By Nikita Blair

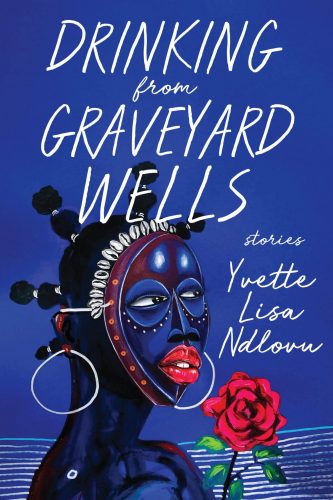

March is Women’s History Month, in which we celebrate women’s contributions to history, culture and society. This year’s theme is “Celebrating Women Who Tell Our Stories”, acknowledging the women—both past and present—who have been active in all forms of media and storytelling. This year, my readings have taken me all the way to Zimbabwe with a collection of speculative short fiction that mostly centres around women and their experiences living in a patriarchal society while they navigate capitalism, immigration, resource and worker exploitation and womanhood. This book is Drinking From Graveyard Wells by Yvette Lisa Ndlovu.

Drinking From Graveyard Wells contains 13 stories and a series of 12 interconnected microstories in which Ndlovu uses science fiction, afro-surrealism, and absurdist fiction to examine these themes in chilling, genre-bending and heart-breaking ways that are as fantastical as they are true. Yet, amid the horror of this collection, there are elements of hope as the characters find ways to live in systems that often disenfranchise and disadvantage them. While I enjoyed many of the stories in this collection, I only have the space and time to review a few. These are my favourites and some of the themes Ndlovu explores in her collection.

Immigration and appropriation

Have you ever wondered where the idea for Lyft came from? What if I told you that it all began in Zimbabwe in the early 2000s? “Second Place is the First Loser” is a semi-fictionalised origin story about the founding of Lyft. The story begins with Dineo, a university student who returns to Zimbabwe on a field trip. She’s accompanied by Chad Zimmerman, a fellow student, YouTube influencer and the president of her school’s International Student Union. Dineo is embarrassed by her country’s underdevelopment, especially since Chad is dedicated to documenting all of it for his audience with little to no local context. During their trip, he develops an obsession with Zimbabwe’s lifts, a communal ride-share system that car owners developed to supplement the country’s unreliable transportation service to help members of their communities. Even when told that it’s a favour that Zimbabweans have been doing for each other, when they return to the US, Chad invests in turning the lift system into a for-profit business model, much to Dineo’s horror.

I loved the way Ndlovu approached this nuanced story, and it’s hard to summarise without completely spoiling it. But I found it interesting how she showed that while Dineo’s post-colonial education and perfectionist upbringing allows her to excel in her academics and attend a foreign university, success abroad is not guaranteed, especially when one’s main competitor is popular and privileged enough to appropriate ideas from underdeveloped nations without the risk of backlash.

“Home Became a Thing with Thorns” is another story that centres around immigration, but this time it focuses on how dehumanising the asylum process can be for many refugees. In this tale, a young woman named Rasika is trying to support her friend Jabu through his naturalisation ceremony so that he can become a citizen in a cruel and strange country. They both believe that citizenship here is better than enduring the corruption, disease, poverty, and war in their home country. But to become a citizen requires a personalised sacrifice performed by a naturalisation priest. To become a citizen, Jabu—a painter by trade—has his eyes taken away.

As Rasika waits for her turn, she tries to remain hopeful and not dread the citizenship process, even though she’s seen how much it’s taken away from her fellow refugees. Finally, her time comes, and she steels herself for her own sacrifice.

The casually cruel world in “Home Became a Thing with Thorns” made it one of the most chilling stories in the collection. It’s a reflection of what many refugees and migrants are forced to endure for a better life. After losing so much because of the chaos in their own countries, they are forced to withstand the xenophobia and cruelty of a country that welcomes them with one hand while taking something away with another. It’s a gut-wrenching read, and Ndlovu wields the horror of it masterfully.

Resource and worker exploitation

Ndlovu’s collection also features stories that show how resource and worker exploitation can often go hand in hand. She uses local mythology and folklore creatures to show how damaging these forms of exploitation can be on the environment, and in the fight for human rights.

In “When Death Comes to Find You” a man named Takura is working as a makorokoza or an artisan diamond miner in the Marange Diamond Fields. The Grootslang, a half-elephant half-snake creature which is a protector of diamonds, guards the Marange. Anyone who fails to pay the Grootslang’s mining toll is punished severely.

During one of those long days of work, Takura finds a diamond and pockets it with the intention of paying the Grootslang for it later. He never gets the chance as government forces attack the miners and kill him in the process. He awakens beneath the earth, forced to work through purgatory for the Grootslang. As he labours the story shifts between the aboveground and belowground worlds, showing the origins of diamonds as well as the lengths governments and private companies would go to enrich themselves and keep the artisan diamond trade alive.

“Water Bites Back” is more about environmental degradation and resource exploitation. In this tale, a minister of government is determined to finish a hydro dam project to keep an electoral promise to his constituents and thus guarantee another cycle of his ministerial position. To his annoyance, the dam construction slows to a halt when the local workers complain about carnivorous creatures infesting the waters. Convinced that the Africans are just superstitious, he fires them and hires white workers instead. Only when those workers start dying and the construction team quits does he finally swallow his pride and impatience and go down to the river to speak to the shamanic women living near the half-dammed river. He learns that there are creatures in the water, and the shamanic women have vowed to keep the water safe and clean for them. They try to reason with the minister, but he closes his ears and heart to them. He finishes the dam with force, but the consequences are disastrous.

(Dis)Honouring ancestors and appeasing ghosts

The last general theme in this collection deals with the ways people honour and dishonour their ancestors. But my favourite of these is “Three Deaths and the Ocean of Time”. Nomaqhawe is a university student experiencing some health challenges. She has been having fainting spells, and while unconscious, she would hallucinate about a woman wielding a red axe and demanding that she “Come to the Zamani”. Neither scan nor test can detect anything physically wrong with her, so as a last resort, her doctor sends her to Gogo Pentshisi who tells her that an ancestor is trying to contact her and is trying to give her a task.

Nomaqhawe is sceptical, convinced that a spiritual quest won’t solve her health problems. But when Gogo Pentshisi’s advice corresponds with some information she gets from a guest lecturer at her university, she’s humbled enough to return to complete the quest. By the end of the story, she learns that time travel is possible, and honouring one’s ancestors is another kind of healing.

I loved this story for so many reasons. Firstly, I love that Ndlovu pays reverence to her friend and fellow Voodonauts co-founder Shingai Kagunda in this story. Kagunda’s writing and research has dealt a lot with East African concepts of time, and I loved seeing her as a guest lecturer within this story, thus honoured as a living ancestor.

Mostly, however, I loved how Ndlovu shows that unearthing buried histories and honouring forgotten or misremembered ancestors is an important step to healing from colonialism. While Nomaqhawe has no way of changing the past and preventing the disaster that befell her ancestor, remembering her and ensuring that people in the present knew about her was enough to spark noticeable changes in her community. This story shows the importance and power of storytelling and its role in reparations.

Drinking From Graveyard Wells is one of the strangest collections of short fiction I have read thus far. Its style and genre diversity remind me of Leone Ross’s Come Let Us Sing Anyway, which I reviewed last March. I loved the way Ndlovu interweaves science fiction, Zimbabwean mythology and cosmology, surrealism, and absurdism in this gripping collection of stories.

There were many times where I had to stop my reading and step away from the book because of the accuracy with which she was able to depict human and female experiences within these stories; from the xenophobia-driven dehumanising of immigrants in “Home Became a Thing With Thorns”, to upsetting appropriations and colonial misinformation in “Second Place is the First Loser”. Yet, there is a tenderness that surrounds these stories, a feeling that after all the anger and hurt is poured out, healing and hope will follow. That healing and hope were best encapsulated in stories like “Three Deaths and the Ocean of Time”.

Ndlovu packs a punch with this debut collection, and I’m genuinely excited to see what her future publications will look like given the power with which she jumped onto the scene in her first book. So if you’re looking for a collection of subversive, women-centred stories for this Women’s History Month, give Drinking From Graveyard Wells a try.

Want to learn a bit more about this collection? Check out this episode of the Just Keep Writing podcast with Marshall Carr and L.P. Kindred in conversation with Yvette Lisa Ndlovu.

Nikita Blair is a speculative fiction and creative non-fiction writer. Her work has been featured in Moray House’s Ku’wai magazine, The Guy-ana Annual, and the Com-monwealth Writer’s blog. A collection of her work is featured on her blog, blairviews, where she writes book reviews, essays, and articles on topics of interest. Some of the stories in the collection are available to read for free online. Check out: “Turtle Heart” in Jellyfish Review; “The Friendship Bench” on Tor.com; “Plumtree: True Stories” in the Columbia Journal; “Swimming with Crocodiles” in The Kalahari Review; “Second Place is the First Loser” in the Kweli Journal; Water Bites Back” in Mermaids Monthly.

Some of the stories in the collection are available to read for free online. Check out: “Turtle Heart” in Jellyfish Review; “The Friendship Bench” on Tor.com; “Plumtree: True Stories” in the Columbia Journal; “Swimming with Crocodiles” in The Kalahari Review; “Second Place is the First Loser” in the Kweli Journal; Water Bites Back” in Mermaids Monthly.