In this week’s edition of In Search of West Indies Cricket, Roger Seymour

recounts an interview with Reg Scarlett, the former West Indies off-spinner.

In the September 1981 issue of Playboy magazine, American author James Michener was the subject of its famous extended interview. In response to a question about unfinished projects, he recounted how he had spent several years working on a book about Mexico only to abandon it. At that moment, Michener had no idea where the manuscript was, and thus presumed that it had been lost forever. In November 1992, Michener simultaneously released his 21st historical fiction novel, Mexico and a non-fiction novella, My Lost Mexico. In the latter, he traced the genesis of the book, the research, the two years of writing, the abrupt abandonment, and packaging it to be sent to the Library of Congress. It never went. Thirty years later, a relative found the manuscript in cardboard boxes in an attic. Michener rewrote the book, delivering yet another international bestseller.

The story of the misplaced manuscript was a source of fascination and I sought to be extra careful with my jottings, notes and newspaper clippings. In August 1997, when Guyana hosted the Nortel West Indies Youth Cricket Tournament, I interviewed several people integral to West Indies cricket. Shortly afterwards, I moved and my notebooks, which also contained match notes, were misplaced and assumed lost forever. A few months ago, whilst rummaging through a box of old family photographs, I found a large worn envelope. Inside were the missing notebooks. Here is one of the ‘lost’ interviews.

On the morning of Tuesday, 26th August, I went to the Pegasus Hotel to interview Mike Findlay, former West Indies wicket-keeper and captain of the Combined Islands. At the time, Findlay was the Chairman of the Selectors and had agreed to the interview on the condition that the subject of selection was not broached. There, Findlay introduced me to Reg Scarlett, another former West Indies Test player, whom I had heard doing radio commentary on Shell Shield matches when Guyana visited Jamaica.

At the West Indies Cricket Board (WICB) Annual General Meeting three months prior in Georgetown, Guyana, Scarlett had been appointed WICB’s first Director of Coaching on a two-year contract. According to a WICB press release, Scarlett would be responsible for “the structuring and overall implementation of the WICB’s coaching development plan.”

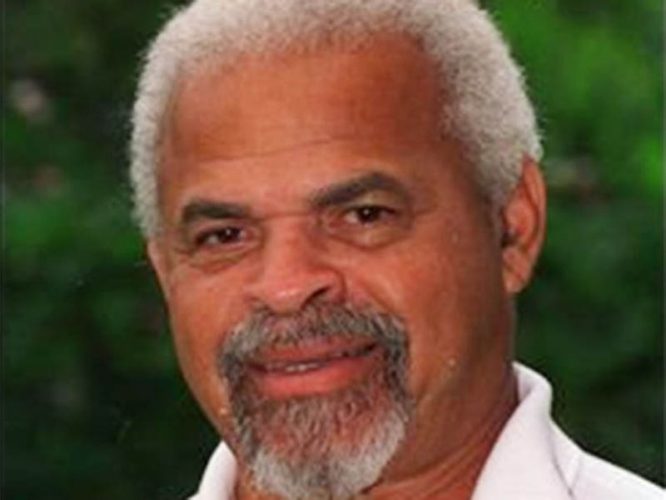

At Findlay’s suggestion, Scarlett readily agreed to a chat on “West Indies cricket”. The following evening I picked him up at 7:30 and we headed out for “Chinese food” as per Scarlett’s choice. A hulk of a man, very amicable, Scarlett was a natural conversationalist, who was a walking encyclopedia on West Indies cricket. Over the course of three hours, he traversed all manner of subjects.

Initially, Scarlett sketched a quick background of his cricketing life. As a student at Jamaica’s famous Wolmer’s High School, he was encouraged to join the school’s nets session one afternoon by Jackie Hendriks, the school’s wicket-keeper. The enormous turn his off-spin bowling extracted on the concrete pitch caught Hendriks off guard, and he was soon representing the school in the Sunlight Cup, Jamaica’s secondary school cricket competition. He chuckled as he recalled being summoned to the Principal’s Office one Monday morning, along with his squire behind the stumps, after he had rooted a rival school’s batting line-up with the stunning figures of six wickets for eight runs, “Of course, our groundsman had doctored the wicket.”

Along with Hendriks, he progressed to the Kingston Cricket Club at Sabina Park, and then made his Jamaican debut in 1952, and two years later, took eight wickets in two matches versus Len Hutton’s MCC side (bear in mind that there was little first-class cricket in the West Indies in those days). His Test career was limited to just three matches in the 1959-60 home series versus England, in which he took only two wickets and did nothing of note with the bat. With the emergence of Lance Gibbs, and little prospect of playing any further Test cricket, Scarlett moved to England with the intention of pursuing studies to become a school teacher. There, he said, a Jamaican housekeeper, questioned his career choice: “What’s this talk of you becoming a teacher? You’re a cricketer. Make your living as a cricketer.”

Scarlett noted that it was the conversation with the Jamaican woman which prodded him to pursue cricket as a livelihood. Initially, he played as a professional in Scotland for a few years before switching to the hard school of the Lancashire leagues where as the professional among a bunch of amateurs one was expected to do everything: coach, captain the team in some instances, motivate everyone, take wickets by the bunches and make runs every time. “Tough crowd up there. They know their cricket, you have to produce,” he said. He represented Ashton Cricket Club in the Central Lancashire League from 1962 to 1966, never revealing – too modest – what later research did. [In 1964, Ashton C C, whose history dates back to 1857, had its best season since 1940, finishing runners-up in the league, and winning the Wood Cup final. Chasing Heywood’s total of 102, Ashton were floundering at 42 for five, before Scarlett and fellow West Indian Ken Kelly put together a match winning partnership of 45. The following year, Ashton retained its hold on the prestigious Wood Cup trophy, to give the club the best two years in its long and storied history.] At this point he mentioned his long friendship with Guyanese fast bowler Charlie Stayers, who played for Enfield Cricket Club in the Lancashire Leagues. In the off seasons, after attaining a cricket coaching certificate, he plied his trade at various high schools.

After 15 years in England, Scarlett went home to oversee the Jamaica Cricket Association Youth Development Programme. Four years later, he returned to England, where he became the driving force and coach of Haringey Cricket College located around the corner from the home of the famous Tottenham Hotspurs Football Club, in one of the most depressed inner city neighbourhoods in the UK. The college, the first of its kind in the UK, was set up shortly after the infamous Brixton riots of 1981, as a charity focused on unemployed youth, and aimed to produce “good cricketers and good citizens”. It placed heavy emphasis on vocational training.

Scarlett, through his network of contacts, was able to secure matches for the college, which competed under the title ‘London County’ (a nod no doubt to W G Grace’s old team), against county second XIs. In his fifties by that time, Scarlett led the team on the field for tactical reasons, but left the youth to their own survival devices in the tough world of cricket. It was from the Haringey Cricket College that the WICB recruited him to develop the Caribbean coaching programme. However, the story began long before that.

“In 1984, I began writing letters to the West Indies Cricket Board on the need to set up a coaching programme for youth cricketers,” Scarlett said. “Yes, we were winning at the time. We were beating everyone in sight. We had just swept the English five nil in England. I emphasised the need to build on the momentum of the winning to attract more players to the game. I never got any replies to my letters.

“The board probably assumed that the winning would continue forever. We had an abundance of talent, enough fast bowlers for two teams, and we were incredibly lucky. So many times games would swing in our favour that we had no right winning, and the streak just continued. I wrote more letters and got no response.

“Here’s what I foresaw happening. The talent pool was starting to dry up, as more and more kids were watching basketball, and wanted to be like Michael Jordan. One day, the luck was going to run out too. Then what? The losing will start, teams are starting to make inroads. Australia has beaten us twice, at home [2 -1,1995] and abroad [3 -2, 1996-97], and England held us to a draw in England [2 -2, 1995]. Pakistan will probably beat us later this year when we visit them [Pakistan won 3- 0].”

Scarlett paused, put down his fork, as I scribbled madly in my notebook. I looked up, no doubt a quizzical expression on my face, and he resumed.

“Hence, the need for an academy to keep the supply of players and the standard of the game at a high level. Here’s the real problem, we are about 15 years late, this programme should have started a long time ago. Australia, England and South Africa have been waiting a long time for us to weaken. They have been building their programmes for years, in fact, they are light years ahead of us in every area, especially in the use of technology. We are going to take a beating for years to come.”

“How many, you think?” I interjected, hoping to hear five or six. Scarlett, seeing my concern, smiled, “Fifteen, maybe twenty years, who knows?

“A solid Test cricketer is hard to produce. An academy like we are working on might give you one or two real Test cricketers every three years. We have to start from the bottom and build the interest and cultivate the talent. We need to begin with the six year olds, kiddie cricket. This is not an overnight process. This will take years to develop and maintain. We have to train coaches, we have to go everywhere in the Caribbean and look for talent. We will go to Anguilla too, I understand they play cricket too. [In 2003, Anguilla’s first Test cricketer, Omari Banks, scored 47 not out as the West Indies completed the highest successful run chase in Test history, 418 versus Australia at Antigua.]

“Then we have to develop the talent. It’s just not a matter of natural ability. The players have to understand the game in its entirety. They also have to be physically and mentally fit to play five days of Test cricket. Test cricket is a tough game. The programme has to be carefully planned, bearing in mind you don’t want to overload the players during the learning curve. Take for instance, the leg-spinner training camp held recently in Jamaica and conducted by Intikab [Alam, the former Pakistan captain]. The clinic lasted too long [one week]. It’s only so much a young player can absorb at a time, and then he has to go back home, and practice it over and over, and then incorporate it into his game. We also have to teach the players about our history. Do you know most younger players have little or no knowledge of the history of West Indies cricket?

“If I were to ask you to make a video of who you think best represents what a West Indies batsman should like, who would you choose? He must have all the shots in the book and be able to play them all with style, grace, flair, and power.”

“Lawrence Rowe,” I replied.

“No, lacking in some areas,” he countered.

I pondered for a moment or two, silently going over the possible short list. Richards? No. Sobers? Too obvious, he must have someone else in mind.

“Kallicharran,” I finally said, “must be Kalli, he had all the tools.”

“No, I’ll save you the agony,” Scarlett said. “Bacchus. Faoud Bacchus, your Bacchus. No one else comes close. He had everything. Style. Flair. Grace. He could do everything with the bat. It’s a pity he never fulfilled all that promise.”

That was high praise, coming from one who had seen it all; the tail end of Headley, played with and against the three W’s in their heydays; Sobers, Kanhai, Lloyd and Viv.

“Yes, Bacchus is the most complete West Indies batsman I have seen,” he said.

“Not Garry?” I queried.

“Garry had a piece or two missing. Let me tell you a Garry story. One night, I was leaving a nightclub in London, it was late, and I heard a voice say, ‘Reg? What you doing here?’ I turned around and it was Garry. I hadn’t seen Garry in a while. It was great as usual to see him. He suggested we go to another club for a drink and catch up on the old times from our Lancashire League days. Garry is a bit of an insomniac, you know. It turned into an all-nighter. Garry persuaded me to go back to the Clarendon Court Hotel where the West Indies were staying. We settled down at the bar, drank and chatted until about 9 o’clock, before Garry went upstairs showered and headed over to Lord’s to resume batting on the second day [August, 23rd] of the Third Test, 1973. Sobers made 150 not out [after resuming on 31], having not slept a wink all night.”

Scarlett laughed heartily, “Yes, Garry is different to all of us. Speaking of drinking, I can’t tell you how many times I have gotten drunk on Guinness. Whenever I meet an Irishman in a bar and he finds out I’m from the West Indies, he immediately reminds me of the time Ireland dismissed the West Indies for 25 [on a wet wicket during the 1969 Tour of England]. I have to hear it over and over again. No problem, the Guinness just keeps flowing.”

“Ever heard of Sam Ramsamy?” he asked, jumping to another topic.

“Isn’t he that South African fellow that was always campaigning against sporting contact with South Africa during apartheid?” I asked,

“Yes, that’s him. I worked with him and his organisation, SAN-ROC [South Africa Non Racial Olympic Committee]. Sam was based in London and I helped compile the UN Register of Sports Contacts with South Africa [initiated in 1980 by the UN Special Committee against Apartheid] which was a list of sportsmen who had participated in sports events in South Africa. We would listen to the shortwave broadcast of sports events and record the names of participating players. I listened to all the cricket matches,” Scarlett revealed.

“Sounds like you were a modern-day Scarlett Pimpernel,” I quipped.

Scarlett laughed heartily: “Not really, but I do own a company which supplies cricket equipment to schools and other organisations, mainly bats, which is registered as ‘The Scarlett Pimpernel’.

“Speaking of listening to broadcasts, I listen to cricket from all over the world regardless of who is playing who. I normally tune in on the BBC channels and when the broadcasts switch to Urdu in Pakistan, I will still listen and try to figure out the score.

“You know, I can’t pass a game of cricket anywhere. I have to stop and look, even if it is for one over. You never know what you might see.”

“Do you see a bright future for the game of cricket?” I asked.

“I have a sign which hangs behind my desk,” he replied. “It reads,’Cricket is a dying game.’ At the bottom, it says, The Times, 1877.”

Postscript

The Haringey Cricket Academy closed in 2000 due to cutbacks on government funding. Among its outstanding graduates were former England all-rounder and Gloucestershire captain Mark Alleyne and Warwickshire wicket keeper Keith Piper. In the words of England’s first Black Test cricketer, Roland Butcher, who Scarlett invited to be a mentor at the school, “The college was ahead of its time. Cricket and life skills are very important. Quite often the emphasis is too much on one or the other, but both are really important, because after sport, there is life.”

The Shell Cricket Academy opened on the campus of the St George’s University in Grenada in May, 2001, under the direction of Dr Rudi Webster, supported by Scarlett. The institution closed in 2005 when the West Indies Cricket Board was unable to attract funding.

The last time I saw Scarlett was the evening after Roy Fredericks’ funeral in September, 2000. He passed away in England on 14th August, 2019, one day before his 85th birthday. In early February, 2020, Reg Scarlett’s ashes were scattered at the northern end of Sabina Park by his widow, Trish, and former schoolmate, Jackie Hendriks. It was a symbolic end to his final innings, where he had married Trish on 1st February, 1991.