Look in the glass and tell the face thou viewest,

Now is the time that face should form another,

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

For where is she so fair whose unear’d womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond shall be the tomb

Of his self love to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother’s glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime;

So thou through windows of thy age shall see,

Despite of wrinkles, this thy golden time.

But if thou live remembered not to be,

Die single and thy image dies with thee.

Sonnet 116

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

O no, it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wand’ring bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks

Within his bending sickle’s compass come.

Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks,

But bears it out even to the edge of doom.

If this be error and upon me proved,

I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

65

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea,

But sad mortality o’ersways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O how shall summer;s honey breath hold out,

Against the wrackful siege of battering days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong but Time decays?

O fearful meditation, where alack,

Shall Time’s best jewel from Time’s chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back,

Or who his spoil of beauty shall forbid?

O none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love shall still shine bright.

18

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm’d;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course, untrimm’d;

But thy erternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st.

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

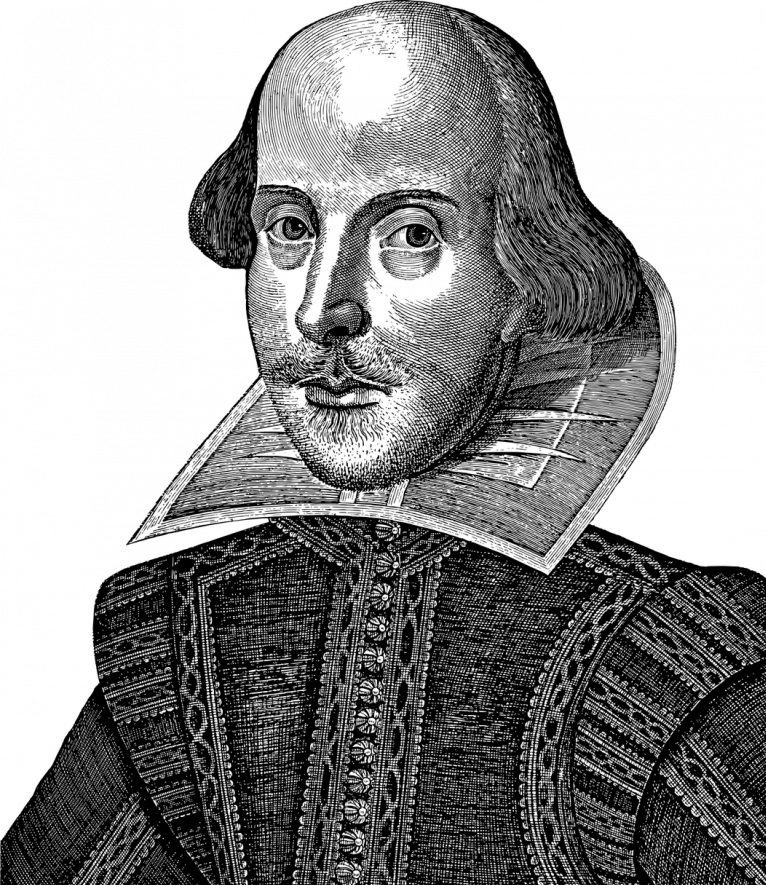

Today is William Shakespeare’s birthday. We mark it each year to celebrate the literature of a great poet and playwright who even his contemporaries were describing as a man not only “of an age, but for all time”. His first works to appear in print were the two long narrative poems, “Venus and Adonis” (1593) and “Lucrece” (1594), and the tragic play Titus Andronicus in 1594. Today, the critics declare: “it is clear that all three indicate the ambition of the young poet to vindicate his claims to literary distinction. They herald, indeed, a career of poetry, not of hack-work for the commercial stage”, but “as that of a man of letters from the beginning to the end”.

Stratford, on the banks of the River Avon in the County of Warwickshire, England, where he was born on April 23, 1564, was a flourishing country town at that time. Today it is a bustling small city, overbrimming with tourism, from the serene sight of the regal swans floating majestically on the river to the teeming crowds flocking his birthplace, buying historical tokens and cueing up outside the four theatres, one of which is the home of the Royal Shakespeare Company.

It is the centre of a major tourist industry which multiplies in intensity and events on the anniversary in April each year, overflowing into London , where a replica of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre has been built close to the site of the original Elizabethan structure. This extensive annual festival, which is in progress at this moment, added to commemoration activities in other parts of the world, will remain as additional proof of Shakespeare’s greatness, importance and immortality.

His superiority as a playwright was acknowledged during his lifetime by friend and foe alike, judging from the comments of his contemporaries. He was ahead of them both in advantages and accomplishments. He developed a thorough knowledge of the stage, having worked in companies as an actor before advancing as writer, director and producer, ending up as part owner of the Globe Theatre and the Company known variously as Lord Chamberlain’s Men and The King’s Men. This experience and grounding enriched his plays, which contain several internal references to and metaphors of the theatre. He was a favourite of Royal patrons, both Queen Elizabeth and King James.

Yet, above the advantages gained from being a technician, he was an exceptional poet. He was publishing poetry for as long as he was putting out drama and was extraordinarily innovative in both disciplines. Like his contemporaries, he adopted the classics, but the extent of his innovation and originality caused forms to emerge which became known as Shakespearean tragedies and Shakespearean comedies. Such were his adaptations of the English sonnet that it became known as the Shakespearean sonnet.

Shakespeare begins with the English sonnet and interrogates it in shaping the verse form. At the same time he engages the Petrarchan sonnet , which he debunks. In this 14 line poem there is a fixed rhyme scheme which divides it into an octave, consisting of the first eight lines, and a sestet, which is the next six lines. In the English version used by Shakespeare, this structure is further divided into three quatrains and a couplet.

Each poem advances an argument. It begins in the first four lines and continues over the next four. There is then a shift in focus, delivering the third part of the argument, which then ends in a concluding couplet. These last two lines deliver the final coup in the argument, which in most cases takes a sharp turn from all that has been said in the previous 12 lines.

In Sonnet 18, for instance, the poet is arguing that I cannot compare you to a summer’s day because the summer day is short-lived, cannot overcome the effects of time, and has several imperfections. You cannot be praised by the comparison because you rise above all its imperfections. But then he paradoxically closes his argument by saying you possess the qualities of summer, but in you, these qualities last forever. He then drives home the argument in the last two lines, which clinch it by declaring that the lines of his poem will live forever and you will live with them, outlasting everything, including the summer’s day. This kind of startling claim is typical of the Shakespeare sonnet, which often concludes by claiming that his verse will be immortal and has the power to give eternal life to its subject.

This kind of argument in the sonnet is sharpened and emphasized by Shakespeare, who also often uses the sonnet to debunk the poetic conventions of the times. One such is the Petrarchan convention in which the poet praises his mistress in exaggerated metaphors and comparisons which make her out to be most beautiful and most perfect. Comparisons to such things as summer, the beauty of summer and all its favourable qualities abound in the Petrarchan conventions. Shakespeare, however, ridicules this practice, and, in fact, in “Sonnet 18” refuses to adopt such comparisons. He usually finds a clever counter-argument to prove the beauty and perfection of his lady, which in several cases, he anchors in the lines of his poetry, which will live forever.

After 400 years, these prophetic claims of immortality seem quite justified. Shakespeare’s works have surely conquered time and remain relevant and important today. This ability to hold the interest of readers and audiences over all these centuries, and to be the centre and focus of all these activities and celebrations today is what proves the greatness of this poet-playwright whose works have not only been “of an age, but for all time”.