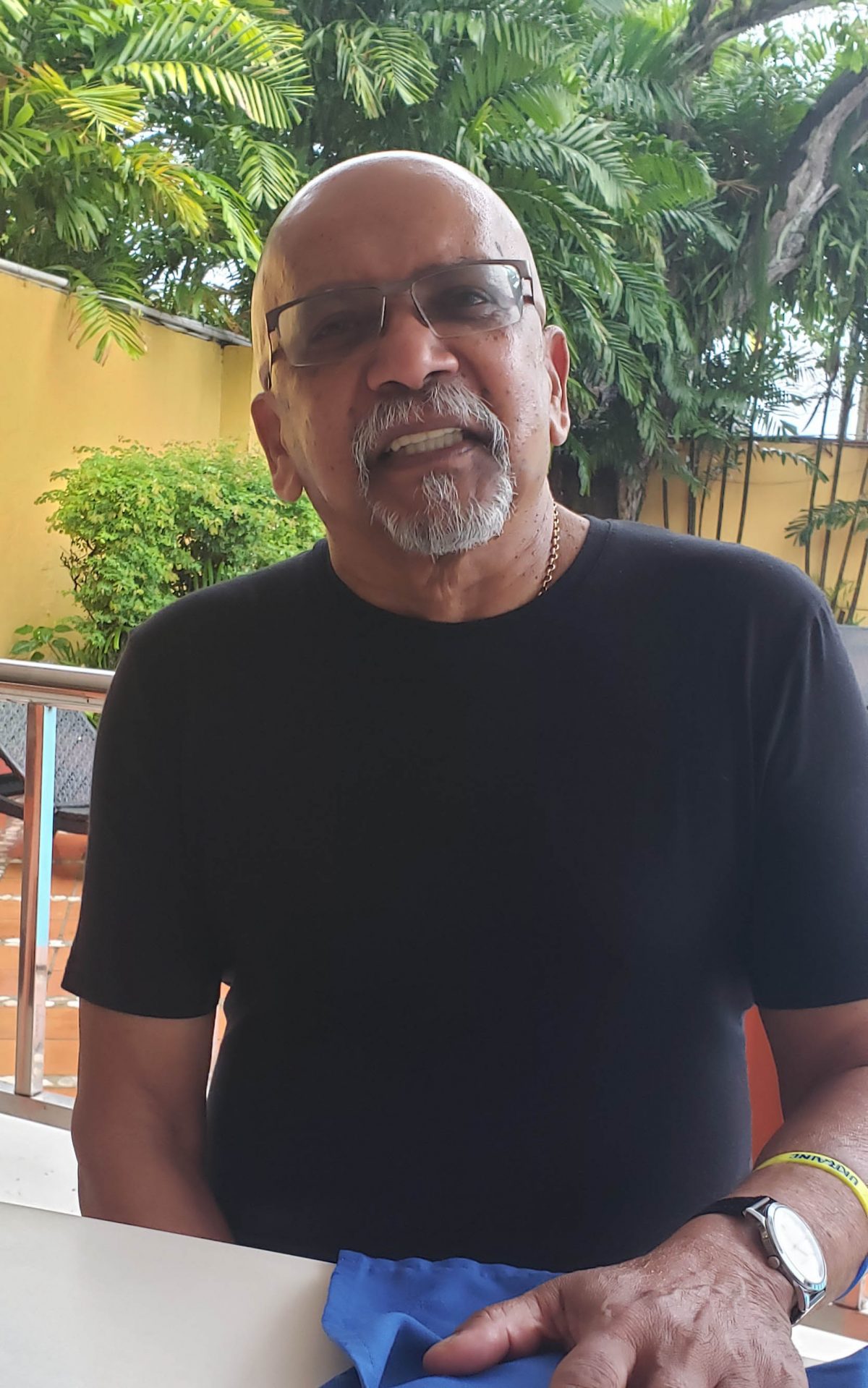

From a bookless home in Palmyra Village, East Canje, Berbice and growing up among cattle, historian and author Clem Seecharan dug deep into local and international repositories and has researched and authored over 18 books on cricket, the Guyanese and Caribbean way of life, all steeped in social and political history.

Seecharan, also a Professor Emeritus, recently won the inaugural non-fiction prize in the 2022 Guyana Prize for Literature for his work, Joe Solomon and the Spirit of Port Mourant.

“I love this country. I never look over my shoulders when I am writing about it. I have no sacred cows. I let the research do the work and I am a meticulous researcher,” Seecharan said. “When I do something, the thoroughness of the research is combined with all the great times I have had, the successes, the failures and the flaws. All those go into the work I do as a writer and have made me the person I am today.”

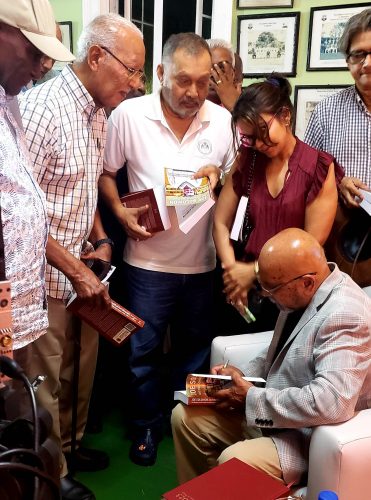

The author of over 18 publications, Seecharan noted that Joe Solomon and the Spirit of Port Mourant was the idea of author and poet Ian McDonald who worked with the late test cricketer Joe Solomon in the Sugar Producers Association and Bookers. Solomon also coached cricket on the plantations and sugar estates.

“Ian prodded me to write something about Joe and Port Mourant,” Seecharan, who lives in Warwickshire, England, told Stabroek Weekend in a recent interview.

Demerara Distillers Limited sponsored the award-winning book. Coinci-dentally, Solomon was himself a distiller and owned a distillery. The book was launched at the Georgetown Cricket Club, Bourda on April 20.

The research, he noted, required some corporate sponsorship to access the type of historical documents and

records of Guyana’s colonial history found only in London and other parts of Europe. “Most of the research was done in London. Newspapers have disappeared from the archives in Guyana or if you try to hold them they break up in your hands,” Seecharan noted.

He said that cricket cannot be separated from the social and political history of Port Mourant.

“VS Naipaul, who visited Port Mourant in 1962, said people there believed they were the best Guyanese. There was something in the air, the spirit of the place that produced not only cricketers but people in medicine, law and small businesses. There was something about the place that gave it a certain vibe,” he added.

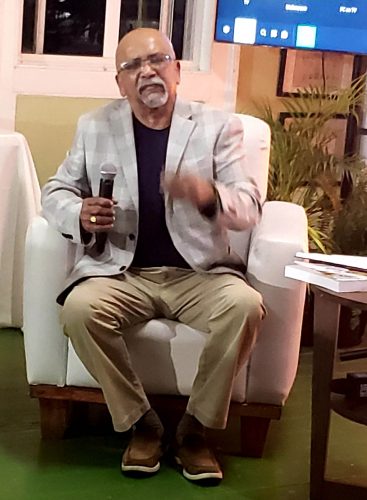

Seecharan is now working on the fourth volume of the Hand in Hand History of Cricket in Guyana. He has already published a first and second volume and the third volume is awaiting publication.

“The inspiration to write Cricket in Guyana also came from McDonald,” he revealed. “I listened to his viewpoint on radio and read his articles on cricket and sports in the Chronicle at the time. That was a major factor in my turnaround and me continuing with the PhD after a period of misbehaviour after completing my master’s degree. Ian continues to be a great source of information to me.”

The volumes are sponsored by the Hand in Hand Trust Corporation as part of its 150th anniversary legacy project.

“The year 2015 was also the 150th anniversary of the first first-class match ever played in the West Indies. It was played between Barbados and British Guiana in February 1865 and it nurtured West Indies cricket. The Hand in Hand company was founded in October of 1865,” he related. The first volume covers 1865 to 1897; the second, 1898 to 1914; the third, 1915 to the 1930s and the final one will cover the post-World War II period to Guyana’s independence.

“I don’t think anything else of this nature exists anywhere else in the world. The work is not just about scores and who made how many runs, cricket is integrated into the social and political history of British Guiana. It is Hand in Hand’s contribution to the history of a great game during the colonial period. Someone might decide to take up the period after independence,” Seecharan said.

Formative years

Born in Palmyra Village in 1950, from the time he could read, Seecharan read the daily newspapers. In the late 1950s he joined a well-stocked New Amsterdam Public Library.

“My parents were literate but they were not readers of books. Although I came from a bookless world, I became totally infatuated with the whole idea of words, reading and using words,” he said. “For me that is life. I can use standard English and I can do the same with Creolese but I’m not poetic like my friend Ian McDonald.”

As a child Seecharan read the newspapers daily as a source of information, because the environment in the early 1960s was politically charged. His father worked at the New Amsterdam Psychiatric Hospital and was also a cattle farmer.

“The newspaper, edited by Kit Nascimento who was anti-communist, was also very anti-Jagan and anti-PPP [People’s Progressive Party],” he recalled. “My parents, who voted for Jagan, subscribed to the Daily Chronicle newspaper which not many people did in those days. Uncon-sciously I was introduced as a little boy to the politics of Guyana, challenging political dogmas and challenging the sanctity of political views.”

When he joined the New Amsterdam Public Library, he was fascinated with the writings of Edgar Mittelholzer who hailed from New Amsterdam.

“I knew the house in Coburg Street where he was born. There was a plaque which read ‘From 1909 to 1965 Edgar Mittelholzer lived here’. They pulled down the house and nothing remains, not even the plaque. That is not important to a society like ours,” he lamented.

At that time Seecharan told himself, “If a man from my town could be publishing books in London, I can do it. From a very early age I could associate myself with Mittelholzer’s books and with a man who was born here. I even knew a few members of his family. This brought home to me the art of writing. I am not saying these things were presented to me when I was young but those seeds were planted in me then.”

Peter Kempadoo, who was also from Port Mourant, had by then written Guiana Boy (1960) and Old Thom’s Harvest (1965). These were published in London and Kempadoo also had an impact on Seecharran.

Apart from Mittelholzer and Kempadoo, Seecharan found that several authors from the Caribbean region were living, writing and publishing in London. Naipaul had already published several novels including The Middle Passage. He had visited Guyana to research for that publication.

Seecharan’s primary education was at Sheet Anchor Anglican School and his junior secondary was at Berbice Educational Institute where he successfully wrote several General Certificate of Education Ordinary Level subjects. He then went on to Queen’s College to write several subjects at the GCE Advanced Level.

“At Queen’s I was a maverick, an unconventional student,” he recalled. “I was doing history, geography and economics. Our teachers did not really give us much. Many times I did not show up for classes. I spent a lot of time at Freedom House reading things on Marxism. I got to know Dr Cheddi Jagan.”

An admirer of Jagan who he got to know personally, Seecharan said Jagan treated him like an adult even though he was a high school boy; “most of all he gave me not only an enthusiasm for learning but he enabled me to look at things from a critical perspective.”

In Georgetown, he accessed the British Council Library where he read periodicals like “The Listener”, “The Spectator”, and “The Weekly Guardian”. He also visited the United States Information Services Library and the National Library.

“I was in the whole world of learning by reading. The syllabus at QC was extremely boring. I had to make sure I passed the subjects I was taking because it was necessary to move forward,” he recalled. “My parents were paying for me to stay in Georgetown. Most of my teachers were not trained teachers and the syllabus was meant for English/British students primarily.”

Cricket

Though he has written extensively about cricket, Seecharan only played at the village level. “I was always a theoretician of the game. I practised with the guys but I was not as good as them. Berbice had a lot of outstanding county players and some played for Guyana. One of my cousins played for the West Indies,” he revealed.

The fascination and history of the game were all part of his education. “I was greatly influenced by the CLR James classic, Beyond the Boundary, which came out in 1963. I first saw it in the Public Library in New Amsterdam. I was the first person to read the book by the stamp. I didn’t understand all of it when I first read it. That book opened a whole new world to me,” he said.

Another book that influenced him was an old copy of Discovery of India by Jawaharal Nehru, the late Indian prime minister, who wrote it when he was in jail.

While he was still in high school, Seecharan acquired a habit of talking to people in the village about his newly-acquired knowledge. “People congregated around me in the village as though I was some politician. I had that enthusiasm for learning, but not the learning that was forced on us by the official curriculum and the exams we had to write. I wanted to know more, to analyse, to understand my own society and environment,” he said.

Seecharan visited Port Mourant, which was ten miles from where he lived, with an uncle to watch teams vying for the Davson Cup. Their team, Fort Canje (Mental Hospital) played against Albion, Skeldon, Rose Hall and other plantations. By then Port Mourant had already produced many doctors, lawyers, business people, educators.

Frank Worrell’s test team of the early 1960s, had Rohan Kanhai, the number 3 batsman; Basil Butcher, the number 4; and Joe Solomon the number six all from Port Mourant and its environs. “All these players, John Trim, the first test player, Ivan Madray, Alvin Kallicharran, the Etwaroos, all came from within three hundred yards of each other,” he related.

McMaster University

With the White Canada policy falling apart by the late 1960s, several students had gone to Canada to study. Among them was the brilliant Halvidar Singh who was among the first batch of graduates from the University of Guyana, and who had gone to McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario to pursue a doctorate of philosophy in physical chemistry.

Seecharan wanted to go too. He got into McMaster University. “Halvidar Singh hadn’t finished his PhD when I got there. We became friends and ended up sharing a place. At the time I paid the same fees as the Canadians. There were no disparities between local and foreign students,” he recalled. “I worked during the summer at the university as a cleaner on a student visa with a work permit. I was able to a great extent, support myself. At one point, one of my housemates was my friend Richard Van West Charles. About 300 students from the Caribbean were studying at the university during the period I was there.”

At university Seecharan continued his political discussions; “I ended up speaking at a few meetings. I was even filmed on the local television attacking American imperialism and what the Americans were doing in the Vietnam war.”

Misbehaving in the 80s

Having completed his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in history, Seecharan was admitted to the PhD programme at McMaster. “I wasn’t enjoying it at all. I had wanted to return to the Caribbean to research colonial Guyana. I wanted to do something on the history and politics of the Caribbean and the university didn’t have the expertise in that area,” he said.

He registered at the University of the West Indies St Augustine Campus but the fees required of foreign students were exorbitant. He returned to Guyana and so began his period of misbehaviour. “I drank with the guys all over the place. I had many female friends and no sense of responsibility. By then my father had done extremely well with the cattle business. I wasn’t working anywhere but spending some of his money. I had friends who were fairly well off too,” he recalled.

“Again, people thought I was a maverick. Here is this man with all this intellectual ability, with a bachelor’s and a master’s and had started a PhD tending cows. What was he doing drinking with the guys in the village? My parents were terribly embarrassed.”

Seecharan was in his late 20s by then. “… Guyana was in a terrible mess but it gave me the opportunity to travel all over the country and to meet all kinds of people. The other side of the period of my misbehaviour actually exposed me to the society in a way, if I hadn’t behaved in that way, I would not have connected or engaged with this society and its environment. It was a learning experience because now as a matured person I could ask important questions about the environment and society.”

In spite of his behaviour, Seecharan delved into the National Archives with all its problems and the National Library where he went through the Timehri journals, first published in 1882 and then intermittently until the 1960s. “They are one of the great journals by any international standard. I was also learning even though it wasn’t bringing in any material rewards. In a strange way it gave me a sense of recognition. I was always sharing my learning when I was drinking with the guys and women in the village.”

PhD

Even though the curriculum at McMaster had nothing on Caribbean and West Indian history, students were allowed to do term papers once approved by a tutor. “That allowed me to do some aspects about religion in Jamaica, some aspects of the Black Power movement and the trade union movement in Guyana. Although the courses did not address specifically Caribbean or West Indian issues, I was able to do term papers within the framework of those courses which took me into research and writing on the region. When I moved onto the PhD there was no supervisor in the field. That was the context in which I was admitted to UWI. There I started my thesis on East Indians in British Guiana after the end of indentureship,” he said.

Itching to get back into the world of academia, Seecharan wrote to Professor David Dabydeen, who had won the Commonwealth Poetry Prize in the early 80s and was teaching at the Centre for Caribbean Studies at the University of Warwick.

“David is an adventurer who always thinks there is a solution to a problem. The fees would have been enormous but he manoeuvred some things and got me registered as a part-time student so I was able to pay like 400 pounds sterling a year,” he said.

In London, Seecharan had access to the Public Record Office, British Library, Colonial Office Library, Royal Commonwealth Society Library, Colindale Library, as well as Oxford and Cambridge libraries. All the Guyana newspapers were found in one or more of those libraries.

“In my writing I had access to all these libraries and all Guyana’s newspapers including those of local political parties and the Advocate of the then Manpower Citizens Association and Booker’s News,” he recalled.

“A whole world I had been dreaming about opened up to me. It was almost as if I was going to the great Meccas I wanted to be in. I was in my early 30s, so I had the maturity.”

He integrated his experiences into his approach to writing; “In research you bring your own perspective to things. You can’t separate, even as a historian, writing from all the things that influence you.”

He was a PhD student when he met his wife. They have been married for almost four decades. “She is English but she had read all these West Indian novels, including Samuel Selvon whom she met,” he said.

Having completed his PhD, he found work with the then University of North London, now the London Metropolitan University, which had founded a Caribbean Studies programme. “No one wanted to take on the administrative side of things. I took it on and held that post for over 20 years,” he said. Seecharan retired in 2013 but from time to time goes back to lecture.

Since he retired he has been writing full time. His first book was Indo West Indian Cricket published by Hansib in 1988. Some of his other books include From Ranji to Rohan: Cricket and Indian Identity in Colonial Guyana (2009); “… Muscular Learning (2006), my first book on West Indian political and social history. It combines Black intellectual thoughts, the whole Black experience, Marcus Garvey’s world,” he said.