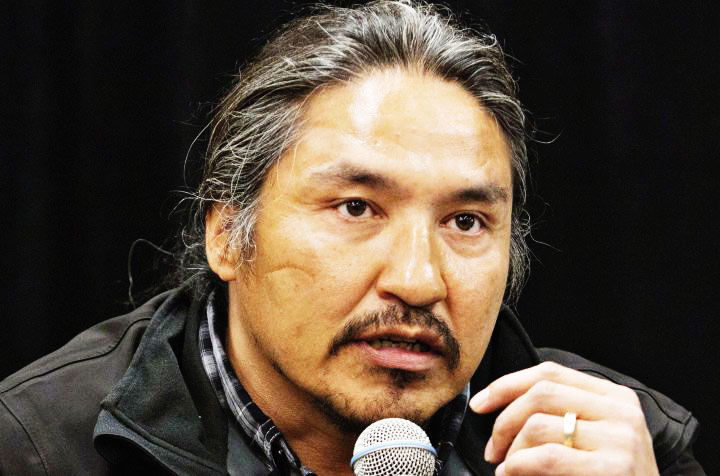

(Reuters) – In early February, Chief Allan Adam of the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation in northern Alberta started fielding calls from community members after the provincial regulator revealed toxic wastewater had been leaking for months from a tailings pond at Imperial Oil’s IMO.TO Kearl oil sands mine.

Many in the community hunt and fish downstream of Canada’s huge bitumen mines, and wanted to know if the game meat in their freezers was safe to eat.

“I just told them throw the meat away,” Adam said. “Don’t even feed it to your dog.”

The seepage was discovered by Imperial, a unit of Exxon Mobil XOM.N, last May but local communities only learned the water contained tailings in February, after a second leak occurred.

Imperial CEO Brad Corson apologized for the leak and the lapse in communication during questioning at a parliamentary committee in Ottawa last week.

In response to Reuters questions, Imperial said it is addressing the seepage by drilling extra monitoring and collection wells, and there is no indication of impacts to wildlife or fish.

The leaks have reignited concerns among First Nations, policy makers and environmentalists about Canada’s vast oil sands tailings ponds, which reached a volume of 1.35 billion cubic metres in 2021.

A slurry of sand, clay, residual bitumen and water containing naphthenic acids and metals, tailings ponds can kill birds that land on them and are costly and complicated to clean up. Oil sands mining companies are responsible for decontaminating the roughly 30 man-made lakes that hold decades-worth of wastewater, and eventually restoring the landscape.

Bitumen mining, which started in 1967, contributes around a third of Canada’s 4.9 million barrels a day of oil production. Three companies operate the eight mines running today: Imperial, Suncor Energy SU.TO and Canadian Natural Resources Ltd CNQ.TO.

But after decades of mining, companies have barely started land reclamation and regulators, policymakers and Indigenous communities are struggling to decide how best to deal with the waste.

Now the Kearl leak has stoked opposition to a proposal industry and the Canadian government have been working on since 2017: developing effluent regulations that would allow companies to release treated tailings water into the Athabasca River, which feeds one of the world’s largest freshwater deltas.

The Mining Association of Canada (MAC) says oil companies have the ability to decontaminate tailings water and need to release it – at a rate of 2% of the Athabasca’s annual flow – to reclaim the ponds.

But some Indigenous communities and environmental groups say they do not trust industry to make the wastewater safe. They are urging Ottawa to slow the development of the regulations, due by 2025, and overhaul how tailings are managed.

“There were already concerns about tailings seeping into the river – this (leak) heightens the fear, the concern and the lack of trust,” said Melody Lepine, director of government and industry relations for the Mikisew Cree First Nation.

Lepine said her community was questioning whether the wastewater could be removed from the region altogether for disposal. Other possibilities include pumping some of the water into deep wells or storing it in underground lakes, experts said, but the sheer volume of accumulated tailings means there are no good options.

Imperial declined to comment on concerns about the effluent regulations. Canadian Natural did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Industry has not said exactly how it would treat tailings water before release into the Athabasca. Rodney Guest, director of water and closure at Suncor, said it will take three or four years after the effluent regulations are finalized for industry to develop a treatment plan.

BROKEN TRUST

Imperial first noticed pools of orange surface water in four areas near its Kearl site last May. The company told the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) and notified local First Nations, but did not update communities when testing showed the water contained tailings.

Ottawa only learned of the seepage nine months later when the AER issued an environmental protection order, after a second spill of 5,300 cubic meters from a Kearl drainage pond.

The AER’s CEO Laurie Pushor apologized on Monday for poor communication with Indigenous communities.

First Nations say the Kearl leak and its handling by Imperial and the AER are the latest failing in a flawed provincial regulatory system in which oil companies have been allowed to largely police themselves.

“We call that regulatory capture,” Lepine said. “We cannot rely on industry to self-monitor and that’s why we need stronger enforcement.”

Imperial declined to comment on regulatory issues.

Asked about Indigenous concerns around tailings management, Guest said Suncor works with the AER to satisfy regulatory conditions and engages with communities to address their concerns.

Ottawa set up a crown-Indigenous working group with nine communities in 2021 to consider the proposed effluent regulations, which would be similar to rules governing Canada’s metal and diamond mines.

Lepine said First Nations want to consider alternatives. After decades of tailings management being left to companies and the AER, they want the federal government to take a broader view of how tailings ponds will be reclaimed and who will pay for it.

Remediating oil sands mines could cost C$130 billion ($95 billion), according to a 2018 internal AER memo, though in an official estimate the regulator puts the cost around C$34 billion. A oil sands mine clean-up fund, which companies pay into to cover end-of-life obligations, held just $913 million in 2022.

The federal ministry Environment Canada said it is aware First Nations do not trust the system in place.

“The conversation will continue in our crown-Indigenous working group on the long-term management of these environmental liabilities that are tailing ponds,” spokeswoman Kaitlin Power said.

A federal government source with knowledge of the situation, who is not authorized to speak with media, said Environment Canada is very keen to support communities’ calls to take a step back on developing the regulations but time is running out as tailings ponds get closer to reaching capacity.

The effluent regulations could be an opportunity for Ottawa to introduce more aggressive rules around how companies treat tailings before the water is released, the source added.

“There’s an urgency to move but we’re not just going to impose government regulations,” the source said. “The trust was lacking anyway, this was always going to be challenging and (Kearl) makes it more challenging.”