By Roger Seymour

The Windrush Generation

Five years ago, the story of the children of the Windrush Generation dominated British headlines, and the heavily embarrassed UK government apologised to thousands of people who had arrived in Britain as children decades before, and had become victims of the tightening immigration system. These adults, some of whom had migrated to Britain on their parents’ documentation, or never had their births registered, had never formally applied for citizenship or a passport. Despite, in most cases, having spent almost their entire life in Britain, they suddenly found themselves incorrectly identified as illegal immigrants, and unable to work or have access to health services. The situation was further compounded by the fact that in October 2010, the Home Office had destroyed thousands of landing card slips on which the arrival dates of many of the Windrush Generation had been recorded.

After the catastrophic destruction of many parts of Britain during World War II, citizens of the Commonwealth were invited to help fill labour shortages and rebuild the economy of the ‘Mother Country’. Thousands of persons from the Caribbean and British Guiana seized the opportunity and many arrived in England on board the ship Empire Windrush, formerly MV Monte Rosa, a German cruise ship, which was launched in Hamburg, on 13th December, 1930. The ship, which was requisitioned by the Nazis at the outbreak of the war, was used initially to transport troops for the invasion of Norway and later served as a prison ship for the deportation of Norwegian Jews. It was captured by the British in 1945 as a prize of war and renamed in 1946. On 22nd June, 1948, the Empire Windrush arrived at Tilbury Docks, down river from London, on board were over 800 people from the Caribbean, the first significant wave of migrants. The streams of arrivals later found employment in the National Health Services and British Rail, among other fields.

According to Britain’s National Archives, almost half a million people from every corner of the English-speaking Caribbean migrated to the UK between 1948 and 1970. Under the 1971 Immigration Act, all Commonwealth citizens already living in Britain were given indefinite leave to remain. However, the Home Office never kept any records of who were the beneficiaries of this Act, or issued any paperwork confirming it.

Caryl Phillips

“I was born in St Kitts in 1958, at a time when Caribbean people were migrating to Britain in terrific numbers. My parents were very young, in their early 20s, and they decided to go to England for all those opportunities: education, the possibility of more money, better economic prospects. I left as a piece of portable luggage in their arms and wound up in Britain as a four-month-old kid. I grew up in Britain without any visual memory of the Caribbean. What I had was a notion of the cooking, the accent in the house, a total obsession with cricket on the radio and the TV as a kid.” This was how Phillips described his early life in an interview published in the May/June 2011 edition of Caribbean Beat.

Phillips arrived at Queen’s College, Oxford in 1976, where among the things he discovered was that his peers “were all public school boys” and they didn’t share his sophisticated interests in beer, women and football. Having grown up on council estates in the industrial cities of Leeds and Birmingham, at university new friends, the landed gentry, exposed him to the world of 40-acre spreads. Other contemporaries, who were of less modest origins, lived in villages, where the choices for nightly entertainment ranged from going to the pub to watching television to reading a book.

At Oxford, where Phillips switched from Psychology to English, he directed numerous plays and worked as a stagehand during summers at the Edinburgh Festival. Upon leaving Oxford, he decided to pursue writing as a career. His initial offerings were three plays, “Strange Fruit” (1980), “Where There is Darkness” (1982) and “Shelter” (1983). His first novel, “The Final Passage” was published two years later, followed by “A State of Independence” (1986).

Playing Away

It was against this backdrop that the young playwright/novelist sought a canvas to pit the urban West Indian immigrant raised in council flats in an inner city environment against rural English society to reveal what they had in common. It is quite salient that Phillips selected the game of cricket, which he never gravitated to, instead of football in which he had developed serious interest. Growing up near to ‘the cathedral’ on Elland Road, the home of Leeds United, during the heyday of Don Revie managed teams in the late 1960s and the early 1970s, Phillips became a lifelong Leeds fan.

Why cricket? Phillips was keenly aware of the role cricket played in the life of the Windrush Generation. The Caribbean migrants’ aspirations for a better life were often jolted by the harsh conditions they met on arrival in the ‘Mother Country.’ The weather was cold, bleak and damp. The appearance of the sun was not always synonymous with warmth. The ominous face of racism seemed to lurk everywhere: at the workplace or on the street in the form of the Teddy Boys. Searching for housing they would be confronted with signs that read “No Blacks (or Coloureds), No Dogs, No Irish.”

The one place where the Windrush man could hold his head up and high, and strut proudly, was the cricket field. Growing up, no doubt Phillips would have witnessed his father and his friends’ wild jubilation during the West Indies’ frequent visits to England, between 1963 and 1984. The WI sides, boasting the likes of Gary Sobers and Rohan Kanhai (missed 1969 Tour), dispatched strong English teams in 1963 and 1966 by 3 – 1 margins, while an ageing side succumbed 2 – 0 in 1969, before rebounding with a convincing 2 – 0 performance in 1973. The Clive Lloyd teams from 1975 to 1984, included the Master Blaster Viv Richards and a fearsome pace quartet. They captured the first two World Cup competitions, and never lost a Test match, winning 3 – 0 in 1976, and 1 – 0 in 1980, before sweeping the English 5 – 0 in 1984. The Conquistadores XI, Phillips’ bunch of casual players, would be imbibed with an air of confidence no matter where he chose to locate the Sunday match. In his words; “Which team would play away? It was easy. The team that had been playing away the longest.”

Described in one review as “a gentle humourous film”, “Playing Away” reveals Phillips’ subtle genius at work in almost every line, every scene. There is no padding, no fluff. Phillips presents the essence of the Caribbean man through several characters on the team.

The film was directed by Trinidadian Horace Ove, a long-time resident of England and independent filmmaker, who did magical work with the blending of his camera angles, as he breathed life into Phillips’ script. It was his second feature film after “Pressure” and several documentaries including the highly acclaimed “King Carnival” (1973) on the history of the Trinidad carnival

Despite living in England for an extended period of time, Willie Boy, the team’s captain, played by the late Guyanese Norman Beaton, remains West Indian to the core. Everyone knows someone or has an uncle who still has the same tone and accent after living abroad for 50 years. In a brilliant performance, Beaton held the team (and the film) together as Phillips presented our foibles and strengths.

At the Friday night meeting at the pub to confirm arrangements for the trip the next day, the casual / borderline lackadaisical West Indian approach is on full display; some members of the team are late and some never appear. The arrangements appear to be haphazardly made and an aura of disorganisation prevails. The younger generation, brought up in England, are a confused lot. Jeff, Willie Boy’s son, doesn’t know which world he lives in. He is married to an Englishwoman and they have a young baby, so Jeff can’t stay and leaves almost immediately, after confirming his participation. Errol, a young upstart, is disrespectful to Willie Boy, who is quite willing to take him on physically, but are kept apart by team members.

Back in his council flat, Willie Boy and his side-kick, Robbo, over tumblers of whisky, discuss the troubling subject of re-migration. Willie Boy’s wife is already ‘Back Home’ checking out the scene, while Robbo’s wife has informed him that if he ventures home he shouldn’t bother to return. The debate is quickly aborted as neither wants to deal with the reality of the paradox they face. Return to what? Stay in England, for what? The overlapping of two worlds is the dilemma of the Windrush Generation.

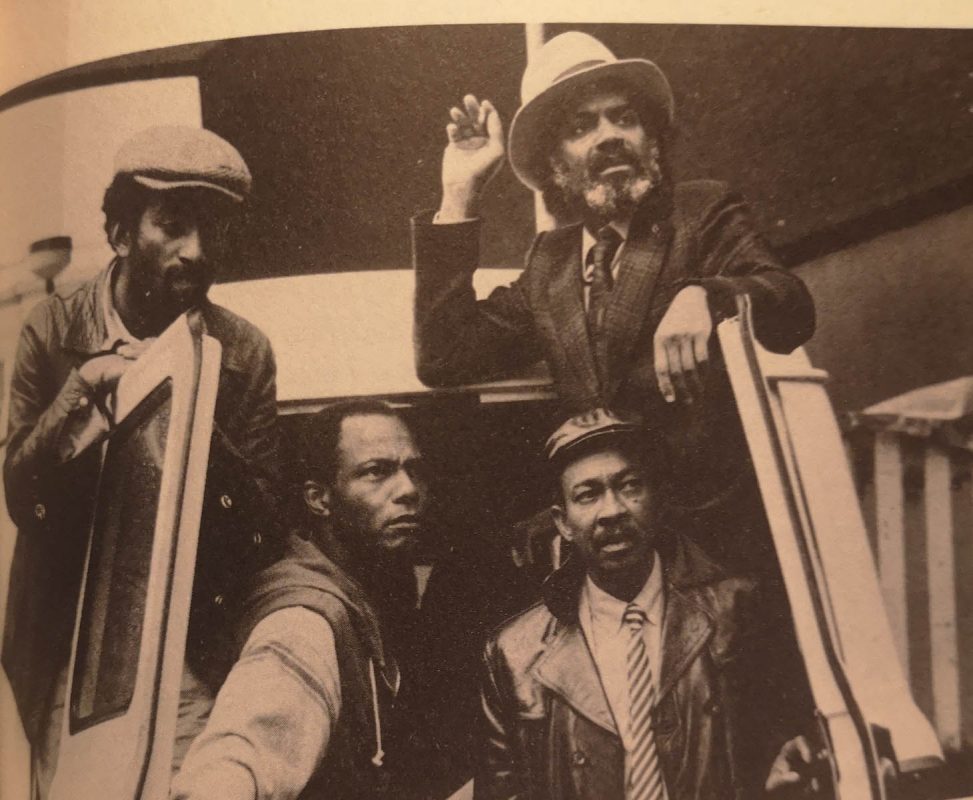

On Saturday morning, the tardiness continues, as the team awaits the arrival of the stragglers, including Jeff. In response to his father’s concerns, Jeff asks, “You know anyone in the mafia?” The clash of the two cultures can generate all kinds of thoughts. As to be expected, the boys from South London are soon lost, map reading is beyond them, and they have to resort to seeking directions to the village.

There are hectic preparations in the fictitious, gentrified Suffolk village of Sneddington (could be the name of a village in an Enid Blyton or Billy Bunter book) for the friendly cricket match, the highlight of its “Third World Week” activities. Sneddington’s all-white residents include a mixture of well-meaning older folk of the public school genre, hostile country youth, a vicar and a town constable, complete with bicycle; the latter two completing the Enid Blyton analogy.

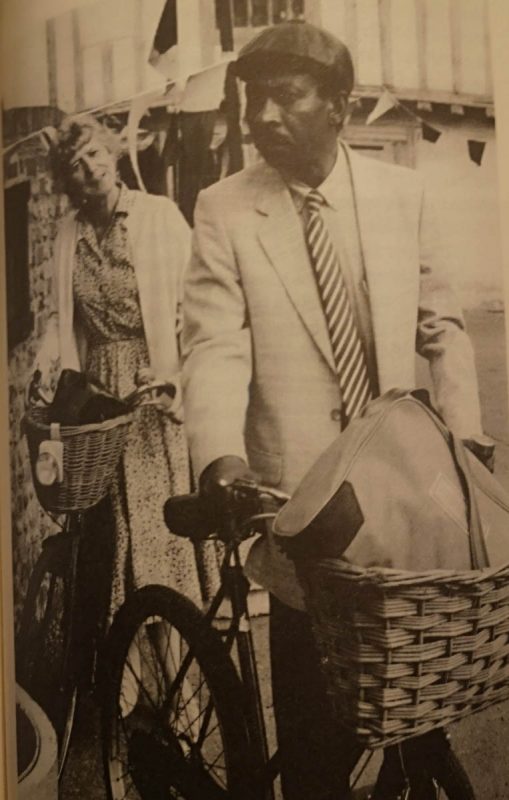

The arrival of the Conquistadores’ rented minivan is greeted with the playing of “Island in the Sun” by a small brass band. The welcome ceremony is awkward as neither seems to know how to deal with the other. As Saturday afternoon evolves into evening, tension between the two sides mounts. Willie Boy, presented with an old push bike by Miss Rye, the host with whom he is billeted, does not fare too well on his bicycle tour of the surroundings, and eventually falls asleep on the war memorial in the village square. Awakening in the evening, Willie Boy looks for his daughter and proceeds to the pub and then the tavern where, under the influence and obviously disturbed by his missing daughter, he experiences the threat of ejection before the timely intervention of the village team’s captain. A snapshot of the prejudice the Windrush Generation had to endure.

During the Sunday morning church service, Robbo worries as both Jeff and Willie Boy are missing. The former has abandoned the team, departing his billeted residence in the early dawn hour without informing anyone; Jeff is a totally confused young man. The latter, drunk, spends the night asleep in the village cemetery, but is awakened and taken for breakfast by Godfrey, a villager, whose wife Marjorie is the weekend’s organiser.

Willie Boy recovers in time for the match and rallies the team, which is short two players, with a blunt pep talk. “… And I don’t have no time to make joke with these people. A cricket field don’t be no place to separate the good from the bad; it’s us and them. No gentleman shit out there. We play, we win, we gone. But most of all we win, you hear?” There is a pause as everyone looks at Willie Boy. This is serious business. There is a cricket match to be won.

The village team wins the toss and rattles up a score of 103, and the Conquistadores are soon in deep trouble at 18 for four. Errol, the upstart, and Willie Boy dig in, rallying the team to 75 for four, before all hell breaks loose, as Godfrey, once again, turns down an LBW appeal against Errol. The bowler confronts Errol, who stands his ground, as a yelling match of the younger generation ensues. Soon six members of the village team are stomping off the field, as Derek is at his wits’ end to hold the crumbling XI together. It’s a hopeless situation for the five villagers left on the field, as the boys from south London, who appeared likely to lose, romp home.

Marjorie thanks the Conquistadores XI for making the trip (Phillips providing a subtle reminder that the women were more welcoming of the Windrush Generation).

As the team coach prepares to leave the village green, Willie Boy laments the lack of an offer of a drink at the pub, to which Robbo responds, “But these people got their difficulties, man.”

“And you don’t think we got ours?” Willie Boy snaps.

The film ends with the minivan arriving in Brixton, in the Sunday twilight.

Postscript

Caryl Phillips has penned 12 novels to date and three more plays. His numerous awards include the James Tait Black Memorial Prize (1994) and the Commonwealth Writers Prize twice (2004, 2006)