The BFI Flare: London LGBTQIA+ Film Festival 2023 which ends today in the UK, featured a Guyanese film on its programme. It is a prominent, international and very influential annual event, which describes itself as “a springtime celebration of queer cinema”. The screening there of a Guyanese film is significant. In fact, the very recognition by such a prestigious festival is itself an achievement, but it goes further because it will expose the work to an international audience and can redound to the development of Guyana’s small and still struggling film industry.

The BFI Flare: London LGBTQIA+ Film Festival 2023 which ends today in the UK, featured a Guyanese film on its programme. It is a prominent, international and very influential annual event, which describes itself as “a springtime celebration of queer cinema”. The screening there of a Guyanese film is significant. In fact, the very recognition by such a prestigious festival is itself an achievement, but it goes further because it will expose the work to an international audience and can redound to the development of Guyana’s small and still struggling film industry.

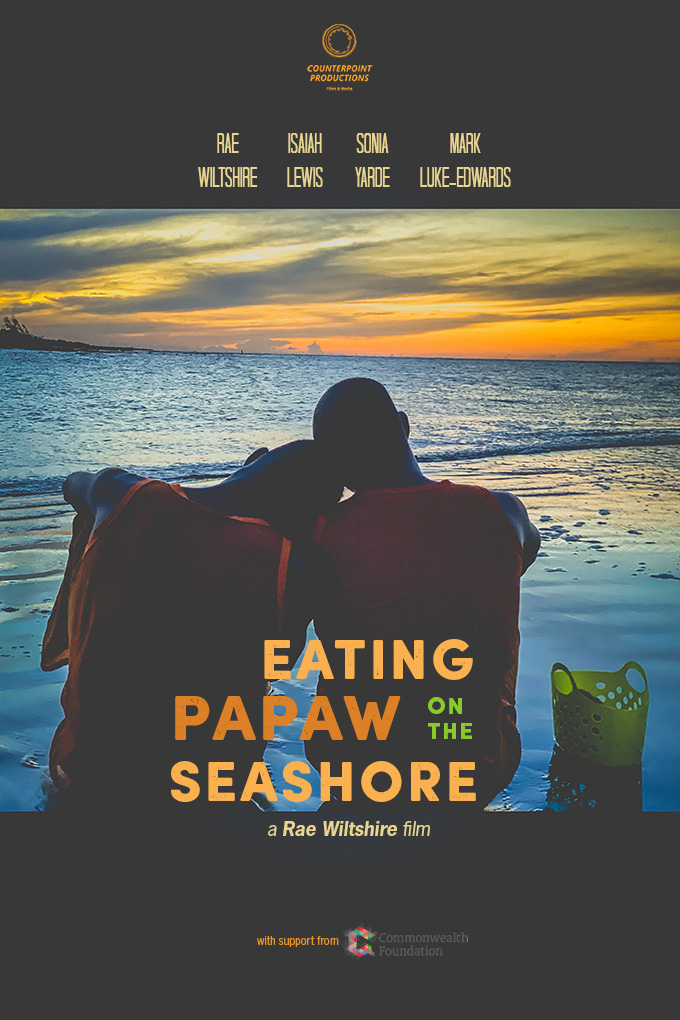

Eating Papaw On the Seashore is a short film by Rae Wiltshire, produced in Georgetown in 2022 by Maribunta Pictures and distributed by Studio Anansi. It was written by Wiltshire and directed by him and Nickosi Layne, with a number of prominent names in its list of credits. These include prolific filmmaker Romola Lucas as Executive Producer, with Wiltshire and Melissa Roberts as Producers and Akbar Singh as Associate Producer.

Burchmore Simon was responsible for sound mixing and design, Sonia Yarde provided script support, Nicholas Singh was storyboard artist with drone footage by Kojo McPherson. The film has quite an effective theme song, “Won’t Let Me Go” by Lerone Souvenir, Jaheim Jones and Rondell Glasgow. It acknowledges support from the Commonwealth Foundation and Third Horizon.

Guyanese film has a long history, including a number of well-known, full-length features for the cinema big screen going back some 50 years. But there were seriously meaningful leaps forward from the time of the then president Bharrat Jagdeo’s Initiative in 2010, led by Paloma Mohamed with short films made and shown at the Theatre Guild. Since then there has been a steady, growing succession of projects, groups and individual efforts in filmmaking slowly claiming a place.

Several new short films emerged in various ventures including CineGuyana and a number of rising artists published work until there is now an unofficial national collection.

Guyanese films were taken to Carifesta in Haiti in 2015, Barbados in 2017 and Trinidad and Tobago in 2019. Lucas facilitated the creation and showing of several works.

Wiltshire’s Eating Papaw On the Seashore is among the most recent, though it is not his first film. It was launched at the New Beginnings Film Festival screened at the Theatre Guild Playhouse on October 8, 2022. This was a new event hosted by the Canadian High Commission which had joined with the embassies of Argentina and Chile in Georgetown to create new opportunities in the Guyanese film industry and develop a creative meeting place for new talent. It supported LGBT films and provided an effective launching for Wiltshire’s new film.

The work and its creators received further support which facilitated its acceptance by BFI: Flare. British High Commissioner to Guyana Jane Miller provided further assistance when she arranged for it to be shown at a fundraising event at the High Commissioner’s Residence. The film was shown to a paying audience and those funds contributed to the expenses of the team for accommodation in London during the festival.

Wiltshire is a playwright, actor, director and filmmaker who graduated from the University of Guyana with a bachelor’s degree in English, minor in Psychology. His first ventures into playwriting were made as a student at the National School of Theatre Arts and Drama from which he graduated with a Diploma. Playwriting, directing and introduction to film were among the courses. After winning prizes at the Theatre Guild and in the National Drama Festival, he won the 2022 Guyana Prize for Drama. He is a former member of the National Drama Company.

Nickosi Layne, a director and actor, is also a member of the National Drama Company. He graduated from the National School of Theatre Arts and Drama and went on to study drama in Trinidad. He, too, won prizes at the National Drama Festival and Theatre Guild.

In his Director’s Statement, Wiltshire declares: “I made Eating Papaw on the Seashore to reflect queer boys as human beings who can fall in love and that’s it is not something to laugh about. It is natural. In Guyana the idea of being gay is a joke. I do not laugh and wanted to reflect human beings on screen. It was important to capture the humanity of a group of people who often do not feel accepted by society”.

Wiltshire is also the lead actor in the film, in which two boys, the lead Asim, and Hasani, played by Isiah Lewis, are in love. Their parents are caring and understanding, but Asim’s father, Abdul, played by Mark Luke-Edwards, does not appear to be totally convinced about their relationship and tries to cool things by sending Asim away to work in Trinidad. On the other hand, Hasani’s mother, Athina, played by Sonia Yarde, is fully supportive and appears to accept her son’s choices without hesitation.

The film is bold and courageous in its portrayal of a young queer couple, but is as sensitive as it is sensuous and unrestrained in a close study of the boys’ amorous relations. Treatment of the parents is careful and believable. Yarde is subtle and convincing as a mother who is not bothered and is able to tell the whole story as an actress with limited time on the screen. The same goes for Luke-Edwards. As Abdul, he is no less supportive, but is a bit apprehensive about what people will think and say about Asim and Hasani. There is some slight lack of clarity in what appears to be suggestions that Abdul is not too sure that his son is gay. He seems to be the film’s deference to a homophobic or unbelieving society.

Nevertheless, the film is advancing an example to society of understanding and accepting parents. Such exemplars, however, are few and rare in Guyanese society. The film’s biggest flaw is the lack of ageing in both parents, who hardly appear much older than their children.

Treatment of the boys is meticulously handled. It hides nothing, is open and courageous, yet subtle and sensitive. Asim is more sure of himself, while Hasani seems more likely to be conscious of social pressure.

The names of the characters are functional, probably symbolic. All but one are Arabic, also with Swahili and Egyptian usage. Asim in Arabic means “protector”, and in the Quran refers to a “shield” or “guardian”. That is a role played by the boy in the film who is more assured than his friend in self knowledge, identity and sexual preference. Hasani, whose name means “handsome”, is more precious but fragile, likely to hesitate because of public opinion.

Abdul is “servant of God”, while Athina is derived from the Greek and means “wisdom”. Pallas Athene or Athena was the Greek Goddess of Wisdom, and indeed Hasani’s mother in the film takes a wise approach.

The film itself shows contact with a Guyanese environment in many ways. The lush landscape, the abundance of water (sea or river), the food and fruits in constant reference. As regards religion, devotees appear in one scene – played by Akbar Singh, Dexter Gardener and Hansraj Arjun – and place offerings in the water as Hindus do, or Kali Mai worshippers to Ganga Mai.

All these are thoroughly focused in the title and main symbol in the work. The fruit pawpaw, common in Guyana, is symbolic. It is a succulent fruit with dozens of seeds; it has a firm outer covering but is soft inside, like Hasani and his hesitant resolve. Pawpaws are always being given to him, and the two boys actually eat pawpaw on the seashore.

The sea represents a wide, unending horizon.

The film is technically accomplished in terms of camera work, sound, editing and costuming, with a director’s gaze that communicates feeling, desire and emotions. Eating Papaw on the Seashore marks a development in the Guyanese film because of its exploits into queer cinema.

Over the past two decades, drama in the Caribbean, such as The Final Truth? By Thom Cross in Barbados; Not About Eve by David Heron, and Basil Dawkins’ Uptown Bangarang, both in Jamaica, explored the society’s unreadiness to appreciate or accept homosexuality. They represented the way the Caribbean was slowly coming to terms with same sex relations and struggling to move out of homophobia. The Final Truth? was bold and courageous, like this film, in its performance, but showed the possible tragedies that existed. Wiltshire’s film dwells on the more positive probabilities.