Achilles, in Greek mythology, was the son of the mortal Peleus, King of the Myrmidons, and the Nereid, or sea nymph, Thetis. Achilles was the bravest, handsomest, and greatest warrior of the army of Agamemnon in the Trojan War. According to Homer, Achilles was brought up by his mother at Phthia with his inseparable companion Patroclus. Another non-Homeric episode relates that Thetis dipped Achilles as a child in the waters of the River Styx, by which means he became invulnerable, except for the part of his heel by which she held him – the proverbial “Achilles’ heel.”

– Excerpted from the Encyclopedia Britannica

If younger cricket fans in the West Indies customarily accuse the older generation of heaping mythological dimensions on the Glory Days of the 1980s, their skepticism can be easily forgiven since, unfortunately, they have come of age in an era of incessant losing. The winning percentage during that epoch was 51.30, an unprecedented number, (46.27 percent in away matches [31 in 67 Tests] and 58.33 percent [28/48] at home), off the charts of reality, reflecting an unmatched level of dominance. However, like Achilles, the All Conquering West Indies, apart from the few occasions where they fell on their own swords, were susceptible to one vulnerability.

India 1987/1988

Sunday, 8th November, 1987; Calcutta, India; the Fourth ICC World Cup Final – Australia vs England; Australia won the toss and elected to bat first. It was the first World Cup final not played at Lord’s, it was also the first without the formidable West Indies, several of whom were present to witness the spectacle. Drawn in Group B with England, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, the West Indies split their six first round matches, inclusive of two heart rendering last over losses to England and Pakistan, and failed to qualify for the semi-finals. On the eve of an arduous tour of India, they were relegated to the unaccustomed status of spectator at the final. It was a bittersweet moment.

It was a critical tour for the West Indies. Viv Richards was at the helm of a team in transition, crucial parts were missing. All three of the fast bowlers with over 200 Test wickets were absent. Michael Holding and Joel Garner had retired from Test cricket, and Malcolm Marshall had opted for a break from the game. ‘Mr Reliable’ Larry Gomes, the dependable middle-order batsman also walked off into the sunset a few months prior. Gordon Greenidge, the long-serving opener, having missed the Reliance World Cup due to knee surgery, had returned for his third Indian sojourn. The remodelled team, which did not lack experience or talent, included the likes of Greenidge’s partner, Desmond Haynes, wicketkeeper/batsman Jeff Dujon, middle-order batsmen Richie Richardson and Gus Logie, fast bowlers Winston Davis and the Jamaican duo of Courtney Walsh and Patrick Patterson. Guyanese allrounders Roger Harper, the new vice captain, and Carl Hooper, the exciting young prospect on his first tour, were the focus of the future.

The tour encompassed a packed itinerary, inclusive of five Tests with frequent and long travel. Coming on the heels of the World Cup, in which the co-hosts India and Pakistan were both eliminated in the semi-finals, the Indian Cricket Board anticipated poor attendances at the Tests. At the last minute, the itinerary was altered, the Second Test scheduled for Kanpur was cancelled, and two more One Day Internationals (ODIs) were added to the five already slated, a decision that the West Indies were not too happy with, but agreed to, nonetheless.

November 15, 16, 17, at Hyderabad. The match against Hyderabad, the Ranji Trophy Champions was abandoned without a ball bowled, as a cyclone swept across southern India just prior to the match, causing devastating damage and leaving several dead in its wake. It was the first occasion on a West Indies tour to India that an entire match was lost to the weather.

November 21, 22, 23, at Chandigarh, Northwest India, in the foothills of the Shivalik Range of the Himalayas, the West Indies encountered India’s Under-25 XI. It was the only first-class match before the start of the Test series, and the young Indians exposed to international competition were anxious to show their true mettle to the selection panel. The Under-25s were led by wicketkeeper batsman Chandrakant Pandit, who made his Test debut the previous summer in England, and subsequently played two more Tests against the visiting Australians in the fall, chosen in all three as a middle-order batsman. Other players included Carlton Saldanha, a former India Under-19 player and the leading run scorer in the the 1986/87 Ranji Trophy with 782 at an average of more than 71; Krishnan Pillai, a solid batsman for the dominant Delhi side of the 1980s; and the promising batsman Sanjay Mandrekar, the son of former Indian Test cricketer, Vijay Mandrekar, of whom much is expected. Narendra Hirwani, a 19-year-old spin bowler, who had previously bagged 23 wickets in an Under-19 three Tests series versus Australia, also made the final cut.

Richards won the toss and elected to bat. Following the early losses of Phil Simmons and Richardson, Greenidge and Richards plundered the attack, to the tune of 303 runs in 203 minutes. At tea time, the West Indies were 331 for two, as Greenidge retired out for 174. West Indies’ total of 550, included scores of 138 (retired hurt) from Richards, 50 from number ten, Walsh and 47 from Clyde Butts.

The overawed Under-25s were soon reduced to 73 for seven, before numbers eight and nine in the batting order, S K Sharma and Jaspal Singh, launched a fearless counter attack, slamming sixes and fours, in a similar vein to Greenidge and Richards in the West Indian innings. The spinners Butts, Harper and Richards were the focus of the whirlwind eighth wicket partnership which produced 135 runs in 70 minutes. Despite Sharma’s 76 and Singh’s 70, the Under-25s were dismissed for 228, conceding a lead of 222. Richards forsook the follow-on and opted for batting practice on the final day, and the West Indies cruised to 237 for six before declaring, with Phil Simmons (72), Dujon (42 not out), Richardson (37), and Greenidge (37), the leading run scorers. The match ended in a draw as the Under-25s reached 41 for one. The highlight of the day was that all six of the West Indies wickets fell to the young leg spinner Hirwani who delivered an unchanged spell of 30 overs, yielding figures of 30 -7 – 100 – 6. Simmons, Richardson and Butts were clean bowled by googlies.

When the Indian Test squad was announced the names of Sanjay Mandrekar and Narendra Hirwani were included. Who was this mystery spinner? Hirwani hailed from Gorakhpur in the state of Uttar Pradesh, near the foothills of the Himalayas, where his father owned a brick-making business. One night Hirwani had a dream in which he was bowling for India. Passionate about cricket he decided to pursue his dream. With his father’s blessing, and a little money, the pudgy 15-year-old set off for Indore, the largest city in the state of Madhya Pradesh, in central India. He had represented Uttar Pradesh Under-15s in the zonal Under-15 at Indore, and enthralled by the beauty of the city and the fact that Hindi was the spoken language, the only language he knew, he was determined to make it his new home. He rode in the general compartment on the long train journey, a green metal box with his possessions under one arm, his bedding tucked under the other.

In Indore, Hirwani headed to the Cricket Club of India (CCI) ground, where his eventual guru, Sanjay Jagdale, a Ranji Trophy player was ready to dismiss him on sight when he observed his excessive weight. He pleaded his case and Jagdale relented.

Hirwani was dogged in pursuit of his dream. He lost 25 kilos over three and half months, and trained all the time. There was no structured programme per se, but Hirwani ran ten to fifteen kilometres daily at 4.00 am, and then headed for the gym to execute Jagdale’s weight-lifting exercises. After the gym he bowled at a single stump for two hours. When club practice began at 2:00 pm, he bowled from the start until dark, aiming to fulfil his goal of bowling one hundred overs a day.

It was a lonely pursuit for Hirwani, to master the art of leg spin bowling, the most complicated aspect of cricket’s varied crafts. Hirwani had unconsciously been turning it ‘the wrong way’ ever since he was eight or nine years old, bowling the old cork ball which always seemed to be in his possession. Alongside his guru, Jagdale, he studied the how and the why, deciphering the physical and psychological intricacies of the leg spinner’s repertoire: the leg spin, the top spin, the googly or the wrong’un, and the flipper. The key to each delivery lies in the angle of the wrist at the moment the ball is released, an exercise in perfection that can only be met with hundreds and hundreds of hours of practice. There are so many parts to a bowler’s action, that the moment something goes awry, it can fall to pieces. None more so than that of a leg spinner, who, once he loses the ability to flight the ball, or pitch it in the right spot, or spin it hard, he then becomes fodder for any good batsman. Mastering the art of leg spin bowling requires the discipline and perseverance of a monk. Hirwani, the dream chaser was the perfect candidate.

At the age of 16, Hirwani represented Madhya Pradesh in the Under-22 Final, where his 12 wickets propelled his adopted state to their first lien on the trophy. His performance encouraged former India Test cricketer Ashok Mankad, then the Ranji Trophy coach to select him, despite much protestations from several quarters. Hirwani’s five-wicket haul on debut versus Rajasthan, quietly ended the furore. The next year, he was selected to represent Central Zone in the Duleep Trophy competition. A month past his 19th birthday, he calmly received the news that he was selected for India’s Test squad for the series versus the mighty West Indies.

At Delhi, November 25, 26, 27, 29. First Test. Hirwani later recalled, “Suddenly I was sharing a dressing-room with players who had been my childhood heroes, whose posters I had posted on the walls of my room. Here I was, in the same team as them. Just imagine – Kapil Dev, Srikkanth, Ravi Shastri, Mohinder Amarnath. People may not be able to comprehend how much in awe I was.” Mandrekar, his Under-25 team mate made his debut, as Hirwani watched the West Indies win by five wickets. Following low scoring first innings totals by both sides, Richards played a masterful unbeaten knock of 109 not out, as the West Indies recovered from 111 for four to get the required 276.

In December, the West Indies continued their punishing itinerary. At Pune, the match versus North Zone, the Duleep Trophy Champions was a drawn high-scoring affair. The First ODI at Nagpur resulted in a WI victory by 10 runs. The Second Test at Bombay was a rain-affected draw with the visitors enjoying the upper hand. At Visakhapatnam, the President’s XI were defeated by an innings. At Gauhati, India fell 52 runs short in the Second ODI. At Calcutta, the Third Test was drawn, as both sides posted over 500 in their first innings.

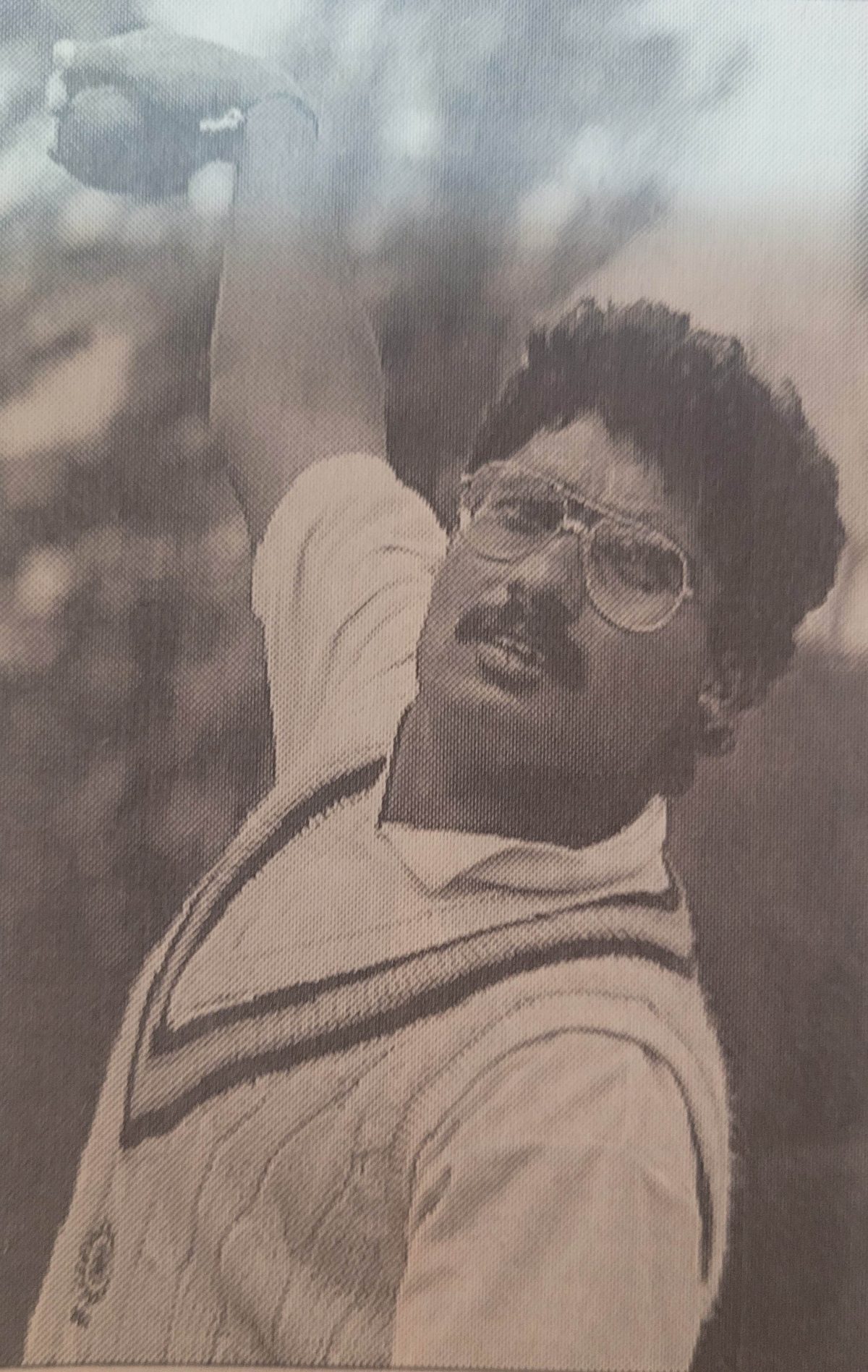

Hirwani recalled the moment his dream was realised. “We were going to Chennai from Mumbai for the final Test [January 1988], by which time Ravi Shastri had been named captain because Dilip Vengsarkar was injured. We were climbing the steps to board the aircraft when Ravi bhai tapped me on my shoulder and said ‘you are playing.’ The timing was great because I had enough notice that I would be playing. It helped calm my nerves and prepare better.”

At Madras (now Chennai), January 11, 12, 14, 15. Fourth Test. India’s first victory over the West Indies in 15 Tests was marked by one of the most astonishing debut performances in the history of Test cricket. Hirwani, one of three Indian players getting their Test cap, equalled Australian Bob Massie’s feat of taking 16 wickets in his first Test match, as the West Indies lost by 255 runs with a day and a session to spare. Hirwani’s match figures read; 18.3 – 3 – 61 – 8, and 15.2 – 3 – 75 – 8, for a combined total of 16 for 136, one run better than Massie’s 16 for 137.

The pitch was dry and dusty, ideal conditions for sharp spin for those who could exploit it. West Indies Tour Manager, Jackie Hendriks addressed it as a ‘mockery’, described it as “the worst Test pitch I have seen” , and lodged an official complaint to the Indian Board about the state of the pitch. It has to be noted that West Indies spinner Clyde Butts failed to take a wicket in 45 overs. Only Patrick Patterson, nought not out in both innings escaped Hirwani’s talons. Five of the dismissals were stumpings by wicketkeeper Kiran More, whose counterpart, Dujon suffered the humiliation twice. In the West Indies second innings only Test debutant Phil Simmons (14), Logie (67), and Butts (38) got to double figures.

The pitch aside, Hirwani’s wizardry of guile and deception cannot be forgotten. Once again, the West Indies Achilles Heel had been exposed.

Aftermath

Hirwani played only 17 Tests in eight years, failing to reproduce the magic of his debut. However, he did add his name to the record books again, bowling 59 consecutive overs during a Test match versus England at the Oval in 1990. When he retired from first-class cricket in 2006, his tally read 732 wickets.

Summary of the five times the West Indies succumbed to the wily foxes of the leg-spin trade.

Fifth Test versus Australia, at Sydney, 1984/85 – (Second) Lost by an innings and 55 runs

Bowlers Bob Holland and Murray Bennett -15 wickets

First Test versus Pakistan , at Faisalabad, 1986/87 – (Third) Lost by 196 runs

Abdul Qadir 6 for 16, as WI dismissed for 53 in the second innings

Fourth Test versus India, at Madras, 1987/88 – (Fifth) Lost by 255 runs – Hirwani 16 for 136

Fourth Test versus Australia, at Sydney, 1988/89 – (Seventh) Australia won by seven wickets

Allan Border 11 for 96

Second Test versus Australia, Melbourne, 1992/93 – (Thirteenth) Australia won by 139 runs

Shane Warne 7 for 52 in the second innings