The Commonwealth Caribbean Association of Integrity Commissions and Anti-Corruption Bodies (CCAICACB) held its 9th Conference last week at the Arthur Chung Convention Centre. The Minister of Parliamentary Affairs and Governance gave the opening remarks in which she stated that Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) painted the Caribbean region as a “haven for corruption”; and the CPI scores and rankings are based on the perception and assessment of two to three persons who were not selected by the electorate. She also sought to question the methodology used in the compilation of the Index and indicated that the Government of Guyana does not recognize the Index.

The Minister further stated that in the past the CPI scores and rankings showed that the most corrupt countries are south of the Equator and that this reflects ‘prejudices and biases against persons in the developing world’. This statement is not dissimilar to the response that the Vice President had given at the interview with Vice News on the question of corruption in Guyana. He had stated that ‘we do have a real corruption in countries as ours too. This is like a blacklisting index. The darker you are, the lower you are on the Index’. The Minister of Finance, who also addressed the gathering, was more circumspect in his remarks, avoiding any criticism of the CPI and instead choosing to refer to citizens’ participation as a means of reducing corruption in the public sector.

On the other hand, the Assistant General Secretary of the Commonwealth urged member countries to embrace the findings of investigative journalism as they work to stamp out corrupt practices in their countries.

He noted that in the era of social media the work of investigative journalism has suffered because of the inability of media houses to pay good investigative journalists to produce in-depth reporting.

CCAICACB’s Chairperson also called on countries to support the work of the media and investigative journalism. He said that in order to make headway in their fight against corruption, there is a need to address the climate of fear that exists in reporting under the guidelines of whistleblowing and anti-bribery legislation.

In today’s article, we discuss some of the above comments as they relate to the CPI. As stated in previous articles, given the opaque nature of corruption, it is extremely difficult to measure actual levels of corruption in a society.

An alternative therefore had to be found that is generally acceptable, with the primary intention of creating an awareness of the adverse effects of corruption and providing a basis for actions to be taken to bring about improvements. It is against this background that the CPI was developed. The Index is calculated based on surveys carried out of the perceptions of knowledgeable people, such as senior businessmen and political country analysts, of perceived levels of corruption in a country. The results, when computed using statistical methods, correlate well and provide some confidence about the actual levels of corruption.

Caribbean countries a “haven of corruption”?

This is an extraordinary statement, especially coming from someone in charge of governance arrangements in Guyana and with responsibility for overseeing the implementation of both the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption (IACAC) and the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC). She is also a leading member of Guyana’s Public Accounts Committee (PAC) which is five years in arrears in reporting on Committee’s scrutiny of the public accounts; and was most instrumental in amending the size of the quorum for PAC meetings, only to see less meetings being held for want of a quorum because of the absence of government members.

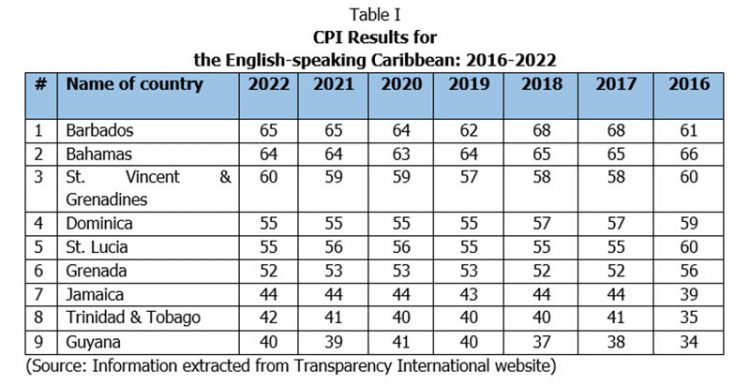

The truth of the matter is reflected in Table I which shows that, except for Guyana, Trinidad & Tobago, and Jamaica, all the other countries in the English-speaking Caribbean have scored well on the CPI over the years, comparable with several of the developed countries, including the United States, Israel, South Korea, Portugal, Spain, Georgia and Costa Rica.

Is the CPI based on perceptions and assessments by one or two individuals?

The assessment is done by reputable organisations, such as Economic Intelligence Unit, World Bank, World Economic Forum and Varieties of Democracy. The CPI aggregates data from several different sources that provide perceptions of businesspeople and country experts of the level of corruption in the public sector. As in previous years, the 2022 CPI was calculated using 13 different data sources from 12 different institutions. For a country to be included in the CPI, there must be a minimum of three such sources.

Should the compilation of the Index be done by persons selected by the electorate?

Since the CPI is about corruption in the public sector, it would inappropriate for elected officials to be involved in the assessment. It is the majority of elected officials who are responsible for the management of the affairs of the State and therefore for them to assess perceptions of levels of corruption for entities over which they have oversight responsibilities, will present a serious conflict of interest. Indeed, they will have a vested interest in providing a favourable rating and ranking of the country being assessed. It is mainly for this reason that reputable institutions that competent, independent and politically neutral, are involved.

Is it true that countries south of the Equator are perceived to be the most corrupt?

The Minister’s assertion cannot be substantiated. Countries to the south of the Equator that performed well on the 2022 CPI include New Zealand (87 ), Australia (75), Chile (67), Uruguay (74) and Botswana (62). On the other hand, countries to the north of the Equator that performed poorly include Jordan (47), Armenia (46), Romania (46), China (45), Hungary (42), Kuwait (42), Vietnam (42) and Kosovo (41).

Is there something wrong with the methodology used for compiling the Index?

The 2022 CPI was based on surveys carried out of 180 countries using, as indicated above, data gathered from 13 sources by 12 different institutions. These data sources were required to respond to specific questions relating to the following:

Bribery;

Diversion of public funds;

Use of public office for private gain without facing consequences;

Ability of governments to contain corruption and enforce effective integrity mechanisms in the public sector;

Red tape and excessive bureaucratic burden which may increase opportunities for corruption;

Meritocratic versus nepotistic appointments in government;

Effectiveness of criminal prosecution for corrupt officials;

Adequacy of laws on financial disclosure and conflict of interest prevention for public officials;

Legal protection for whistleblowers, journalists and investigators when they are reporting cases of bribery and corruption;

State capture by narrow vested interests; and

Access of civil society to information on public affairs.

Each data source used to construct the CPI must satisfy a number of criteria for it to be considered a valid source, and statistical methods are used to arrive at a country’s score. This is done by subtracting the mean of each source and dividing it by the standard deviation of that source in the baseline year to ensure comparability with previous years. A country’s CPI score is then calculated as the average of all standardised scores available for that country.

Should governments not recognize the results of the CPI?

Any government that refuses to recognize the CPI does so at its own peril since the Index is an internationally recognized yardstick for assessing corruption in a country. The United Nations, World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the Inter-American Development Bank, the European Union and other multilateral institutions recognize the CPI as an authoritative pronouncement of corruption worldwide. Overseas organisations wishing to do business in a country look at the CPI as an important indicator in deciding whether or not to proceed.

As we have stated on several occasions, countries that share a deep concern for good governance, including transparency and accountability, view the index as an important measure in their fight against corruption. An improvement in a country’s CPI score as well as its ranking is considered an indicator of a reduction in the level of corruption. The first step in the fight against corruption therefore must be the acknowledgement of the existence of corruption and the extent to which it is perceived to exist. The failure to do so will only serve to embolden those who are bent on indulging in corrupt behaviour that enriches the few at the expense of the vast majority of the citizens.

Whistleblower protection

As a signatory to the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption, Guyana is required to create, maintain and strengthen the system to protect public servants and private citizens who in good faith report acts of corruption to the relevant authorities. Since 2012, we have been advocating the promulgation of legislation to protect whistleblowers. However, it took 22 years for legislation in the form of the Protected Disclosures Act 2018 to be passed to give effect to this important provision so vitally necessary in the fight against mismanagement, corruption and unethical behaviour. To compound matters, after more than four years, the Act is yet to be operationalized via the issuance of the relevant Order by the Minister of Legal Affairs.

The failure to offer legal protection for whistleblowers acting in good faith and in the public interest, will only deter persons having information about the abuse and misuse of authority, from coming forward and make disclosures to the appropriate authorities, for fear of discriminatory action taken against them. We have already had two recently recorded cases where disciplinary action was taken against whistleblowers.

Access to information

Access to information on government programmes and activities is a fundamental right of all citizens. It is an essential element of every system of democracy and facilitates transparency and accountability, indeed good governance practices. In November 2006, draft legislation on access to information was presented in the Assembly. It, however, languished there for five years, and it was not until June 2011 that a new version was presented. This new version was passed in the Assembly on 15 September 2011 and assented to by the President on 27 September 2011.

As of March 2013, the Act had not yet to be brought into operation. The Advisor on Governance had contended that the delay was due to difficulties in finding a Commissioner, budgetary constraints and lack of information on government websites. Faced with criticisms from the United States Government, the Organisation of American States, the International Press Institute, and Transparency Institute Guyana Inc. for failure to operationalize the Act, the then President issued the relevant Order on 10 July 2013. Five days later on 15 July 2013, he appointed two-term former Attorney General to the position of Commissioner.

The Commissioner is to act as a clearing house for processing requests. It is unclear why our legislators opted for this centralized model as opposed to a decentralized one whereby individuals and organisations can approach government agencies directly instead of the Commissioner. By the time the information is made available, its relevance for decision-making and other purposes may very well be lost. In Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago, for example, the legislation on access to information does not provide for a Commissioner of Information; and it is the responsibility of individual government agencies to make available relevant information to the public and to respond to requests for information.

A key requirement of the Act is the preparation and submission of an annual report to the Assembly setting out, among others, the number of requests made to the Commissioner and how they have been dealt with. However, to date, no such report was tabled. In the circumstances, the effectiveness of the legislation governing access to information on government programmes and activities could not be determined.