By Nigel Westmaas

Introduction

An important turning point in the fight against the British imperial plantation system and global chattel slavery was the uprising in Guyana 200 years ago in August 1823.This event displayed incredible daring, courage, the effectiveness of group action and the capacity of the enslaved to shape their own fate by attacking the institutional and physical embodiment of their servitude.

It is impossible to overstate the significance of the massive revolt in Guyana sandwiched as it was between two other momentous “Caricom” slave rebellions, Barbados (Bussa) in 1816, and the Jamaica insurrection in 1831. Together, all three revolts helped to undermine the political, economic, and moral foundations of the British imperial plantation system and, consequently, the existence of worldwide chattel slavery.

The significance of 1823 would have been overshadowed by other slave rebellions in Guyana and the Americas or lost to history altogether were it not for the late historian Viotti da Costa’s outstanding book Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood which is the most thorough account of the revolt to date in terms of context setting, evaluation, and sheer sweep of detail.

Da Costa’s emphasis on the agency of the enslaved is particularly important, as it challenges the notion that history is predetermined by impersonal forces or that individuals are mere pawns in historical processes. Instead, Da Costa highlights how the actions of the enslaved were critical in shaping the course of history, and how their resistance played a crucial role in bringing about the end of slavery in the British colonial domain.

Context

Everywhere in the Caribbean and the Americas slave resistance was endemic and extensive. Path breaking new research by historian David Alston challenges previous assumptions about the size and scope of maroon communities in Guyana and their impact on the plantation economy from the significant maroon resistance in 1795 in Demerara all the way to the official end of slavery in 1834. In Alston’s words, “maroon communities were larger, more resilient and more enduring than has been recognized.” A stark statistic amplifies the significance of those communities as maroon production in the “borderlands” was recorded as producing so much rice that one European officer cited by Alston “estimated that the rice already destroyed had been enough to support 700 enslaved people for a year.” In addition to the maroon uprisings, smaller slave rebellions occurred in Guyana in 1807, 1814, and 1818, but they have received less attention in historical accounts.

In Britain criticism of slavery had decreased after the slave trade was outlawed in 1807 (sort of a “okay, we accomplished our aim” kind of mood). In Guyana planters called a meeting in November 1811 to deal with “ruin”, and reportedly, “tempers rose, acrimony filled the air.”

The widespread unrest in Guyana in the 1820s was also fueled by rumours of emancipation coming from London, particularly the agitation of British abolitionists Wilberforce, Buxton, and others in the House of Commons. Slaves spoke of laws emanating from England, the King and general “rights”.

But detailed discussion of 1823’s origins must repose in the scene of the large crime of slavery. The immense disruption of black lives, the daily violence, the whippings, branding, family separations, the rapes, the individual and collective brutality, the denial of cultural and human rights, and general dehumanization occurred in Guyana and everywhere in the hemisphere where chattel slavery was practiced.

The Demerara slave rebellion was preceded by Governor Bentinck’s restrictions on enslaved people’s entry into chapels in Guyana, which was a significant factor that contributed to the timing and intensity of the uprising. Prior to these limitations, slaves could venture into chapels. This allows for a segue into the role of religion in the uprising. There are perils in depicting the Rev John Smith and the London Missionary Society as ‘originators” of the rebellion as against the reality of the enslaved acting in their own interest and seeking to free themselves. While religion was a major factor in the rebellion there was selective and tactical use of religion (Bible) by the enslaved. “The British missionary enterprise disseminated the Bible across the empire with often unintended consequences. The reception of the Protestant Scriptures among colonial subjects was anything but passive. Readers and listeners from among the enslaved congregations appropriated scriptural texts in their own distinctive, even subversive ways.”

In short, history from below, the agency of the enslaved, overrides the narrative that John Smith led the revolt thus assigning agency to a white leader over a supposedly ignorant enslaved population. In addition, as Da Costa reports, Smith’s racism is exemplified by one of many incidents, where he referred to some “half naked slave women who were washing clothes in the river to orangoutangs.” However, on account of the contradictions between the church’s stance on plantation slavery and the authorities in Demerara and England, we cannot ignore the significant role played by Smith.

Course of the Revolt- Organisation, Leadership & Outcome

But what about the revolt itself? To briefly recount, on August 18, 1823, thousands of the enslaved in Guyana rose up and attempted to completely uproot the system of plantation slavery that existed since the 1600s in the colony.

But what about the revolt itself? To briefly recount, on August 18, 1823, thousands of the enslaved in Guyana rose up and attempted to completely uproot the system of plantation slavery that existed since the 1600s in the colony.

Da Costa’s evocative paragraph captures the essence of the first stirring of the revolt:

“The rebellion started at Success and quickly spread to neighbouring plantations. Beginning around six in the evening, the sound of shell-horns and drums, and continuing through the night, nine to twelve thousand slaves from about sixty East Coast plantations surrounded the main houses, put overseers and managers in the stocks, and seized their arms and ammunition. When they met resistance they used force. Years of frustration and repression were suddenly released. For a short time slaves turned the world upside down. Slaves became masters and masters slaves.”

The general pattern of the uprising was like elsewhere in the Americas, immediate attacks on plantations and seizure of weapons, detaining officials, and owners. The leadership was inspired by Quamina and his son, the 6-foot, 2-inch Jack Gladstone. It had been months in preparation – led by whispers of freedom and events in the imperial centre that controlled the country. As Da Costa intimated, “no one could tell when the idea of an “uprising…” was formed among the enslaved. Gal Beckerman in the book The Quiet Before avers that “change – the kind that topples social norms and uproots orthodoxies – happens slowly at first. People don’t just cut off the King’s head. For years and even decades they gossip about him, imagine him naked and ridiculous, demote him from deity to fallible mortal (with a head, which can be cut).”

This also requires listening to internal deliberations among the enslaved and the importance of the political agency or use of ‘rumour’ on the part of the enslaved, what Klooster calls “ubiquitous rumour” throughout the rebellions and revolutionary uprisings of the enslaved in the Americas and the Caribbean.

The presence of the Haitian revolution in the calculation of the enslaved in Demerara should not be discounted. It is very likely that Quamina and Gladstone, as well as other rebels, would have been aware of the “common wind” – a reference to the informal networks and interconnections among the enslaved – of the Haitian

revolution and its impact, both economically and inspirationally. Although Da Costa notes that no reference to the Haitian revolution was recorded among the rebels, it is highly improbable that the leaders of the revolt would not have heard of the events that took place in Haiti just twenty years prior. The fact that Haiti was in the news is clearly evident in the testimony during the trial of an overseer, Van Woorst, who quoted Rev. Smith as saying, “the slaves would never be better situated until something like what occurred in St. Domingue should take place here.”

Other factors were fortuitous for a slave rebellion on the scale of 1823. Some enslaved persons were allowed to travel to Georgetown to the market for instance, either on their own behalf or on behalf of plantation masters – which allowed them to communicate in the marketplace. In this way, ideas, plots, and open rebellion were contemplated.

Another possibility is the fact that enslaved people were often bought and sold from plantation to plantation allowing for some sharing of experience and knowledge of the rhythm of plantation experience in far away plantations.

At a more granular level, the leadership of the uprising assigned the enslaved from Rome and Peter(sic) Hall to alert the maroons about the plot. In addition, the Gladstone plan was to position a leader on each estate responsible for coordinating and acting to rouse the enslaved on their estate at the appointed time. All levels of occupation were involved in the revolt including artisans, boatmen, field labourers, teachers (catechists) and house servants.

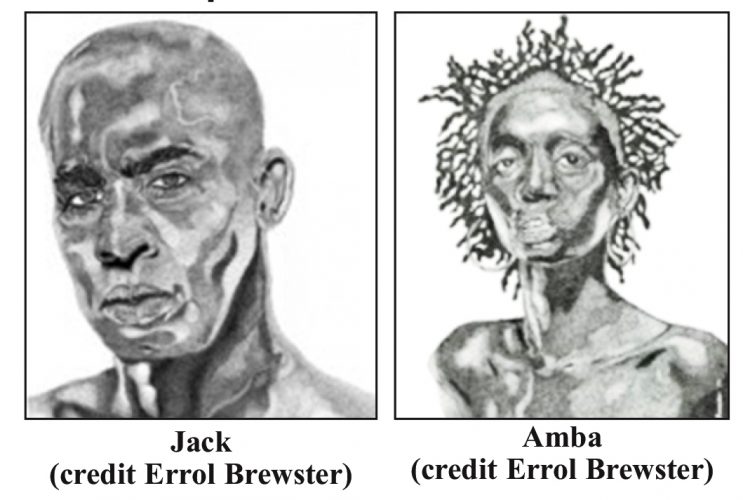

The largely peaceful uprising (in so far as the managers and plantation owners were concerned) was reflective of the participation of enslaved women. The most famous and feared woman leader of the revolt was Amba of Enterprise estate who openly walked around with a gun.

For days, the pitched battles between the enslaved and the colonial state continued. The excitement of the early success inspired statements like, “Niger (sic) make buckra run today”.

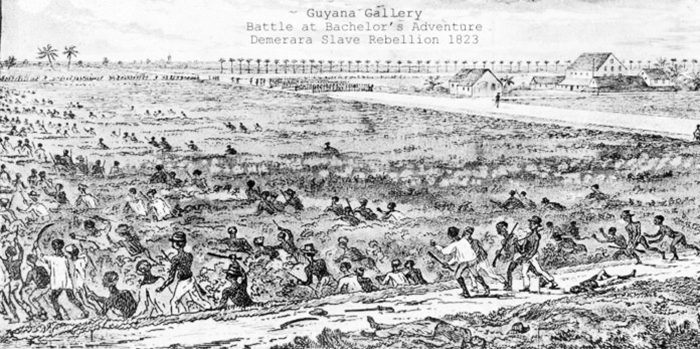

The massacre at Batchelor’s Adventure turned the tide of the slave rebellion. Col Leahy (a veteran of the Napoleonic wars), much like later military repressors, was zealous in his barbarism and this led to the death of 200 plus enslaved at just this location.

Quamina was eventually sidelined and killed in September 1823 as McGowan notes, “by an Amerindian in an expedition of militia men and Amerindians sent by the government and planters to capture fugitives”.

Quamina’s body “was dragged to the front of Plantation Success, bound with chains and hung between two trees as a warning of the fate awaiting prospective rebels. For months it remained there, swinging in the breeze, and becoming shriveled. According to an English resident, “a colony of wasps had actually built a nest in the cavity of the stomach and were flying in and out of the jaws which hung frightfully open.”

For his part, Jack Gladstone remained at large until he and his wife were captured at Chateau Margo, reportedly after a three-hour standoff in early September. Gladstone was spared the death penalty after his trial. Since Gladstone was massively popular and this act of amnesty might have been for tactical reasons and in any event during the trial Gladstone had implicated Smith, which was important for Smith’s prosecutors. Gladstone was eventually banished to St. Lucia. In all, 72 slaves were tried. 51 condemned and 33 executed.

The huge slave revolt of 1823 did have a direct impact on the deliberations and debate in England with Buxton and Wilberforce etc. Even in “defeat” the revolt sent a clear message across the region that nothing would stop the enslaved in fighting for freedom. Indeed, as indicated another huge slave revolt occurred just eight years later in 1831 in Jamaica.

Social forgetting and the Consequences of 1823 for the present

How should the nation commemorate the momentous event of the 1823 Demerara revolt, 200 years later? And in what ways does it matter for Guyanese historiography and memory of the present society?

The 1823 Demerara revolt holds great historical and cultural importance for contemporary Guyana, and it is essential to acknowledge and commemorate this event for several compelling reasons. First and foremost, the revolt serves as a powerful reminder of the intergenerational trauma that African Guyanese communities have endured as a result of colonialism and slavery. This trauma has had long-lasting effects on individuals and entire communities, and it is crucial to recognize and address it through public education and cultural practices.

Additionally, there is a contemporary erasure of black suffering and the black past in Guyana, which needs to be addressed through increased public education about events such as the 1823 revolt. It is essential to overcome cynicism about history by recognizing the importance of events like the 1823 Demerara revolt in shaping modern-day Guyana.

As a nation, we have a duty to provide proper recognition to individuals like Jack Gladstone in Guyanese historiography, at the same level as national heroes like Kofi. The achievements of Gladstone and Quamina in leading the 1823 revolt should be given greater prominence through public education, monuments, and other forms of commemoration. While a street has been named after Quamina and a few monuments devoted to the 1823 revolt exist, more needs to be done to ensure that this event is not relegated to just one day in a year with empty, recycled platitudes. Instead, ongoing public education and substantive appreciation should be promoted to ensure that the significance of the 1823 Demerara revolt is properly recognized and remembered.

Recognizing major events in our history publicly and institutionally is crucial. One effective way to do this is by minting commemorative coins to mark significant anniversaries, such as the 200th anniversary of the colossal slave revolt in Guyana. However, it is even more crucial to allocate resources towards educating the public about important events from all ethnic groups in the country. This requires a national effort to celebrate our diverse history and culture, motivated by a shared desire rather than a mandatory requirement.

Artistic representations of historical events, such as Errol Brewster’s depictions of Amba and Jack Gladstone in Thomas Harding’s book, White Debt, are essential for retracing these events through the imagination. They allow us to understand the significance of the slave revolt in Guyana and its place in the antislavery resistance movement in the Caribbean and Americas.

Finally, every university student and Guyanese parliamentarian should have institutional facilities to study the content and significance of the massive 1823 revolt on Guyana, the region, and the world. Pivotal texts such as Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood, among others, should be accessible to all who wish to understand the history of their country.