Authors: Anil Persaud (persaudk@gmail.com) and Aryama (aryama@hotmail.com) were trained in history and political science, respectively, at the Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Part Two

The world DS found himself in 1938 was tumultuous for reasons not restricted to communal riots with which we ended Part One’s diaspora column last week.

Not every agitation is a riot; some are also strikes. For instance, in November 1938 itself, had DS’s ship sailed through the Suez Canal and docked at Bombay, rather than at Calcutta, he may have found cause to pause. As the historian, Santosh Suradkar, in “The Labour Act of 1938,” notes: “the strike of [7] November 1938 was the first time that the untouchable workers, organised under the Independent Labour Party (ILP) led by B R Ambedkar, and the communists, came together to strike.”

St. Lucian economist and Nobel laureate Arthur Lewis documented this pivotal period in West Indian labour history in his 1939 book, Labour in the West Indies: The Birth of a Workers’ Movement. Citing Lewis, Eric Williams in From Columbus to Castro: The History of the Caribbean, 1492–1969, declared: “The revolution broke out in the years 1935-1938.” In his Worker’s Age, March 1938 article titled, “British Imperialism in the West Indies,” George Padmore explained why: “West Indian workers, Negroes as well as East Indians, are among the worst paid labourers in the world and, in consequence, their standard of living is extremely low.”

In retrospect then, the line, “things fall apart; the centre cannot hold,” when read in 1938, described a world very much looking backwards to the Irish poet, William Butler Yeats and forwards to the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe. Those seven words, lurking as they were at the intersection of past poetry and future prose, flowed from the open veins of yet another decrepit empire, as immortalized in Yeat’s 1920 poem, “The Second Coming”:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Achebe, in his 1959 novel, Things Fall Apart, would express similar concerns differently:

And now the rains had really come, so heavy and persistent that even the village rain-maker no longer claimed to be able to intervene. He could not stop the rain now, just as he would not attempt to start it in the heart of the dry season, without serious danger to his own health. The personal dynamism required to counter the forces of these extremes of weather would be far too great for the human frame.

Guyana and the West Indies in 1938, like the rest of the world, were at a crossroads, and, so was DS and the letter he sent.

Commencement of a journey and the end of the letter

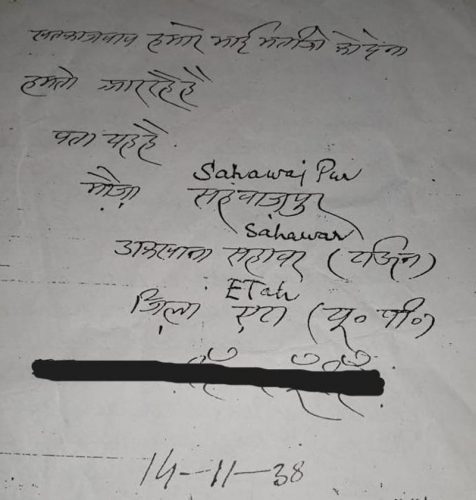

Before leaving Etah, DS mailed his letter. In it he specified a return address in Etah. He instructed his children that should they need to they could send a reply to his brother and nephews, खत का जबाब हमारे भाई भतीजे को देना, at the address given below.

Figure 3: DS’s letter, return address in Etah, U.P.

Between the arrival and the departure, though, falls the journey. Between the longing and the belonging, between the person and the place, between the जिन्म (birth) and the भूमी (earth), falls the journey.

From Etah, DS may have traveled first to Allahabad (Prayagraj since 2018). From there he may have boarded a train for Howrah railway station, Calcutta, on the bank of the Hooghli. From Howrah he may have had to make his way to the Khidderpore Depot along Garden Reach Road, as he would have on his first journey to British Guiana. The Hooghly, also called the Bhagirathi river, snakes north to merge with the Ganges and south into the Bay of Bengal. Once in the Indian Ocean proper, maybe a stop at Mauritius, or St. Helena. But maybe not in 1938. After that it was nonstop around the Cape of Good Hope, where the currents of the Indian and Atlantic oceans meet, across the Atlantic to dock once more at the Port of Demerara.

Translating experiences and the language of dialect

Between खत का जबाब हमारे भाई भतीजे को देना (Send the reply to my brother and nephews) and पता ये है (the address is), DS inserted the line: हम तो आर रहै हैं (meaning ‘I am,’ but literally ‘we are,’ coming).

That line, however, contains his letter’s only spelling mistake. Instead of हम तो आरहै हैं, DS wrote, हम तो आररहै हैं. And, because आर is rarely a word in itself – one instance of when it is, but not quite, is, आर-पार, which means fittingly ‘across’ – it initially featured in our translation as चार. The style in which he writes letter अ, is rarely used anymore and can appear to today’s reader as च: see the manner in which he writes the words आगे (ahead)/अच्छी (good) and चार्ज (charge)/समाचार (news). Along the way हम तो आररहै हैं (which is meaningless) became the confusing हम तो चाररहै हैं (‘we are four pathways’) which in turn tentatively became the enigmatic हम तो चौराहे हैं (‘we are at a crossroads’), until finally, it resolved back into the simple हम तो आरहै हैं (I am coming). A letter, both of the alphabet but also of the epistolary kind, can make the world of difference.

Before the translation conundrum that this line invited could be fully resolved, however, there was one further complication that needed to be addressed: the subject हम. The हम/मैं (we/I) debate, as it is known in the vernacular, though of relative recent origin, is already locally exhausted. DS’s letter, nonetheless, must be read where it was written: at the intersection of that local debate and the larger colonial effort to subjugate already and stubbornly modern senses, meanings and identities of collectives and communities temporarily trapped in mercantilist oriented orbits. DS addresses this world also, हम खूब अच्छी तरह से हैं और गांव वालों को भी सुना देना (I am very well, tell the villagers [of Golden Fleece] too). In the common parlance of today, therefore, the repetition of हम in DS’s letter echoes a pushback of the collective we against the individual I by insisting not only on their overlap but on their merger as well. The great displacement of which DS was a part, therefore, applied not only to labouring bodies, it reached in further to displace the plural we in favour of the singular I.

हम तो आरहै हैं (I am coming): let there be no doubt, when DS writes that he is coming, he means it. In the middle of a crossroads, where the potential for paralysis is greatest, DS says with utmost calm and decisiveness, हम तो आरहै हैं (I am coming). Among the possible figures who speak directly, in situ and with comparable composure to this relationship between the individual, the collective and the crossroads, one comes to mind; Bob Marley and the Wailers “Ride Natty Ride”:

Dready got a job to do

And he’s got to fulfill that mission

To see his hurt is their greatest ambition, yeah!

But we will survive in this world of competition

‘Cause no matter what they do

Natty keep on comin’ through

And no matter what they say

Natty do them every day, yeah!

Natty dread rides again

Through the mystics of tomorrow

Natty dread rides again

Have no fear, have no sorrow, yeah!

In parts of this world, tracts, treaties and even treatises are still recorded in song; in others, not even. Though unscripted, if we place an ear close enough to the speaker, we might just hear Natty saying – as she rides through the fire, the illusion and the confusion, through the storm and the calm – ‘I am coming,’ and we would be mistaken. Because what she would actually be saying is I&I coming. Calling attention to two ‘I’s forging a collective we, on the one hand, and the multitude in हम struggling against the hegemony of any particular I, on the other. In DS and Natty, therefore, two epic figures (of speech) meet: हम and I&I, both grappling with the perennial political problem of ‘I or we’ versus ‘I and we.’

आगे समाचार यह है की (Further news is that…)

Like songs and poems, phrases such as ‘आगे समाचार यह है की,’ with which DS began his letter belong to the idioms people use to translate their subjective experiences into communicable expressions. Similarly, there are customary endings.

DS ended his letter to his folks in Golden Fleece – family and villagers – with a note informing them that his brother, nephews and brethren in Etah, requested that, separated by oceans and continents, he convey the following greeting to them: दुआ प्यार सलाम राम2 कहते हैं, dua (supplication), pyar (love), salam, Ram2. Such was the greeting chosen to shrink the distance not only between old and new worlds but also between the empires and hamlets of history through which DS and readers of his letter are still forced to pass. The absence of spaces between words in DS’s handwritten letter takes on additional significance in this greeting, one word running into the other as they are, दुआप्यारसलामराम2, duapyarsalamram2, creating in the process a now unusual intimacy between Ram and salam. And there is more. The spoken Ram-Ram becomes the written, economical Ram2, and out of the written salam echoes of multiple salams can be heard. The salam of the Arabic greeting السلام علیکم (सलाम अलैकुम, salam alaykum (‘peace be upon you’) and its response السلام وعليكم, wa ʿalaykumu s-salam (‘and peace be upon you’), common to Muslims along with some Christians and Jews. But also the salam of लाल सलाम, lal salam, Red Salute, a greeting common among communists in South Asia, such as those gathered in Bombay that November. This entangled greeting would not survive another decade; the invisible spaces between words in DS’s letter would grow into a chasm between people. But not yet. In 1938, the Ram of Ram2 had not yet become the Ram of the राम जन्मभूमि (Ram janmabhoomi, the birthplace of Ram) movement.

As Robert Johnson put it in “Cross Road Blues” (1937), the Lord was attending to another kind of plea:

And I went to the crossroad, mama, I looked east and west

I went to the crossroad, baby, I looked east and west

Lord, I didn’t have no sweet woman

Oh well, babe, in my distress.

At this four way intersection of intercontinental greetings then – dua, pyar, salam, Ram2 – DS’s letter, an otherwise smorgasbord of formalities, rises suddenly and boldly, as if, but not quite, out of nowhere, to offer a fleeting glimpse of a vanishing sublime, where for a moment all partings were not partitions, all movements were not migrations and what was coming need not have come.

—

Appeal: Rare though it may be, the authors have not assumed that DS’s letter is unique. If readers are aware of any similar letter, postcard, telegram, or any other communication exchanged between Guyana and its other worlds, kindly let us know so that we may together continue to do the work of arresting the silences between continents and peoples before they progress into irreversible deafness.