearly 84 years ago, Reds stammered severely until he was about 20. And it got no better, away from the security of his natural habitat, after his family moved to Georgetown in 1945, when he was six. In the unconscionable environment of his boyhood in the capital, Reds survived from day-to-day, learning to let the taunts and provocations slide away. But it taught him to swim against the tide, a skill he had absorbed practically from birth, on the mercurial Pomeroon River. So one could readily have comprehended if Reds had decided to become an umpire, a scorer or even aspire to open the batting for the West Indies, accompanying Conrad Hunte. But Reds was irrepressibly predisposed to going against the grain: the stammer had to be conquered. He would endeavour to extinguish it on its own turf − by narrating imaginary cricketing episodes; rehearsing continually at being a cricket commentator. Moreover, he had the resolve and the character to make that a reality, and to reach for the stars, in this unimaginably challenging vocation with nowhere to hide.

He did reach the stars. But it was as if some higher force had designs on restraining Reds, forcing him back to earth. On New Year’s Day 1996, while touring Australia with the West Indies, he suffered a stroke. Lesser mortals would have succumbed! Reds ain’t no lesser mortal! As he tells it: ‘It was not as hard as overcoming stammering. That had infused me with the confidence that I could fight any adversity in life’.

What Ian McDonald observes with respect to Reds’s tenacity of purpose, an implacable pursuit of excellence, should make Reds’s challenges and response eminently relevant to all Guyanese (all West Indians). His is an exemplary life marked by continuity of focus − inspired by the will never to be a victim, but to pioneer paths that others deem out of bounds. Ian was responding to Reds’s autobiography of 2010, Living my Dreams: ‘Reds’s life story is a remarkable Caribbean tale of difficult beginnings, adversity and long odds overcome, opportunities grasped, challenges met and dreams fulfilled – altogether a fascinating personal odyssey’.

Shortly after the publication of Reds’s book, Sir Ron Sanders did a review that was published throughout the region. He conveys the essence of what made Reds the superb commentator and sports administrator he was − a true West Indian who has set a benchmark of distinction − and in the process inspiring many he has touched with self-pride and enterprise:

The book’s importance is that it shows that there is no obstacle to realising dreams and achieving ambition if one has self-belief, determination and unrelenting capacity for hard work. Every obstacle can be overcome…

Reds is perhaps better known as a cricket commentator, but he is much more besides. He has also been a successful sports administrator in Guyana and for the seven islands that form the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), and there is no sport in the region that his life has not touched in some measure…

Sir Ron adds that while, initially, some in the OECS had reservations regarding assigning such an important post to a Guyanese, yet by his professionalism and his empathy, Reds was soon able to reverse such misgivings: ‘After 26 years of sterling and unselfish service to almost every sport in the OECS, few now remember that Reds was born in Guyana. In a note in the book, Lester Bird [the former Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda] said: “You set a great example that will be difficult to emulate”’.

Reds speaks of the seminal influence of the gifted Australian commentators, whom he listened to on radio all night, during the memorable West Indies tour of Australia in 1960-61 (led by Frank Worrell): Johnnie Moyes, Michael Charlton and Alan McGilvray. But it is primarily his fellow masterful West Indian, Tony Cozier, to whom Reds attributes his own ascendancy: ‘I was very lucky to work with Tony Cozier for over 40 years and his standard pushed me to work harder to maintain the level that he had set. It was not just going along for the ride. It really made me a better commentator to work shoulder to shoulder with Tony Cozier’.

I became a good friend of Tony Cozier during the last ten years of his life, and most summers when he was in London, we used to meet for lunch at a West Indian restaurant in Camden Town. Tony would regale me with wonderful tales (some unrepeatable) from his amazingly rich life, indelible in the archive of his mind. He told me that he first went on air in a Test match in March 1965, in Jamaica, with Alan McGilvray, who put him at ease immediately. Tony said that the accomplished Australian had the ability to tell you precisely what was happening on the field, with no frills or diversions that made the cricket secondary to the chat. Tony respected John Arlott, too, but he said no one could emulate the uniquely poetic old master. However, one could adopt McGilvray’s approach, as Tony did; and he also pointed out to me that Reds Perreira, too, was guided by the maxim of the great Australian veteran − the instinct for narrating precisely what was happening on the field, thereby enabling you to feel engaged in the process. A spectator relishing the spectacle!

Ian McDonald recalls that he came upon a sign many years ago, in Barbados, that read: ‘Listen to Cozier − Tinnin don’t lie’! It took him a while to get it. It refers to the biscuit tin or a piece of corrugated zinc used by boys playing random cricket everywhere in Barbados. The distinct, unmistakable sound when the ball hit the improvised wicket, left no doubt that the batsman was bowled. No argument! Tinnin don’t lie!

I cannot resist appropriating this pithy refrain for Reds’s proficiency on air. It encapsulates his own astounding rise to the pinnacle of his calling, from adversity to mastery as a radio commentator for over five decades. ‘Listen to Reds – Tinnin don’t lie’! That boy from Pomeroon always tells it clearly, concisely, correctly, as it happens.