An interesting article appeared in December 2017 in MoneyWatch on why the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fails as a measure of well-being. The article refers to the World Economic Summit where the then Head of the International Monetary Fund, Christine Lagarde, Nobel Prize-winning economist, Joseph Stiglitz, and MIT professor, Erik Brynjolfsson, considered the GDP as a poor way of assessing the health of economies. The problem is compounded by the fact that we now live in a digital age, and the standard GDP statistics overlook many of the technology’s benefits. The article went to identify the well-known shortcomings in the use of the GDP:

(a) GDP counts “bads” as well as “goods”. When an earthquake hits and requires rebuilding, GDP increases. Similarly, when someone gets sick and money is spent on his/her care, it is counted as part of GDP. But nobody would argue that the country is better off because of a destructive earthquake or people getting sick;

(b) GDP makes no adjustment for leisure time. Imagine two economies with identical standards of living, but in one economy the workday averages 12 hours, while in the other it is only eight;

(c) GDP only counts goods that pass through official, organized markets, so it misses home production and black-market activity. This is a big omission, particularly in developing countries where much of what is consumed is produced at home (or obtained through barter). It also means that if people begin hiring others to clean their homes instead of doing it themselves, or if they go out to dinner instead of cooking at home, GDP will appear to grow even though the total amount produced has not changed;

(d) GDP does not adjust for the distribution of goods. Again, imagine two economies, but one has a ruler who gets 90 per cent of what is produced, while everyone else – barely – subsists on what is left over. In the second economy, the distribution of the GDP is considerably more equitable. In both cases, GDP per capita will be the same; and

(e) GDP is not adjusted for pollution costs. If two economies have the same GDP per capita, but one has polluted air and water while the other does not, well-being will be different but GDP per capita would not capture it.

The article can be accessed at https://www.cbsnews.com/news/why-gdp-fails-as-a-measure-of-well-being/.

Item (d) above is very much relevant to the Guyana situation if one were to substitute ‘a ruler gets 90 percent’ with ’Exxon gets 87.5 percent’. We have argued on several occasions that Guyana is getting mere pittance from the production of crude by the US oil giant. This is especially when account is taken of, among others: (i) what is perhaps the lowest rate of royalty worldwide of two percent; (ii) the grant of extremely generous fiscal concessions; (iii) the absence of ring-fencing provisions that has the potential of inflating costs for the purpose of determining profit oil to be shared equally between Exxon and the Government of Guyana; and (iv) pre-contract costs of US$1.678 billion which have been treated as recoverable costs. The International Monetary Fund had stated that the 2016 Petroleum Sharing Agreement (PSA) is overwhelmingly weighted in favour of Exxon.

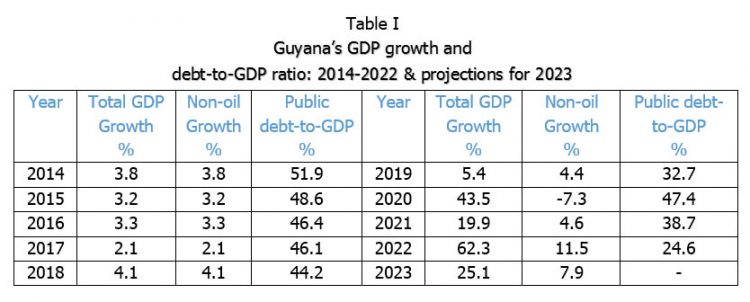

Despite the shortcomings of the GDP as identified above, we continue to boast of Guyana being the fastest growing economy in the world with a growth rate of 62.3 percent in 2022 and a total debt-to-GDP ratio of 24.6 percent. The latter implies that our capacity to contract debts can almost double without any serious risk of default in terms of repayment. As at the end of 2022, the public debt stood at US$3.655 billion. Table I shows Guyana’s GDP growth and debt-to-GDP ratio over the years, with projections for 2023.

From the very inception, we have argued for the renegotiation of the PSA to ensure that Guyana gets a better deal for the production of crude oil resources since our natural resources belong to all of our citizens, present and future, and as such resources ought to be exploited so that they derive the maximum benefit therefrom. Contrary to the views expressed in some quarters, such action does not interfere with the ‘sanctity’ of the contract since Article 31.2 of the Agreement permits renegotiation but with the agreement of all the parties involved.

Last week, Stabroek News reported on the results of the audit of the pre-contract costs incurred by ExxonMobil’s subsidiaries during the period 1999 to 2017. The contract for undertaking the audit was awarded to the UK firm IHS Markit in September 2019 and was to have lasted four months. The purpose of the exercise was to identify expenses that the auditors consider to have been added in error, do not relate to petroleum operations, or for which there is insufficient evidence and transparency to determine the validity of the expenses.

Annex C of the PSA

Annex C of the 2016 PSA states that the amount of US$460,237,918 refers to costs incurred in petroleum operations pursuant to the 1999 Agreement up to 31 December 2015. The Agreement defines pre-contract costs as contract costs, exploration costs, operating costs, service costs, general and administrative costs, and overhead charges as defined in the 1999 Agreement. The Annex further states that Exxon is to be reimbursed ‘such costs as are incurred under the 1999 Agreement between January 1, 2016, and the effective date which shall be provided to the Minister on or before 31 October 2016 and such number agreed on or before 30 April 2017’.

In our article of 22 August 2022, we had stated that an additional estimated US$500 million was expended during the period 1 January to 26 June 2016, giving a total pre-contract costs of approximately US$960 million to be charged as recoverable contract costs. This is in the light of the bridging agreement that links the 1999 Petroleum Agreement with that of 2016. If the effective date referred to above goes beyond June 2016, the recoverable costs will be higher.

Delay in releasing the report

In November 2020, some 14 months later, the Commissioner-General of the Guyana Revenue Authority (GRA) had stated that the report was handed to the Department of Energy to be forwarded to Exxon for its response. And in January 2022, when the matter was raised in the National Assembly, the Minister of Natural Resources had indicated that the audit remained incomplete. However, the final revised version of the report, along with recommendations, was issued in March 2021. This was clearly stated on the cover of the report. Regrettably, after two years, the report is yet to be released to the public.

Government’s explanation

After the Stabroek News article, the Vice President denied that the Government was hiding the report, contending that ‘the report has been with the staff of the Ministry and with the GRA and all their technical people, for the last several years’. Of course, this does not explain why, once the report was issued as a final version, it was not made available to the public.

The following day, GRA issued a statement explaining that the auditors had issued an initial report on 20 March 2020, and what they deemed a final report on 31 July 2020. However, the report did not include Exxon’s response. Thereafter, there were two other iterations of the report between July 2020 and November 2020, again without the written response from Exxon’s subsidiaries. After a review of the various versions of the report, GRA informed the auditors of the following deficiencies:

Absence of recommendations in the report;

Failure to refer to industry standards and good practices for specific findings;

Inaccuracies in the analysis and review of the financial statements;

General inconsistencies and deficiencies; and

Failure to address concerns raised by the Government’s representatives.

Accordingly, GRA requested the auditors to further revise their report to take into account the above concerns and resubmit it for transmission to Exxon’s subsidiaries by 3 February 2021. As indicated above, the auditors issued the final version of the report in March 2021 which include recommendations. The report was transmitted to Exxon on 2 July 2021. Since then there has been on-going correspondence between the Ministry of Natural Resources, Exxon and the auditors. GRA also indicated that when all the issues are resolved, the findings of the auditors will be released to the public.

Notwithstanding the above explanations, we cannot over-emphasise that it has been two years since the auditors issued the financial version of their report, and discussions involving the Ministry, Exxon and GRA are still on-going. However, the fact that no further revisions to the March 2021 report have so far been made, would suggest that the auditors are standing by their report. This is what the World Economic Forum has to say about the auditors in terms of their reputation:

IHS Markit (NYSE: INFO) is a leader in information, analytics and solutions for the industries and markets that drives economies worldwide. The company delivers information, analytics and solutions to customers in business, finance and government, improving their operational efficiency and providing insights that lead to well-informed confident decisions. IHS Markit has 50,000 key business and government customers, including 80% of the Fortune Global 500 and the world’s leading financial institutions. Headquartered in London, HIS Markit is committed to sustainable, profitable growth. (https://www.weforum.org/organizations/ihs)

We urge the Government to release the report to the public not only in the interest of transparency but also because of its obligation to keep citizens informed of the latest developments in the oil and gas sector. We must note that had it not been for the efforts of the Stabroek News, we might not have heard from the Authorities as regards the status of the audit of Exxon’s pre-contract costs, except to be told for yet another time that the audit is still on-going.

Highlights of the report

We now turn to the highlights of the report that was prepared by the most senior officials of IHS Markit – Andrew Day (Managing Director), Muhammed Hannanali (Associate Director), Paul Ferguson (Senior Advisor), and Tarun Ohri (Senior Advisor). The following are the key findings, as gleaned from the Executive Summary:

The actual amount claimed as recoverable costs was US$1.678 billion covering the period 1999 to 31 December 2017;

The Government of Guyana has reasonable grounds to dispute $214.4 million or 12.8 percent of the total cost recovery claimed by Exxon’s subsidiaries. If these charges are removed from the cost recovery statement, Guyana’s share of profit oil will increase by US$107.2 million. This is in addition to certain overhead adjustments made by Exxon’s subsidiary EEPGL and included in the cost recovery amount;

Of the amount of $214.4 million referred to at (b), $34.3 million is considered ineligible, while $180.1 million lack adequate supporting documentation;

Of the total cost recovery expenditure, amounts totalling $1.218 billion, or 73 percent, were incurred between 2016 and 2017;

Since the 2016 PSA does not contain ring-fencing provisions, the cost recovery amount includes continued exploration and developments costs for all fields within the Stabroek Block;

Almost 50 percent of inter-company charges was included in the cost recovery statement;

The cost recovery statement had limited transparency and fell short of the expected level of accounting documentation;

Despite several requests for clarification in relation to the inter-company charges, EEPGL unable to provide adequate justification for these charges. The auditors have recommended that these should not be included as recoverable costs;

Amounts totalling $31.43 million were included in the cost recovery statement but were not reflected in the main accounting record, the General Ledger. These amounts relate to payments made by the Co-Venture partners, many of which were incurred prior to the Co-venture partners being signatories to the PSA. The auditors concluded that the validity of these costs for inclusion in the cost recovery statement had not been demonstrated by EEPGL and should therefore be excluded from the statement;

EEPGL confirmed that data prior to 2004 was not available as it was purged in accordance to their internal data retention policies. As a result, a summary of costs incurred during this period was used for inclusion in the cost recovery statement;

EEPGL did not do enough to keep the Government of Guyana appraised of the activities and costs associated with the development. In particular, the annual work programme and budget submission did not meet expectations, and no justifications were provided at the end of each year for changes in scope or cost overruns. Both of these are requirements in the PSA; and

Insurance certificates were not provided to ensure that full coverage has been maintained throughout the audit period. Although each partner procurred coverage for its share of the block interest, only EEPGL has provided premium details and invoices. As a result, the auditors were unable to confirm that Hess and CNOOC were meeting their responsibilities in this regard.

Next week, we will continue our discussion on the report.