When was the last time two films in a major Oscar category featured varying interpretations of a single character? The renowned lying puppet “Pinocchio” appears as a figure in both of the current frontrunners for Best Animated Feature at this year’s ceremony, due later in March.

When was the last time two films in a major Oscar category featured varying interpretations of a single character? The renowned lying puppet “Pinocchio” appears as a figure in both of the current frontrunners for Best Animated Feature at this year’s ceremony, due later in March.

DreamWorks’ “Puss in Boots: The Last Wish”, a sequel to the 2011 film and the sixth entry in the “Shrek” franchise, briefly features the wooden would-be boy as a character. “Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio” is a new adaptation of the story about that same wooden boy. The two films are joined by more than the puppet, though. Both weave tales of magic and fantasy into somewhat sombre real-world allegories about death and life and family. And both films, despite their occasionally inspired engagements with magic as restrictive and full of possibility, feel more inelegant and overfamiliar than inspired or striking in their invocation of familiar characters and stories.

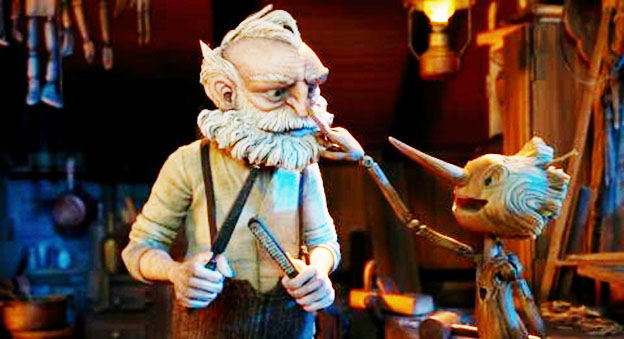

It’s difficult to say whether the wordy title “Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio” announces the Netflix release as something lofty or cumbersome. Unfortunately for del Toro, his film has the misfortune of being the third adaptation of Pinocchio in the last three years. I’m not sure why the story, originally written by Carlo Collodi of Tuscany in 1883 of the puppet who becomes a real-boy and goes through a series of grotesque mishaps, has been enjoying a mini-revival. However, it is easy to see why del Toro, who has always been fascinated by whimsy, children, morality and magic, is fascinated by it. del Toro’s first animated film, the stop-motion designs in “Pinocchio” are influenced by the 2002 illustrations Gris Grimly drew for a new edition of the book. The grotesque fabulations give del Toro’s meticulous attention to detail a chance to unfurl.

It’s difficult to say whether the wordy title “Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio” announces the Netflix release as something lofty or cumbersome. Unfortunately for del Toro, his film has the misfortune of being the third adaptation of Pinocchio in the last three years. I’m not sure why the story, originally written by Carlo Collodi of Tuscany in 1883 of the puppet who becomes a real-boy and goes through a series of grotesque mishaps, has been enjoying a mini-revival. However, it is easy to see why del Toro, who has always been fascinated by whimsy, children, morality and magic, is fascinated by it. del Toro’s first animated film, the stop-motion designs in “Pinocchio” are influenced by the 2002 illustrations Gris Grimly drew for a new edition of the book. The grotesque fabulations give del Toro’s meticulous attention to detail a chance to unfurl.

And so, his “Pinocchio” is distinguished by an almost surreal aesthetic language that emphasises the unreality of the wooden boy and the Italian world he inhabits. You feel you can almost imagine the roughness of the wood in the way the animation is realised. del Toro shares directing credits with Mark Gustafson and writing credits with Matthew Robbins in this adaptation that transposes the story to early 20th century fascist Italy. The story, which was already didactic in its moral messaging, becomes even more-so and not necessarily for the better. Geppetto, Pinocchio’s maker, loses his young son in World War I when a plane drops a bomb on a church. Geppetto is still grieving twenty years later, on the cusp of World War II. He cuts down a pine tree in a fit of pique and carves a boy-like puppet from it who is magically made sentient the next day. The initial misadventures as Pinocchio tries and tries, and fails and fails, to be a good boy are heightened when he is enlisted to fight for Italy in the war. Because he is not real, Pinocchio cannot die, and so becomes a model of a potential soldier. Able to die and die and die for his country.

Pinocchio has always had an epic edge to its story that meanders as a kind of odyssey, and in this new iteration rich with religious imagery and critique of fascism, for all the specificity of its spectacle, I found “Pinocchio” to be too often convoluted in its realisation of the story. And I’m no Del Toro sceptic. I consider his work in “The Shape of Water” to be one of the most elegant pieces of film in the last decade that manage to achieve a literary wistfulness that is very often resisted in contemporary work. But the attempts at elegance in “Pinocchio” feel more tedious than whimsical. The story is propelled by an allegory within an allegory, buoyed by some indistinct and limp musical numbers, and it feels inchoate and cumbersome. Certainly, its aesthetic commitment is precise but I’m not quite sure what depth lies in that precision. David Bradley is a committed Geppetto, and Tilda Swinton injects what she can into the magical beings she voices but the voice-work beyond that is mostly too indistinct to register. Some moments, a paltry few, register and it’s at least too sincere to completely dismiss but also when sincerity is so effortfully deployed (truly, so laboured beat after beat after added beat) it soon becomes a listless affair.

“Puss in Boots: The Last Wish” is, at least, less listless an affair but it is a film that also feels neutered in its engagement with the familiar. In this sequel, we meet an older but not wiser Puss (again voiced by Antonio Banderas) who is on his ninth life when Death personified comes calling for him. A quest lies ahead. News reaches him of a legendary wishing star which promises a chance to restore his previously used eight lives. But the quest comes with foils. In the form of his former lover Kitty Softpaws (Salma Hayek), Goldilocks (Florence Pugh) and her foster family of the three-bears and “Big” Jack Horner (John Mulaney). The competing teams, including a new dog-sidekick for Puss and the looming figure of Death, venture into an enchanted forest in their quest where characters learn about themselves and each other and evil is defeated, naturally. It all comes across as a bit ambivalent.

There’s a clever hook here: various characters, some familiar fairytale ones and some new, each set out on a perilous journey for a fleeting magic wish but the plotting here is only a facsimile of Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s intertwining of fairy tales in their Broadway hit “Into the Woods” . Each player’s journey is enchanted to fit them in “The Last Wish”. But then what? In plotting, Paul Fisher and Tommy Swerdlow’s screenplay (with additional story credits for Swerdlow and Tom Wheeler) is a bit too self-satisfied with its arcs which never feel daring or thoughtful enough. Joel Crawford’s direction is occasionally striking with some briefly thrilling sequences, but it often feels like a familiar retread in cruise control. The three major “wishes” we end up with at the film’s end feel too easy to register and the climactic standoff with a sleight-of-hand that closes the film is too easily resolved to build momentum. Maybe I am slightly ungenerous for a film nominally for children, but it all feels so effortful.

There is enough commitment in the engaging, if inconsistent, visual thrills but I’m not fond of Banderas or Hayek giving into their most obvious instincts in this franchise, so there’s nothing really riveting in the voicework, including Olivia Colman as Mama Bear doing her best Emma Thompson that only reminds me of “Brave” (a much better film about magic and family and morals). There’s an almost officious tone to its pleasant and precocious quips, but must it all feel so insubstantial?

Between this and “Pinocchio”, I’m wondering if I might be missing something with recently celebrated animation but it seems a shame that a medium of so much possibility might come down to these middling entries when the Oscars are handed out later this month.

“Pinocchio” is currently streaming on Netflix, and “Puss in Boots” will move to Netflix later in the year after streaming-for-pay on Peacock for four months.