Authors: Anil Persaud (persaudk@gmail.com) and Aryama (aryama@hotmail.com) were trained in history and political science, respectively, at the Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Authors: Anil Persaud (persaudk@gmail.com) and Aryama (aryama@hotmail.com) were trained in history and political science, respectively, at the Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Part One

1838 was the year when Indians from the East Indies – those Indians whom Columbus set out to meet in 1492 – landed for the very first time in the ‘New World’ on the banks of the river Berbice. One hundred and sixty four disembarked. The date was 5th May, it was a Saturday. Between the short passage from यू० पी (U.P.) and the long journey from Southern Africa, somewhere between reproach and celebration, falls the undeniable significance of that moment on the muddy shores of today’s Guyana. In becoming new, this world, its blood and smoke, would also continue, once again, to become old. Many such journeys would follow, amid similar and changing circumstances and contexts – Trinidad and Jamaica in 1845, Suriname in 1873, the Komagata Maru off the coast of British Columbia, Canada in 1914, to mention a few – but this landing, at Highbury, Berbice on that day came at the end of a journey that closed a 346 year old circle in time. In both instances, 1492 and 1838, the ‘Indians’ were about to get the short end of the colonial stick.

The Legacies of British Slavery project, University College London, has revealed that in the years leading up to 1838 the total number of enslaved Africans at Highbury was 439 and that their enslavers received ‘compensation’ to the tune of £18,555 (approximately £2,631,811 today) from the British Government, at the end of enslavement in their empire in 1833. Highbury began its career as a plantation during the period of Dutch colonization in Berbice as the coffee and sugar plantations St. Jan and Dankbaarheid, respectively. The two were united to form Highbury estate sometime after 1814 when the Dutch transferred the colony to the British. Such is the legacy of Church and State complicity that it remains unclear whether St. Jan refers to Saint John the Baptist or the Dutch slaver St. Jan, shipwrecked on the Reef of Rocus in 1659. The arrival of Indians at Highbury in 1838, therefore, was the continuation of a much older story; the merging of plots, so to speak.

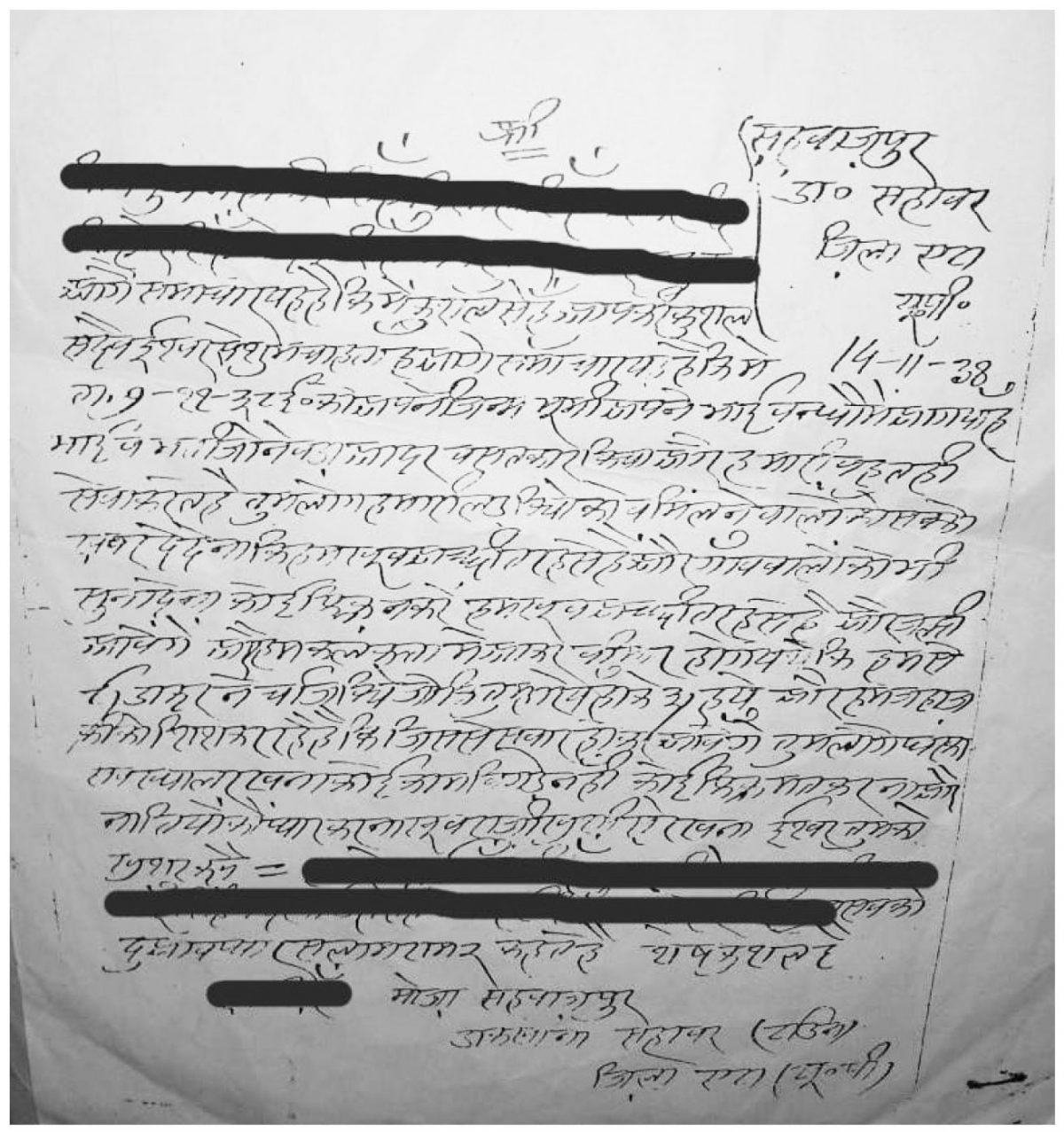

One hundred years later, however, a letter arrived by mail, dated 14th November 1938, from a town named Etah in U.P., to an address in the village and erstwhile plantation of Golden Fleece, Berbice, British Guiana:

The letter and journey: a beginning

What would have been unimaginable in 1838 – an indentured letter from or to Highbury – by 1938 had become rare: such also is the measure of progress. It’s author, who we will refer to as DS, after what would have been several decades’ absence, had just 5 days previously returned to his ‘birthplace’ – मैं तारीख ९/११/३८ ईस को अपने जिन्म भूमी अपने भाई वन्धुओं में आ गया हूँ (On 9/11/38 I came to my birthplace among my brothers and brethren). It was a reunion. But then again, so too was 1838.

DS’s is an 1838 letter in other ways also. Addressed to his children, grandchildren, and fellow villagers in Golden Fleece, his 1938 letter is replete with reassurances that he is well (हम खूब अच्छी तरह से हैं), and that they should not worry (कोई फ़िक्र न करैं). It could have been written from Highbury or Etah in 1838, the only difference being that the reassurances from a century ago would have been false. Works such as Maharani’s Misery by Verene Shepherd, Lisa A . Lindsay et al’s “Rebecca’s Ordeal, from Africa to the Caribbean: Sexual Exploitation, Freedom Struggles, and Black Atlantic Biography,” and Anil Persaud’s “Transformed over Seas: ‘Medical Comforts’ aboard Nineteenth Emigrant Ships,” touch on various currents associated with forced displacement across the Atlantic and Indian oceans. DS’s reassurances, however, were not only the result of the intergenerational memory of earlier transatlantic-Indian ocean death and illness.

In what was yet another instance of the relentlessness of history, DS’s wife died while he was on board yet still in port at Demerara preparing to depart. As per family history, he was able disembark and attend her funeral before finally setting sail on what we can infer was for him a significant journey of return. With this knowledge in mind, the meaning of his salutations is tinged with the added burden of a family in grief: हमारी लड़कियों को […] खबर दे देना की हम खूब अच्छी तरह से हैं (Tell our girls that I am doing well).

Upon arrival in Calcutta (Kolkata since 2001), and before his onward journey to Etah, his ‘land of birth’ (जिन्म भूमी), DS fell ill. हम कलकत्ता में आकर बीमार हो गए थे की हम से £2 डॉक्टर ने चार्ज किये जो तुम्हारे यहाँ के ३[?] हुए. He was treated by a doctor and charged £2. This time around, health insurance was not included in the price of the trip; such also is progress. He writes that the £2 he paid was equivalent to 3 units of the currency in ‘your place,’ meaning British Guiana in 1938, (the symbol for that currency is unclear in the letter). The history of currency in Guyana is yet to be written.

As the words in his letter reveal, it was written from a place with an entangled history of intertwined dialects and languages – Brijbhasa, Awadhi, Khari Boli and Bhojpuri – that formed the basis of what would later become modern Hindi. Furthermore, words such as खत (Urdu meaning ‘letter’) and कुशल (Hindi meaning ‘well’), for instance, suggest that Hindustani, as a lingua franca, was in practice in British Guiana as it was in U.P. As such, DS’s letter is also a map for the ear and tongue, one that allows us to eavesdrop on conversations between languages – for instance, Hindi, Urdu, English and Hindustani. Behind what has come to be recognized as ‘Bhojpuri’ in Guyana, therefore, and underneath the wave of migrations, lies histories of regions, languages, cultures and traditions that overlap but which are also in conflict and competition with each other: Bhojpuri is a letter in an alphabet of languages.

As happy as he was to be with his family in his birthplace, and as grateful as he was for the welcome he received – भाई- भतीजे ने बड़ा आदर सत्कार किया वगैरह भाई बहुत ही सेवा करते हैं (I was received with respect and hospitality by my brother and nephews, etcetera, brother is taking care of me), DS was anxious. To हम खूब अच्छी तरह से हैं (I am doing very well), he immediately added: और जल्दी आवेंगे (and I will return soon). He goes on to inform them that: हम जहाज की कोशिश कर रहे हैं की जिससे सवार होकर आवेंगे (I am trying to board the ship to come back). In sum, though physically in his jinm bhoomi and being warmly welcomed by relatives, after what would have been weeks at sea, DS was, within five days of arriving, already making arrangements for his return journey. Until then, he wrote, तुम लोग घर का सब का ख्याल रखना कोई काम बिगरे नहीं (You all take care of each other at home and ensure that nothing goes wrong). As for the जिन्म भूमी, homeland, type of nationalism that was rearing its head at the four corners of the earth, DS’s letter evinced not the slightest interest.

In many ways, therefore, DS’s is as much a letter of 1838 as it is of 1938. Until it is not. It is also unlike other letters.

For example, DS’s letter is not like the 1963 letter from Birmingham jail by Martin Luther King Jr., or Martin Luther’s letter to Pope Leo X in 1520. It is not Samuel Butler’s letter from New Zealand in 1863, “Darwin among the Machines.” It is not the 1939 Einstein-Szilard letter to the 32nd President of the United States of America, Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning, on the heels of the German discovery of fission in December 1938, of the potential development of an atomic bomb by the Nazis. Nor is it M.K. Gandhi’s undelivered 1939 letter to Adolph Hitler. Neither is it any of Bechu’s letters to the Editors of various local British Guiana newspapers between 1896 and 1901, The Daily Chronicle and The Argosy for example.

Its difference, from the above sample of ‘letters that changed the world’, makes DS’s letter very common and easy to overlook. It could have been written by anyone who undertook a journey and was writing to inform his folks at home that he arrived safely, was well and well received, that his hosts send their regards, and that he was making arrangements for his return, in the meantime they should take care of the home and each other. That is the substance of DS’s 1838 letter.

A world at the crossroads?

Whether DS was paying attention or not, in 1938 nationalist tides were swelling around the globe: in Europe, in the East, as well as in the West Indies. Hitler, as Aimé Césaire explained, was about to apply in Europe “des procédés colonialistes dont ne relevaient jusqu’ici que les Arabes d’Algérie, les coolies de l’Inde et les nègres d’Afrique” (“colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively for the Arabs of Algeria, the ‘coolies’ of India and the ‘blacks’ of Africa”) – and call it World War II. The partitioners were re-sharpening their knives. The night of 9-10 November 1938, the night DS arrived at his ‘land of birth,’ his जिन्म भूमी, is also known to history as the ‘Night of Broken Glass’ (Kristallnacht in German, literally ‘Crystal Night’) when Nazis littered streets with the broken glass from the “windows of Jewish-owned stores, buildings and synagogues.” 9th November was also the day that one British committee, the Woodhead Commission, rejected the plan of another British committee, the Peel Commission, for the partition of Mandatory Palestine on the grounds that it could not be achieved without a large forced transfer of Arabs. The final act of colonial oppression presents as a dramatis personae of competing committees.

Neither is there any indication in his letter that DS was aware that the place where he was staying, Etah, was in the province where the overwhelming number of recent Hindu-Muslim riots had taken place. Maybe he did not wish to alarm the folks back home by including mention of it. As one, near contemporaneous account put it, however: between 1936 and 1938, 113 of the 116 Hindu-Muslim riots “are recorded in the police statistics for this one province alone.” The province being referred to is the United Provinces, in which Etah is a town and which became Uttar Pradesh in 1950. During the indenture period and in 1938 when DS was visiting, neither Uttar Pradesh nor India, as we know them, existed.

To be continued…

— Appeal: Rare though it may be, the authors have not assumed that DS’s letter is unique. If readers are aware of any similar letter, postcard, telegram, or any other communication exchanged between Guyana and its other worlds, kindly let us know so that we may together continue to do the work of arresting the silences between continents and peoples before they progress into irreversible deafness.