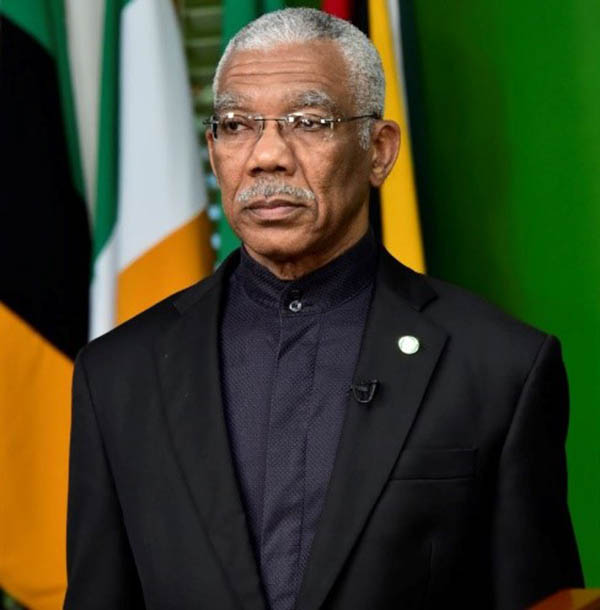

Though finding that Justice Navindra Singh had “wrongfully” exercised his discretion to waive a pre-trial review (PTR) in the libel case which former President David Granger brought against several media houses, the Full Court last month ruled that it is that judge who is to conduct the trial, since it was he who had also conducted the case management conference (CMC).

Granger, is however, appealing this latter finding of the Full Court, strongly objecting to Justice Singh presiding over his trial because; as he argues, Justice Singh exercised powers of a pre-trial review judge.

In his motion seeking special leave to appeal to the Court of Appeal, Granger is contending that the Full Court judges got it wrong and that that aspect of their decision is “bad in law.”

Back in April of last year, Granger, through his attorney Roysdale Forde SC, had written to Justice Singh voicing displeasure with him conducting a pre-trial review (PTR) and also presiding over the trial of his $2.6 billion libel suit.

It had been Granger’s contention that upon a proper construction of Part 38 (5) of the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR), the pre-trial judge is not to be the case management judge or the judge presiding over the trial.

Challenging the waiver, Forde had argued that in breach of the Rules, Justice Singh made two determinations without the consent of the parties: (1) that he will be the PTR judge and (2) that he will also be the trial judge.

Justices Damone Younge and Gino Persaud who heard the appeal in the Full Court declared, however, that after examining the record of the proceedings and carefully considering the CPR as it relates to PTRs, the Court found that contrary to Granger’s contention, the hearing conducted by Justice Singh “was a continuation of the CMC and not a PTR.”

Citing Part 25:04 (4) of the CPR which falls under the provisions dealing with the CMC (Fixing and Variation of Timelines) at the first CMC and Part 25:03 – Case Management Conference; Forde had argued that Justice Singh at that first CMC made a determination that it was necessary that there be a PTR.

The lawyer had then submitted, that with the CMC having then ended, the PTR stage commenced; arguing that a proper construction of Part 38 (5) of the CPR, reveals the fundamental position that the pre-trial judge is not to be the case management judge or the presiding judge at the trial.

The Full Court judges had said in their ruling that having examined the directives which had been given to the parties by Justice Singh, the hearing which the Appellant contended to have been a PTR “was in actual fact a continuation of the CMC.”

Those directives the Court said, continued and followed the timetable which was set at the first CMC of the steps to be taken in the proceeding before the matter reaches the trial stage as required under Part 25 of the CPR.

“This Court is fortified in its view that the hearing conducted on the 28th April 2022 was a CMC and not a PTR as argued by the Appellant” the two judges declared.

They went on to say that in the first place, the objective of the PTR is “to encourage a settlement prior to trial, assist in identifying or narrowing the actual issues for trial, and deal with any outstanding issues before trial.”

The judges said that none of those objectives could have been realized on April 28th as is being contended by Granger; since there were still evidential objections and interrogatories to be addressed and a supplemental affidavit of witness statement to be filed.

They ruled that for those reasons, Granger’s contention that Justice Singh conducted the PTR which was continued on an adjourned date, could not be sustained.

Regarding the waiver of the PTR, the Full Court justices noted that Rule 38.01(6) gives the Court a very wide discretion to waive the PTR at any time and on its own initiative; but cautioned that where a litigant withholds consent under R. 38.01(5), this ought to be taken into account by a CMC judge when deciding whether or not to waive the PTR.

The appellate tribunal did point out, however, that it would be apposite to note that the provisions of Rule 38.01(5) apply only “where practicable” and is not absolute and unqualified as the submissions of the Appellant suggested.

Against this background the Full Court said it was of the view that Rule 38.01(5) envisages that the CMC judge can be the judge who conducts the PTR where it is impractical for one judge to conduct CMC/Trial and another to conduct the PTR.

On that point the judges then highlighted in their ruling that there was nothing in the record of the proceedings which gave any indication that there were circumstances which made it impractical for a different judge to conduct the PTR; “so that the exercise of the judge’s discretion to waive PTR, without more, appears to be against the spirit of the CPR particularly when one considers that it came after His Honour was made aware that the Appellant was withholding his consent as he is entitled to do under Rule 38.01 (5).”

The judges were quick to point out, however, that the entitlement of a litigant to withhold consent is confined to the CMC or trial judge also being the PTR judge; adding that in their view, it is not within the contemplation of the Rules, that a litigant can withhold consent to the CMC judge being the trial judge.

“This would encourage judge shopping which cannot be countenanced. The learned trial judge, being the CMC judge, must ultimately be the judge to conduct the trial,” Justice Younge and Persaud declared.

They then went on to further declare that any judge who conducts a CMC is in command of the pleaded case, the facts traversed, discovery, the evidence by way of witness statements with exhibits attached and the full panoply of powers that the CMC envisages.

“It is therefore logical and follows common sense that a CMC judge is always best placed to conduct the trial and this, as far as we are aware, is the status quo following the implementation of the CPR. To argue that a judge other than the CMC judge must conduct the trial is neither prudent nor practicable. This is so particularly when one considers that the resources of the Supreme Court are severely limited. There is nothing in this appeal to persuade this Court to depart from this norm,” the Full Court judges said.

In the final analysis they ruled that the hearing conducted by Justice Singh on April 28th April last year was a continuation of the CMC and not a PTR.

They would, however, go on to hold that while Justice Singh has the power to waive a PTR at any time, given the circumstances of the case and in view of the fact that there was no consent by the Appellant, “the exercise of his discretion to waive the PTR was wrongfully exercised.”

The judges said that in the face of Granger withholding his consent, it was not open to the trial judge to counter that by waiving the PTR. They said that at that point, the objection should have been noted and the matter referred to the Chief Justice for assignment to a different judge to conduct the PTR, after which the matter would return to Justice Singh for trial.

In all the circumstances, the Full Court allowed Granger’s appeal regarding the waiver; but ordered that the matter be referred to the Chief Justice to assign a different judge to conduct the PTR; at the conclusion of which the matter is to be remitted to Justice Singh for trial.

In his motion, however, seeking special leave of the Court of Appeal to challenge Justices Younge and Persaud’s ruling that Justice Singh conducts his trial, Granger is contending that the Full Court judges got it wrong and that that aspect of their decision is “bad in law.”

He argues that the judges erred in law when they concluded that the matter was “ostensibly” fixed for pre-trial review on the 13th day of June, 2022. According to Granger, the fact was that the matter was fixed for pre-trial review.

The former president is of the view that because of this, the Full Court could not then go on to hold that the matter be remitted to Justice Singh for trial.

He submits in his motion that the Full Court by its decision that the matter be referred to the Chief Justice for a judge to be assigned to conduct a pre-trial review, “is of itself a concession” that Justice Singh did in fact exercise powers of a pre-trial judge.

Against this background, Granger has said that his appeal has merit and is likely to succeed. He further says that for those reasons he should be allowed to mount his challenge, as if rejected, “I would suffer a grave injustice, I having no other recourse or refuge.”

Granger’s $2.6 billion lawsuit is against dailies—Stabroek News, Kaieteur News and the Guyana Times, which he says have all besmirched his character through letters published by communications specialist Christopher ‘Kit’ Nascimento.

In the action, Granger said that Nascimento accuses him of attempting to defy the will of the people in the March 2nd, 2020 Elections.