CAMPINAS, Brazil, (Reuters) – Brazil is taking extra precautions to protect the world’s largest poultry export industry from a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus that was this week detected among wild birds in the country after previously hitting neighboring nations.

Nearly $10 billion of chicken exports would be at risk if H5N1 bird flu infects commercial flocks in Brazil, which has taken on a growing role in supplying the world’s poultry and eggs as importing nations ban chicken and turkey meat from countries with the virus.

On Monday, the only World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) accredited lab in Latin America confirmed detection of H5N1 in two wild Thalasseus acuflavidus birds, or Cabot’s terns, and one Brown Booby (Sula leucogaster) captured in Espirito Santo state.

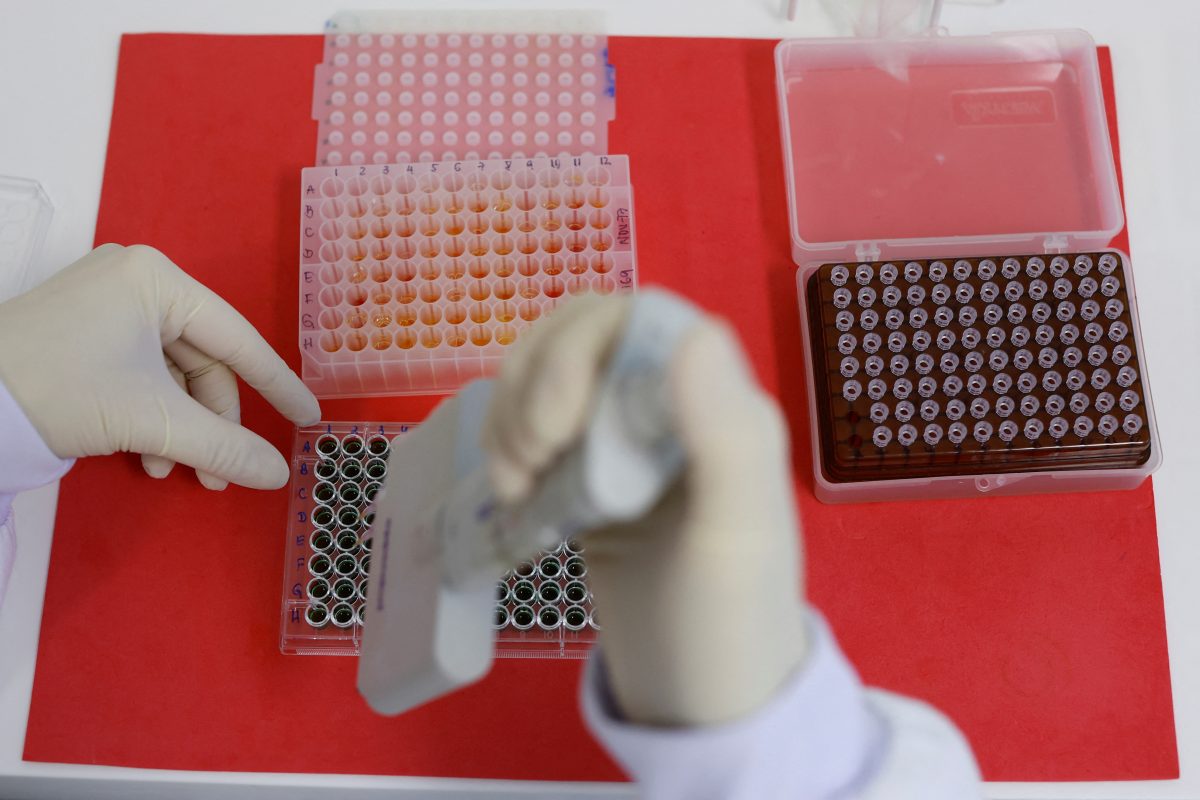

Per protocol, local veterinarians in Espirito Santo took samples from the birds on site and sent them to the reference lab in Campinas, Brazil.

“The entire industry is mobilized to monitor the situation identified in Espirito Santo,” national meat lobby ABPA said in a statement.

A case of bird flu on a farm usually results in the entire flock being killed and can trigger trade restrictions from importing countries, while detection among wild birds does not spark bans under WOAH guidelines.

Brazilian officials say they do not expect the cases in wild birds to have any trade impact, and noted Espirito Santo on Brazil’s central Atlantic coast does not border any of the country’s main poultry producing states in the far south.

In other countries, avian flu outbreaks in wild birds have frequently been followed by transmission to commercial flocks.

Bird flu outbreaks have contributed to higher prices of poultry and eggs, normally an affordable source of protein.

The Brazilian government this year raised investments 19-fold to increase testing capacity at its network of six federal laboratories, and increased the overall budget of its Animal and Plant Health and Inspection Services by some 12% to 209 million reais ($42 million).

“For every 1 real spent in the Campinas federal laboratory, some 64 reais of potential losses are avoided to the meat industry,” said Rodrigo Nazareno, who coordinates the national laboratory network.

Reuters visited WOAH’s reference lab on April 25, before this week’s positive test. Lab workers were already on high alert after more than 75 outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza were reported in nine countries in Central and South America, many for the first time ever.

As poultry farmers increased monitoring, Brazil saw a six-fold increase in suspect case notifications through early May.

Brazil in recent weeks started using drones to patrol sensitive areas such as the Pantanal, the world’s largest freshwater wetland, and implemented a strict ban on commercial farm visits by non-authorized persons.

After cases were confirmed in neighboring Argentina and Uruguay, Brazil announced in late March a 90-day suspension of all events involving the exposition of poultry.

The agriculture ministry told Reuters that more testing may be required within a 10-km (6.2-mile) radius of the Espirito Santo outbreaks, including of commercial flocks, and that it will maintain surveillance of potential cases in wild birds nationwide.

Brazil’s chicken export revenue jumped by more than 27% in dollars last year as local companies benefited from the global avian flu scare, which opened up new markets.

China and the Middle East remained big customers. And the European Union, where countries like France had to kill millions of birds to contain outbreaks, boosted import volumes from Brazil by some 23%, industry data show.

Since early 2022, wild birds have spread the highly infectious virus farther and wider around the world than ever before. While humans can contract H5N1, such cases remain rare, and global health officials have said the risk to humans is low.

The virus arrived in South America through migratory birds, said Masaio Mizuno Ishizuka, a senior epidemiologist at the University of Sao Paulo.

Normally birds will only spread bird flu for around five days. But the virus’ presence in small sea life the birds feed on may have enabled its broader spread this year, she said.

“The virus is extremely capable of presenting mutations to increase its potential for survival as a species,” Ishizuka cautioned.